For anyone who didn’t keep up with all our posts on the Queen Mary History of Emotions Blog this year, Thomas Dixon has made a selection of highlights from 2014 – a year of friendship and smiles, as well as tears and SAD-ness…

FRIENDSHIP

FRIENDSHIP

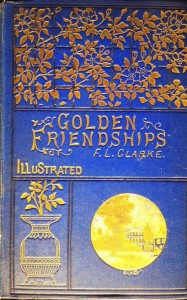

Much of my own energy in the first part of the year was devoted to writing and presenting a fifteen-part series for BBC Radio 4 – ‘Five Hundred Years of Friendship’ – tracing the changing meaning and experience of friendship across the centuries, from the world of ‘gossips’ and ‘goodfellows’ in the early modern period to the recent arrival of Facebook and online ‘friends’. The whole series is still available to listen to or download. Perhaps the most poignant and memorable episode, for me, in this centenary year of the outbreak for the First World War, was ‘A Battalion of Pals’ (Episode 10), in which I explored the wartime comradeship of ‘pals’ regiments alongside the meaning of friendship for E. M. Forster and other pacifist Bloomsbury writers. The emotional impact of World War One was again the subject of discussion when Professor Michael Roper gave our annual lecture, in November this year.

Alongside the BBC radio programmes on friendship, I commissioned a series of about 30 blog posts, designed to give interested listeners access to some of the best current scholarly work on the subject, which I had found out about in researching the series. I was fascinated to learn, for instance, about Naomi Pullin’s research on the extraordinary friendship of the Quaker women Katharine Evans and Sarah Cheevers who were imprisoned together in Malta, and about Michael Kay’s investigations into the early social history of the telephone, including its medical uses. Another notable contribution, on the subject of working-class friendship and ‘improvement’, came from Dr Helen Rogers and her undergraduate students working on the Writing Lives project at Liverpool John Moores University. In fact, I could write at length about what I learned from every single one of the blog posts, but I will resist that temptation and leave you to read the originals for yourself!

Alongside the BBC radio programmes on friendship, I commissioned a series of about 30 blog posts, designed to give interested listeners access to some of the best current scholarly work on the subject, which I had found out about in researching the series. I was fascinated to learn, for instance, about Naomi Pullin’s research on the extraordinary friendship of the Quaker women Katharine Evans and Sarah Cheevers who were imprisoned together in Malta, and about Michael Kay’s investigations into the early social history of the telephone, including its medical uses. Another notable contribution, on the subject of working-class friendship and ‘improvement’, came from Dr Helen Rogers and her undergraduate students working on the Writing Lives project at Liverpool John Moores University. In fact, I could write at length about what I learned from every single one of the blog posts, but I will resist that temptation and leave you to read the originals for yourself!

VISITING ARTISTS AND SCHOLARS

We have hosted several dynamic and energetic visitors to the Centre this year, including both artists and scholars.

Clare Whistler and Lloyd Newson were both Leverhulme Artists in Residence during the academic year 2013-2014. As part of his residency, Lloyd led two extremely well attended and successful events at QMUL, in collaboration with Dr Rhodri Hayward and others: one on the relationship between movement, music and text, and the other on verbatim theatre.

Clare Whistler’s residency, which was a collaboration linked to my own work on the history of weeping, investigated the emotional history of water – ‘Weather, Tears, and Waterways’. The residency is documented in a series of blog posts explaining the thinking and outcomes leading up to the ‘Vessels of Tears’ event in May 2014, including a post by PhD candidate Hetta Howes writing about the emotional meanings of water for women in the middle ages. We also worked with audio producer Natalie Steed to make three podcasts recording various aspects of the project, including an original composition by Kerry Andrew.

Dr Carolyn Pedwell was a AHRC visiting fellow at the QMUL Centre for the History of the Emotions during 2013-14 and organised a very successful (and over-subscribed) international symposium on ‘Transnational Affects’. Carolyn also gave a lunchtime seminar on her own work, a version of which was published on the blog: ‘Circuits of Feeling in the Age of Empathy‘.

GUEST POSTS

We publish discussions of the emotions and their history by colleagues beyond the core staff of the Queen Mary Centre – from other disciplines and other institutions. This year’s highlights included:

- Sally Holloway’s post for Valentine’s Day, remembering a love-lorn Georgian aristocrat.

- Jennifer Otter Bickerdike writing about the grave of Joy Division frontman Ian Curtis as site of memory and mourning.

- Fulvio D’Acquisto and Samuel Brod approaching the subject of emotions and health via immunology.

- Catherine Maxwell reviewing a wide-ranging new history of smell.

- Fanny Brotons exploring pre-modern religious and emotional attitudes to cancer.

- Joanne Kempner pondering the gender politics involved in the diagnosis and description of migraine.

NEW GENERATION THINKERS

We are proud that two members of our Steering Committee – Jules Evans and Tiffany Watt-Smith – have been chosen in the last two years to be BBC-AHRC New Generation Thinkers. Jules is the current co-editor of this blog, and Tiffany was the blog’s founding co-editor and is now a British Academy Postdoctoral Fellow in the School of English and Drama.

During 2014, as part of the New Generation Thinkers scheme, Jules made a short film about his work as a ‘roving philosopher’, using philosophy classes and ancient Stoic insights to promote wellbeing in the twenty-first century.

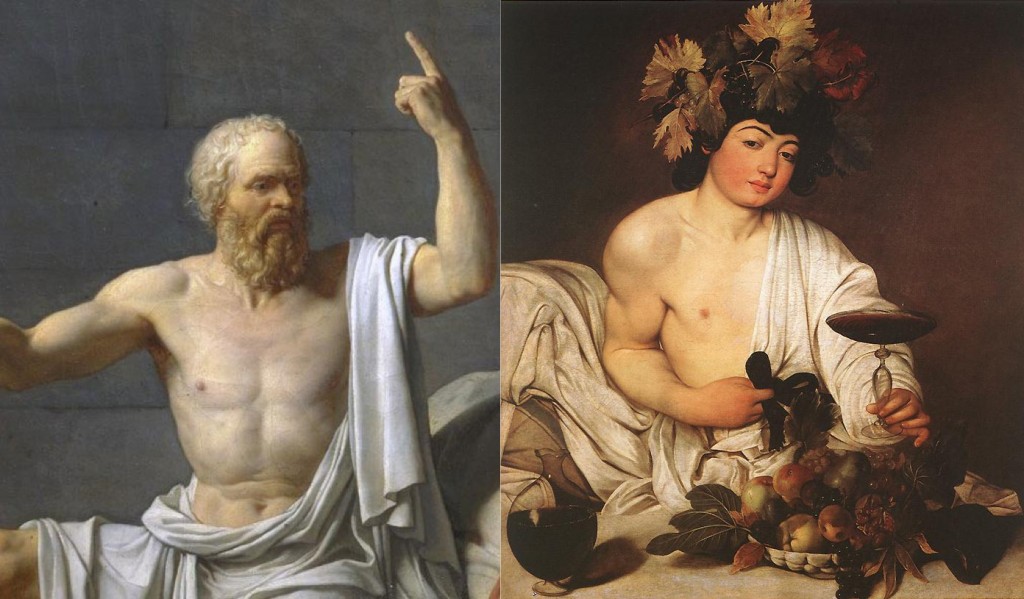

Aristotle, left, and Saracens’ Owen Farrell Photo: Alamy

Jules wrote a report for the blog about his AHRC-funded work on the benefits of practical philosophy, and an article for the Telegraph about his work at Saracens Rugby Club. He continues to contribute to this blog on a wide and fascinating range of subjects. His contributions this year included a commentary on a music video by Blondie as a commentary on Western ideas of rapture; an interview with Professor Jeff Kripal on the ‘mystical humanities’; and an essay on the shortcomings of neo-Stoic philosophies of emotion.

TIffany Watt-Smith wrote for the blog this year about giggling babies and the new science of laughter. In July, Tiffany presented an essay on BBC Radio 3 reassessing the symptoms and meaning of war neuroses and shell shock after World War One, in the light of her research. In November, she delivered a ‘Free Thinking Essay’ for the BBC Free Thinking Festival at Gateshead, which was also broadcast on BBC Radio 3: ‘The Human Copying Machine‘. Tiffany also contributed to two BBC radio programmes about the history and meaning of ‘boredom’ – The Why Factor, and Something Understood.

TIffany Watt-Smith wrote for the blog this year about giggling babies and the new science of laughter. In July, Tiffany presented an essay on BBC Radio 3 reassessing the symptoms and meaning of war neuroses and shell shock after World War One, in the light of her research. In November, she delivered a ‘Free Thinking Essay’ for the BBC Free Thinking Festival at Gateshead, which was also broadcast on BBC Radio 3: ‘The Human Copying Machine‘. Tiffany also contributed to two BBC radio programmes about the history and meaning of ‘boredom’ – The Why Factor, and Something Understood.

LOST EMOTIONS…. and BEYOND

The Centre’s PhDs and early career scholars continued their work spreading the word about the history of emotions. The ‘Lost Emotions Machine’ had several more outings, including an appearance at the Natural History Museum in June, which Eleanor Betts wrote about for the blog.

Chris Millard, one of the pioneers of the ‘Lost Emotions’ project, spent three months on secondment at the Parliamentary Office for Science and Technology, where he researched and wrote about the issues of ‘parity of esteem’. His work resulted in him co-authoring an editorial for the British Medical Journal, as well as writing a post for the history of emotions blog reflecting on the experience.

Jane Mackelworth, who is in the final stages of a PhD project on sapphic love in Britain in the twentieth century, recently wrote for us about the highly innovative community project she helped to run at the Bromley By Bow Centre – entitled ‘Love in Objects’ – which won Queen Mary’s Richard Garriott Prize for the best public engagement activitiy of the year.

Richard Firth-Godbehere reported on what he had learned about Begriffschichte and emotions at the 2014 Summer School run by our colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin, while Åsa Jansson offered her reflections on the transcultrual history of melancholy, arising from a conference she attended on the subject in Heidelberg.

SAD at 30

As the nights drew in, during November, we continued our more melancholy train of thought with a podcast produced by Natalie Steed to mark the 30th anniversary of ‘Seasonal Affective Disorder’. This podcast was a collaboration with our QMUL colleagues in the History of Modern Biomedicine Research group, headed by Professor Tilli Tansey, and arose from a joint witness seminar.

As the nights drew in, during November, we continued our more melancholy train of thought with a podcast produced by Natalie Steed to mark the 30th anniversary of ‘Seasonal Affective Disorder’. This podcast was a collaboration with our QMUL colleagues in the History of Modern Biomedicine Research group, headed by Professor Tilli Tansey, and arose from a joint witness seminar.

Earlier in the year Jules Evans had interviewed Norman E. Rosenthal, who wrote the first paper naming ‘SAD’ in 1984, for this blog. The transcript of the SAD Witness Seminar is now published and available to read in full.

FLINCHING, SMILING, TRANSFORMING THE PSCYHE

Among the highlights of 2014 for many of us were three brilliant new publications by members of our Centre.

Among the highlights of 2014 for many of us were three brilliant new publications by members of our Centre.

In January, Rhodri Hayward’s book, The Transformation of the Psyche in British Primary Care, 1880-1970 came out, followed in May by Tiffany Watt-Smith’s On Flinching: Theatricality and Scientific Looking from Darwin to Shell Shock.

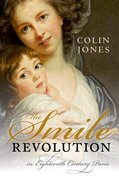

Colin Jones’s new book was publshed in September – The Smile Revolution in Eighteenth-Century Paris – and we carried a blog post by Colin to mark the occasion.

All three books would make ideal Christmas presents and, at the time of writing this, there may still be time to get your hands on a copy of one or all of them as last-minute gifts ….!

IN MEMORIAM

For all of us working on the history of emotions, around the world, the achievements of 2014 were tinged with sadness after the death, in June, of Professor Philippa Maddern, the founding director of the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions. Many friends and colleagues were moved to record their thoughts and recollections of Philippa in an online book of condolences.

One of the numerous ways in which Philippa’s contributions to the field will continue to be felt is through the work of a new journal – Ceræ: An Australasian Journal Of Medieval And Early Modern Studies – which was launched in 2014 with an inaugural volume on ‘Emotions in History’. The editorial committee of Cerae published their own collective tribute to Philippa, recalling the time and energy she devoted to supporting and mentoring them in their new initiative.

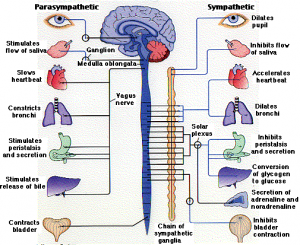

It seems to me that both accounts are true, both capture something important about the emotions. Perhaps, as Antonio Damasio argues, there are two different ways we can feel emotions – primary and secondary. Primary emotions are mainly autonomic and physiological. These occur in all animals, and perhaps to some extent in plants too. Secondary emotions, by contrast, involve some cognitive evaluations or re-evaluations, both of our physical response and of the stimulus that prompted it. Secondary emotions involve the neo-cortex, the most recently evolved part of our brain.

It seems to me that both accounts are true, both capture something important about the emotions. Perhaps, as Antonio Damasio argues, there are two different ways we can feel emotions – primary and secondary. Primary emotions are mainly autonomic and physiological. These occur in all animals, and perhaps to some extent in plants too. Secondary emotions, by contrast, involve some cognitive evaluations or re-evaluations, both of our physical response and of the stimulus that prompted it. Secondary emotions involve the neo-cortex, the most recently evolved part of our brain.