There’ve been plenty of good articles on the history of emotions in the media in the last few weeks, some of which were written by or quoted scholars at the Centre.

In the Telegraph, William Leith asked whatever happened to the British stiff upper lip, and interviewed experts including the BBC’s Adam Curtis and the Centre’s own Thomas Dixon. Leith writes:

The academic historian Thomas Dixon, who has studied the history of crying, tells me that the 18th and 19th centuries were very “tear-soaked” – crying in public, particularly at the theatre, and particularly in the cheap seats, was no big deal. Emoting was linked to popular culture – and also to religion. There used to be lots of weeping when people found God, and when they repented their sins. Then came the era of the “stiff upper lip”, an age of stoicism engendered by Empire, the Victorian public schools, and muscular Christianity.

Ah — the stiff upper lip! Even now, it has a huge resonance. Dixon tells me about a British POW appearing unmoved while being tortured by the Japanese in the Second World War. His captors were amazed. “No Britisher ever cries,” he told them – which makes me want to cry. If you were British, you were supposed to keep your emotions to yourself; it was all part of showing what Dixon describes as your “strength and superiority”. But the stiff upper lip was just a blip in history. The expression, possibly American, and probably coined in the 19th century, refers to a time when men had big moustaches, which would magnify any unseemly lip-quivering.

The fashion for keeping your emotions bottled up lasted about 100 years. “Since the Seventies,” says Dixon, “we’ve been returning to something like normality.” In other words, normality is about losing control.

Another Centre scholar, Lindsey Fitzharris, wrote an excellent feature for the Guardian on the history of public displays of corpses, linking in to the widely circulated images of the last hours of Colonel Gaddadi. She wrote:

The display of one’s enemies after death reaches across cultures and across time. In 1540, Henry VIII granted the Barber-Surgeons Company the annual right to the bodies of four executed criminals. With it, he formally bound the act of the executioner to that of the surgeon: one executed the body, the other executed the law. The association of public dissection with crime and punishment was given further sanction with the passing of the Murder Act in 1751, which mandated that all murderers be dissected after death.

In these cases, as with Gaddafi, there was a desire to humiliate the person in death. This could not be clearer than in William Hogarth’s engravings, The Four Stages of Cruelty (1751). In them, we see the moral demise of the fictional character, Tom Nero, torturing animals as an adolescent and eventually murdering his lover, Ann Gill. In the final scene, Nero is laid out on the surgeon’s dissection table, his innards spilling out onto the floor while a dog eats his intestines. There is nothing dignified about this death.

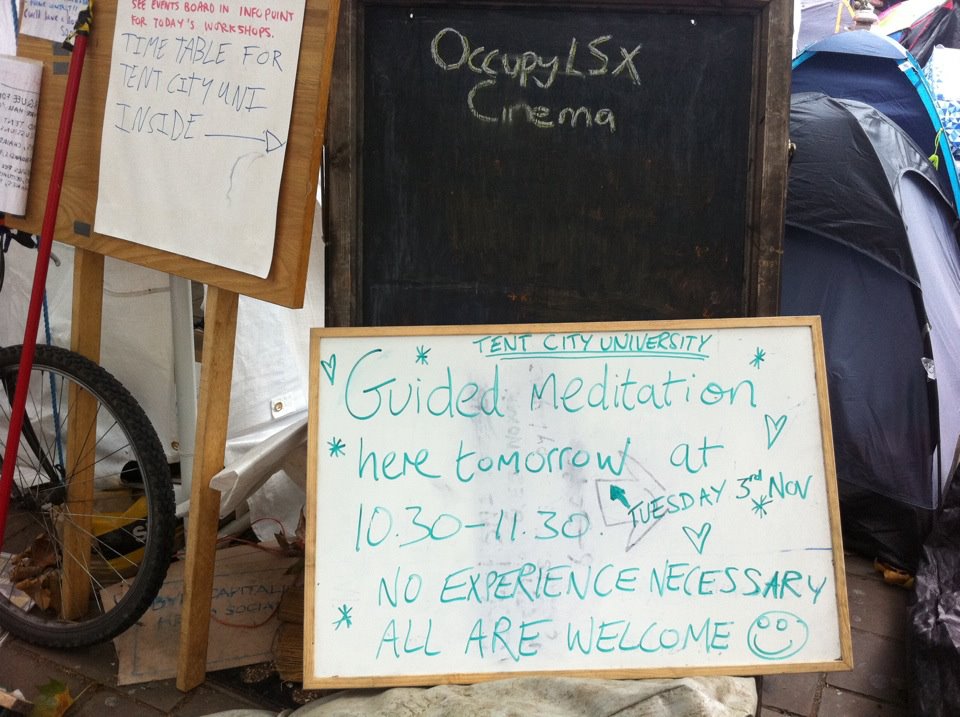

The Centre’s Jules Evans posted an interview with Kalle Lasn, the 70-year-old trouble-maker who set up Adbusters, which in turn came up with the idea to Occupy Wall Street. The interview, from Jules’ blog, was picked up by The New Republic and the New York Times blogs. Kalle told Jules about his background in advertizing, and his expectation of a coming world revolution:

“All of a sudden people will wake up one day, after the Dow Jones has gone down by 7,000 points, and say: ”What the fuck is going on?” They’ll just see their life as they know it collapse around them. And then they’ll have to pick up the pieces and learn to live again.”

BBC News’ magazine had a great article on the history of disgust, and the role it plays in public discourse – did anyone else notice how often the word was used in connection with the News International hacking of Milly Dowler? The same issue covered the Darwin’s Emotions project at Cambridge, looking at a new effort to highlight and prove Charles Darwin’s contention that all humans can innately recognize the emotions behind facial expressions. The Centre’s Thomas Dixon wrote on this subject back in August.

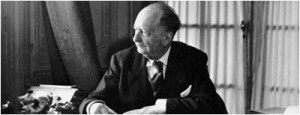

Finally, the Guardian had a good obituary of the philosopher, Peter Goldie. It noted Goldie’s unusual career path, from successful and feared financier of the Thatcher era to leading philosopher of the emotions:

The only link between Goldie’s two careers was his shrewd capacity for spotting a gap in the market – first with the neglected topic of emotions, later with the issue of conceptual art, which philosophy had previously ignored altogether, and then with issues of character, narrative and memory. But in philosophy this was a disinterested astuteness, the result of exasperation at why questions that had always preoccupied him had not been tackled, and at the way philosophers tend to set up polarised stances on any topic. His technique was to reject the polarities offered, yet fruitfully plunder each, ultimately pushing past both to a new resolution.

With emotions, for instance, he was least sympathetic to feeling theories, which tend to make an emotion virtually a self-enclosed bodily sensation, and only uneasily cater for its being essentially about people, actions and events. But Goldie also disliked the corollary deficiency in cognitivist theories, which, in making emotion a matter of judging that people and events are fearful, lovable, offensive or whatever, certainly account for emotion’s outward-directedness, but omit its visceralness.

You could, after all, be quite neutrally aware that someone is lovable without in fact loving them, or that someone’s behaviour is offensive without feeling offended; as (in Goldie’s illustrative analogy) a colour-blind person could have the capacity to accurately pick out colours which the normally sighted person actually experiences.

In order to avoid this awkward “add-on” of feeling to potentially impartial apprehension, Goldie’s neo-cognitivism proposed the notion of “feeling towards” – “thinking of with feeling” so that your emotional feelings are directed towards the object of your thought. Emotions, he said – with a nod both to David Hume and evolutionary theory – are useful in providing immediate practical responses (the flinch of disgust at rotten meat, for instance) that reason would be slower to achieve.

If you see any other articles we should mention, send them in. You can also follow us on Twitter @emotionshistory

It was a delicate issue. The activists who set up the camp are anarchists. They want to create ‘a society free from authoritarianism’, as a pamphlet put it at

It was a delicate issue. The activists who set up the camp are anarchists. They want to create ‘a society free from authoritarianism’, as a pamphlet put it at

Havi Carel had everything going for her. At 35, she had recently met the love of her life, she’d just brought out her first book, and she was about to start her dream job, teaching philosophy at the University of West England, in Bristol (UWE). The future looked bright. Then, she started to notice she lost her breath very easily. She had always been fit and healthy, yet suddenly she couldn’t keep up with her aerobics class, or walk up a hill while talking on her mobile. She thought she might be getting asthma.

Havi Carel had everything going for her. At 35, she had recently met the love of her life, she’d just brought out her first book, and she was about to start her dream job, teaching philosophy at the University of West England, in Bristol (UWE). The future looked bright. Then, she started to notice she lost her breath very easily. She had always been fit and healthy, yet suddenly she couldn’t keep up with her aerobics class, or walk up a hill while talking on her mobile. She thought she might be getting asthma.