I’ve just been at a three-day seminar at the Institute for Government, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, to help academics learn how to influence public policy. The seminar brought together 15 academics in disciplines ranging from literary criticism to design and urban planning.The IFG arranged an impressive line-up of Westminster big-wigs to talk to us, including Matthew Taylor of the RSA, Gareth Davies of the civil service, and Sir Gus O’Donnell, former head of the civil service. They gave us a fascinating look into how politics works, but also showed how hard it is for academics to influence policy.

I’ve just been at a three-day seminar at the Institute for Government, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council, to help academics learn how to influence public policy. The seminar brought together 15 academics in disciplines ranging from literary criticism to design and urban planning.The IFG arranged an impressive line-up of Westminster big-wigs to talk to us, including Matthew Taylor of the RSA, Gareth Davies of the civil service, and Sir Gus O’Donnell, former head of the civil service. They gave us a fascinating look into how politics works, but also showed how hard it is for academics to influence policy.

As one civil servant told us, ministers are extremely busy and rarely get time to read a newspaper article, let alone a research paper. They want any ‘action points’ to be clearly expressed in a two-page document. Tony Blair apparently said that if you can’t express your idea in two sentences, you don’t understand it. All of this was quite off-putting for some of the academics, trained as they are to appreciate subtlety, nuance and multiple readings. One academic was particularly horrified by the idea of using an infograph to get their ideas across.

On their side, some policy-makers expressed frustration at how little useful advice they were getting for all the money they were putting into academic research. For example, the government somewhat controversially set aside a pot of money for academic research into the ‘Big Society’, but apparently, few practical recommendations have arisen from all that research. I think that shows a mistake in timing – there is a lag between ‘government time’ and ‘academic time’, and academics can best influence policy in the quieter years before government, when politicians are formulating their broader policy visions, rather than during government when any academic contributions risk being seen as entirely expedient.

Another policy-maker noted that American academics seemed to be better at influencing British policy than domestic thinkers: think of the ‘Nudge unit’ inspired by Richard Thaler, Cass Sunstein and Daniel Kahneman; or the impact of Martin Seligman’s Positive Psychology on British policy. Why is the RSA’s schedule of public talks so full of visiting American intellectuals, with so few British intellectuals? Perhaps, one speaker speculated, American academics are better at selling themselves because they have a much bigger book market to sell into. That emphasis on mass communication makes them better able to deliver TED-style pitches to busy policy-makers.

However, it’s still the case in the US that arts and humanities scholars have little influence on public policy, with a few notable exceptions in history, law and ethics (Michael Sandel, Martha Nussbaum). English literature and cultural studies have little influence on policy, and perhaps that’s as it should be – novels and poetry thankfully resist the utilitarian bent of our times.

To be provocative: is it possible that the huge influence of critical theory, and particularly of Michel Foucault, on arts and humanities academics have, ironically, rendered them less capable of influencing power and changing the world? Doing an arts and humanities PhD sometimes reminds me of initiation into a cult – you go through a three-year period of social isolation, by the end of which you emerge fully inculcated in the radical doctrine of critical theory. This world-view puts you at odds not just with public policy, but also with mass society, including your friends, family and lovers. One academic told me that few relationships survive a humanities PhD, and that she herself had broken up with her boyfriend half-way through her studies (she’s now happily married to a Lacanian). The initiate in critical theory can end up so sceptical of power, they become incapable of influencing it. This limits their influence to the ‘in-culture’ of academia – a culture which is ironically very hierarchical. I say this as an ‘outsider’ – someone without a PhD who came into academia through journalism (so perhaps I’m just insecure about my lack of qualifications!)

Four ways that arts and humanities influence public policy

Let me end on four positive ways that arts and humanities research can and do influence public policy. Firstly, through investigating stories and their impact on our emotions. The arts and humanities are right at the centre of public policy because political communication is to a large extent about stories, words, symbols and how they move us. The scop, the bard, the story-weaver, has always been an important part of court politics. The most obvious way that the arts and humanities could influence public policy, then, is through the exploration of rhetoric, narrative and its effect on the emotions. This exploration would include the recent work of social scientists and psychologists like Jonathan Haidt and George Lakoff into values and metaphor and how they move us.

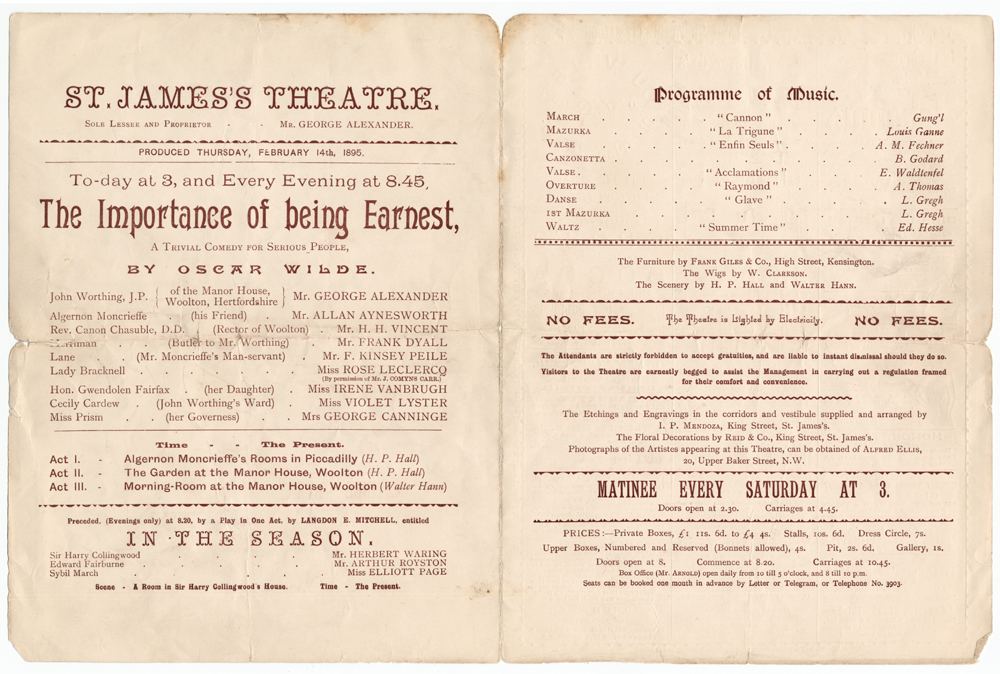

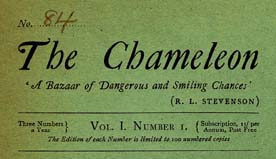

At the moment, as far as I’m aware, there is only one centre for the study of rhetoric in the UK, which was opened in Royal Holloway’s classics department in 2010 – though I note that Philip Gould left money in his will for a ‘visiting professorship in rhetoric and the art of public persuasion’ at Oxford. There’s room for much more research in this area, and it would have the benefit of being very interesting and (dare I say it ) useful to politicians and their speech-writers. What are Shakespeare’s history plays if not explorations of the rhetoric, narratives and myths of political power? Winston Churchill was able to ‘mobilize the English language and put it to battle’ (as JFK put it) by studying rhetoric, by reading Shakespeare. Our political culture would be greatly improved if more politicians followed his example. Politicians improve or debase our political culture through their language.

Secondly, history has an obvious role to play in public policy. We heard, for example, how the History and Policy project helped the policy-makers working on pension reform in the mid-noughties to unearth the history of the existing pension legislation and see how it had grown anachronistic. History helps us see how aspects of our culture that we might take as natural and eternal are in fact recent and constructed. It also gives us useful historical scenarios to think about where we are and where we’re going (think of Paul Kennedy’s work on imperial over-reach, for example, which might have been usefully read by the Bush government). Sir Adam Roberts is an example of a historian who has frequently contributed memoranda to parliamentary debates.

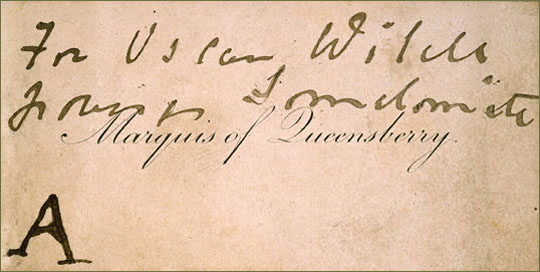

Thirdly, applied ethics has usefully engaged in public policy for several decades, from Baroness Warnock and others’ work on euthanasia, to the contribution of academic philosophers to the Leveson Inquiry’s debate on balancing press freedom with the right to privacy.

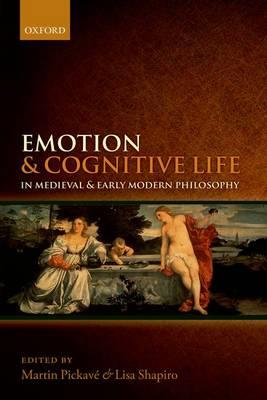

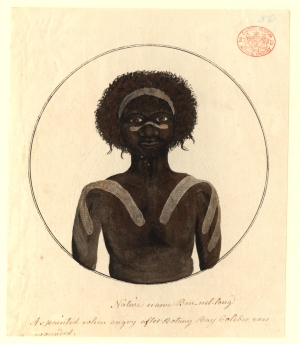

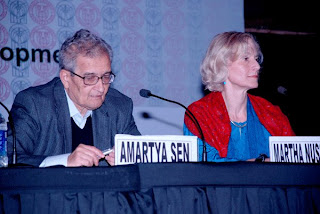

Amartya Sen and Martha Nussbaum: a good example of cooperation between the humanities and social sciences

Finally, arts and humanities scholars have a clear contribution to make to the politics of well-being. This new movement in politics has so far been dominated by economists and psychologists – the Office of National Statistics’ committee to define ‘national well-being’, for example, didn’t contain a single representative from the arts and humanities. Now, well-being economists and psychologists like Richard Layard and Amartya Sen are increasingly engaging with the humanities, particularly with philosophy. They are engaging with the history and plurality of philosophical definitions of well-being. This is good news, as it means well-being policy will become less top-down and dogmatic and more democratic. For example, I hope to work with Layard’s Action for Happiness to design a ‘well-being course’ for adults, which won’t try to shoe-horn everyone into one pre-fabricated definition of well-being, but will instead enable people to consider the scientific evidence, while also debating and forming their own idea of the good life.

At the moment, there are two main Centres for Well-Being in English academia – Richard Layard’s team at the LSE, which is mainly economists; and Felicia Huppert’s Well-Being Institute at Cambridge, which is mainly psychologists. Hopefully we can get the Well-Being Project at Queen Mary started up in earnest this year, to bring thinkers and practitioners from the arts and humanities more into the conversation.