Dr Rob Boddice is a historian of science, medicine and the emotions, based at Freie Universitaet Berlin and McGill University, Montreal. His previous books include Pain: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2017) and The History of Emotions (Manchester University Press, 2018). His latest book is A History of Feelings (Reaktion, 2019), and he kindly agreed to discuss it in this special Q&A for The History of Emotions Blog. Asking the questions is the blog’s editor, Professor Thomas Dixon.

Dr Rob Boddice is a historian of science, medicine and the emotions, based at Freie Universitaet Berlin and McGill University, Montreal. His previous books include Pain: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press, 2017) and The History of Emotions (Manchester University Press, 2018). His latest book is A History of Feelings (Reaktion, 2019), and he kindly agreed to discuss it in this special Q&A for The History of Emotions Blog. Asking the questions is the blog’s editor, Professor Thomas Dixon.

Thomas Dixon: Thank-you so much for agreeing to this virtual chat! You have been a prolific and influential contributor to our field in recent years. Could I start by asking you – for the benefit of those who have not yet read them both – what is the difference between your two recent books – The History of Emotions and A History of Feelings?

Rob Boddice: The History of Emotions was commissioned to provide something that was missing at the time, namely a general introduction to the field, its principal works, theories and methods, while also looking at where we might go next. There were so many potential entry points, but no one-stop shop, as it were. Of course, in putting that together, and in taking the temperature of a field whose growth was pretty feverish, I realised that I had to do this in a critical manner. It is overtly not a neutral survey. I realised early on that I would have to walk the talk and show that one could do the history of emotions along the lines I was setting out. A History of Feelings, therefore, is an exemplification of the theories and methods set out in the first book. It’s an attempt to show that the critical methods are good for all periods and, indeed, to disrupt orthodoxies of periodization. Through a series of case studies or micro focuses, I offer one possibility for how a history of emotions – in a sort of epic mode – might look. It’s not the last word, by any means, and it has its limits, but it’s ambitious enough, wandering from ancient Greece down the present, and dealing along the way in Greek, Latin, Italian, French, German, and, most tricky of all, English.

Rob Boddice: The History of Emotions was commissioned to provide something that was missing at the time, namely a general introduction to the field, its principal works, theories and methods, while also looking at where we might go next. There were so many potential entry points, but no one-stop shop, as it were. Of course, in putting that together, and in taking the temperature of a field whose growth was pretty feverish, I realised that I had to do this in a critical manner. It is overtly not a neutral survey. I realised early on that I would have to walk the talk and show that one could do the history of emotions along the lines I was setting out. A History of Feelings, therefore, is an exemplification of the theories and methods set out in the first book. It’s an attempt to show that the critical methods are good for all periods and, indeed, to disrupt orthodoxies of periodization. Through a series of case studies or micro focuses, I offer one possibility for how a history of emotions – in a sort of epic mode – might look. It’s not the last word, by any means, and it has its limits, but it’s ambitious enough, wandering from ancient Greece down the present, and dealing along the way in Greek, Latin, Italian, French, German, and, most tricky of all, English.

TD: If it’s possible in a couple of sentences can you summarise the take-home messages that you would hope other historians of emotions would get from reading A History of Feelings? Would it be a new method, a new narrative, or something else?

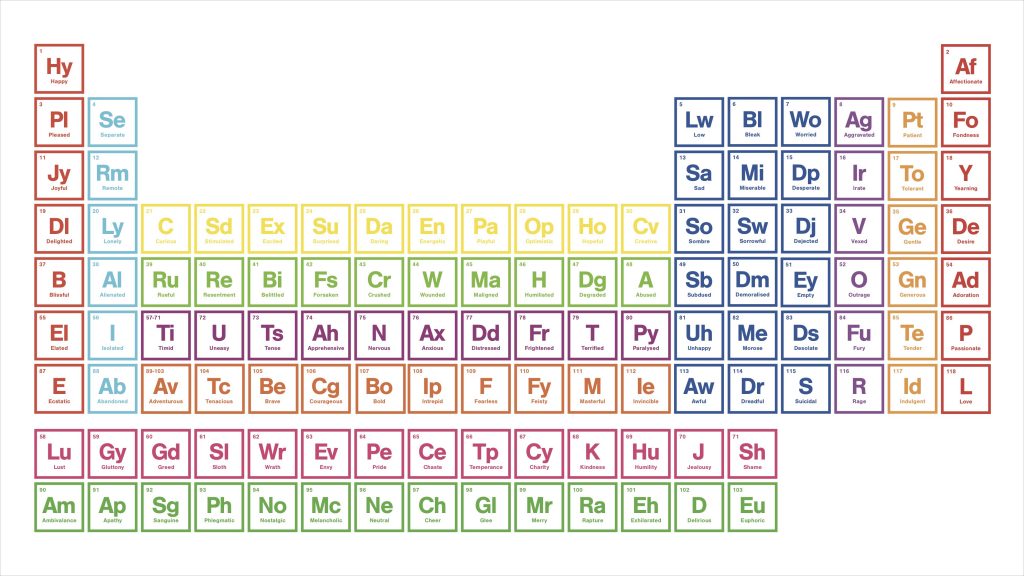

RB: Underlying this book as well as The History of Emotions is a deeply critical stance in opposition to a still powerful psychological orthodoxy that emotions in humans are universal, automatic, non-cognitive, natural, and so on. There are good reasons to think that the foundations of this orthodoxy have been thoroughly undermined, but it lingers nonetheless in the popular imagination, not least because it’s just so convenient. The premise that we understand something about human feeling in the past because, after all, we are human too, is almost overwhelming, but it’s fraught with problems. In A History of Feelings I reconstruct the felt past episodically in order to present past human experience as something unfamiliar or alien, understandable only through an appreciation of carefully reassembled context.

That word, ‘experience’, is also key. I’m trying to leave off the word ‘emotions’ – hence the title – to allow for the full play of situated experience, which does not necessarily fall into neat categories like ‘emotion’, ‘sense’ or ‘reason’. The book takes seriously the notion (borrowed from an increasingly culturally aware critical neuroscience) that the concepts available to a person are formative of experience, and that means treading carefully with contemporary conceptual categories. I want, above all, to avoid that easy projection of our own situated emotion knowledge onto past experience.

I suppose the last big message is connected to this. I am exhorting historians and general readers alike to become more critically reflexive about our own emotions: where do they come from? Who has a stake in shaping or directing them, and to what ends?

TD: You’re right that the universalist approach is still alive and well – as evidenced in this recent essay in Aeon magazine. In terms of your own approach to the history of emotions in this book, would it be fair to say that it is first and foremost by way of Western intellectual history?

RB: Partly, yes, but let me answer by way of another question that was put to me by Professor Brian Cowan when I launched the book in Montreal. He thought the book followed a sort of standard ‘western civ’ canon, not quite Plato to Nato, but near enough, and wondered why I’d structured the book in this way. My answer was to point out that I subvert the standard ‘western civ’ narrative at almost every turn. I employ a structure that follows the usual suspects – Homer, Thucydides, Plato, Aristotle, Augustine, von Bingen, Castiglione, Machiavelli, Descartes, Spinoza, Wollstonecraft, Smith, Paine, Darwin, etc – but I unpick the common understanding of ‘emotions’ in the works of these luminaries (understandings reached through modern translations that fall into the trap of thinking through a universal human nature) such that their affective content is almost unrecognisable. The narrative therefore implicitly undermines the logic of this ‘western civ’ structure and disrupts the standard periodization. I hoped to have written a sustained critique of ‘western civ’ by appropriating its outward form and messing royally with its content. There’s also a fair bit in here which goes beyond intellectual history to a history of affective practice, of sensing and emoting in discrete and contingent worlds. I try, throughout, not to lose sight of the doing of feelings. I do acknowledge, however, and I do so explicitly in the book, that the scope is geographically limited to the ‘west’, more or less. Given that so much of the emphasis here is in taking original languages seriously, that was a limit that I had to own. For now.

TD: Would you like to give an example of the way you try to subvert the standard periodisation?

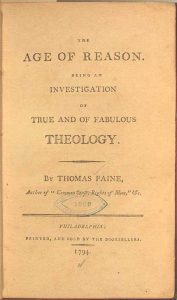

RB: There are several devices. Following Barbara Rosenwein’s complaint about the artificial characterisation of a pre-modern age of uncontrolled emotion — a childlike state — in contrast to a modern age of restraint, I upturn standard period references like ‘the age of reason’ and ‘the age of sensibility’. Both labels suggest an emergence out of this immature phase into something more refined and more civilized, and ‘the age of reason’ pits rational thinking against irrational emotion. I find that both characterizations privilege a certain view at the expense of a more textured intellectual and affective history. Hence, in A History of Feelings, I re-entangle thinking with movement, reason with sense and passion, to better represent lines of continuity with the past, but also to show that a significant rhetorical break toward reason was still steeped in affective construction.

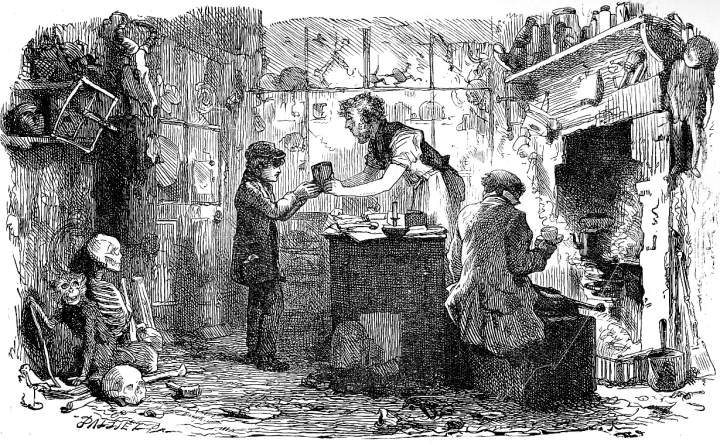

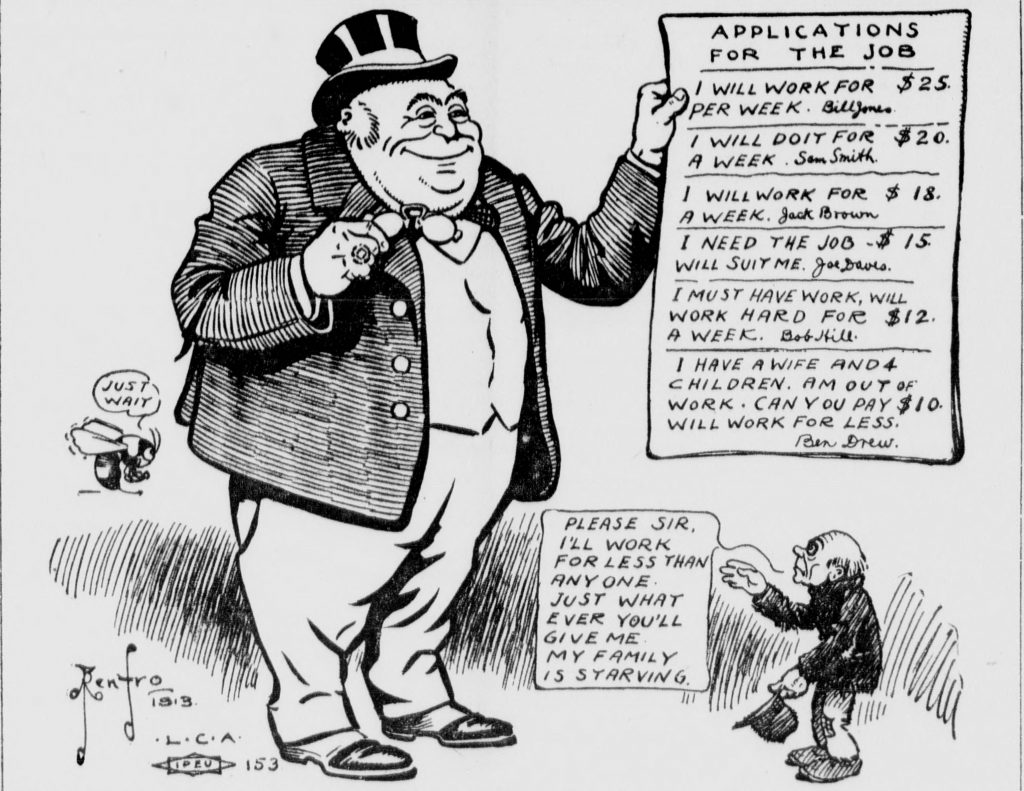

The Age of Reason, by Thomas Paine – one of the texts which is remembered as emblematic of the rationalism of the 18th century

By re-styling ‘the age of reason’ as the age of unreason, I gesture at the tendentiousness of recent celebrations of enlightenment rationality and highlight what gets overlooked by so doing. Reason, in this view, is an affect, or a sense, constructed for the times. Similarly, the ‘age of sensibility’ tends to focus on certain elite modes of feeling, at the expense of a tide of callousness. I don’t know anyone else who has stitched together the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as the age of ‘senselessness and insensibility’, but I think I make a good case for it. But aside from these kind of sweeping takes, I also focus tightly on the particulars of certain moments, showing that a forensic reconstruction of concepts and context can reveal acutely situated histories of feelings. They perhaps fit into a broader pattern, but they reward microhistorical attention.

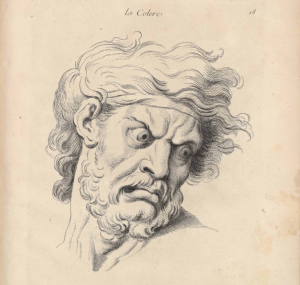

TD: One of the points on which I completely agree with you is that historians of emotions needs to pay careful attention to the language used by those they study, and to try to avoid anachronism. Could you maybe pick out one example of this from A History of Feelings that you think makes the point particularly well?

RB: The book begins with Homer’s Iliad. I’d be prepared to bet that anyone who has heard of this epic can tell you that it is principally about the ‘rage’ or ‘wrath’ of Achilles. ‘Wrath’, therefore, is famously and literally the first word in the western canon. Except that it isn’t. The first word is menis, and its translation to ‘wrath’ does something to the story that, to me, makes no sense at all.

Achilles’ wrath is associated with all the murderous and merciless killing he carries out in the last books of Iliad, as well as his extended desecration of Hector’s body. But the section of Iliad in which Achilles is active in this way comes after he has explicitly relinquished his menis. He is practicing something like ‘grief’ in these chapters (but ‘grief’ also underplays what is going on). In his menis, which lasts for the better part of the work, he is passive and withdrawn, and it is this that Homer asks the muses to ‘praise’ (the second word of Iliad) as a virtue. Achilles literally does nothing at all in his menis, which is praised as godlike, and which receives the sanction of Zeus. Whatever we call menis in English (I plumped for the rather clunky ‘Godlike menace’), we cannot call it ‘rage’ or ‘wrath’. To see Iliad as a long story of extreme anger that culminates in violence and death is a mistake wrought from a long-standing problem of reception (especially in Christian contexts): how can murderous, merciless Achilles be the hero? The history of this mistake is, in itself, interesting to pursue. But to begin again with the premise that Achilles is indeed the praised hero of Iliad has far-reaching consequences for our understanding of Homer’s cultural and political influence, especially in classical Athens.

TD: I totally agree about needing to rethink Achilles and menis, and I wonder what you think about the conundrum that I’ve found myself puzzling over in relation to my own work on “anger” – namely that if I am saying that orgē, and ira, and colère, and so on are not the same thing as the modern anglophone emotion of “anger” – then I need to explain why those other terms would feature in a history of “anger”. Our present day categories still seem to be setting the agenda, don’t they? I also wondered about this when you discuss, for instance, Aristotelian eudaimonia, or the American Declaration of Independence, alongside modern notions of “happiness” and subjective wellbeing. Aren’t you in danger of anachronism too?

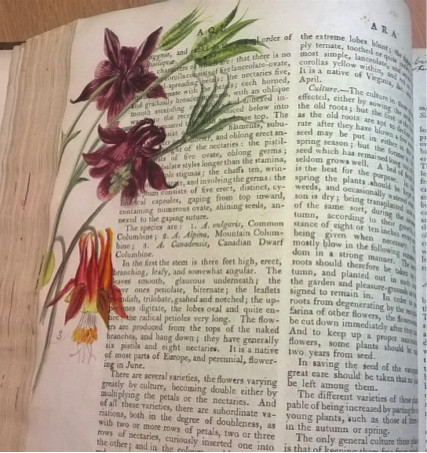

RB: The danger is ever-present, and there is no perfect solution. But we are in a process of undoing, of making unfamiliar that which has been assumed to be readily accessible. A colleague asked me something along the same lines, noting that I must have begun with the master English emotion categories in order to select the material I cover, and to some extent that is correct. The intent behind these selections, however, is to read the sources anew and, in some cases, to disrupt them beyond recognition. Most students never encounter sources in the original languages, and my intention has been to show exactly what gets sacrificed when we indulge the convenience of contemporary English translation — when we say Iliad is about ‘wrath’ or that Spinoza wrote an ethical treatise about ‘emotions’, for example. The effect, hopefully, is to de-essentialize the starting point — ‘anger’, in your example — and to make visible the assumptions that tend to be implicit in these master categories.

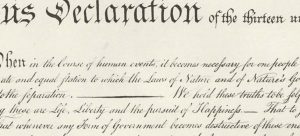

The Declaration of Independence (1776) refers to the rights to ‘Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness’

What follows is that we become circumspect about English as well, and treat it as an historical artefact in itself. I’m clear on this with respect to eudaimonia/happiness. The translation of ‘eudaimonia’ into ‘happiness’ in modern renditions of Aristotle is a convenience that ought not be countenanced. I follow the happiness agenda of positive psychologists to show how it is built on bogus assumptions, to ask what’s left of that agenda when it has been properly interrogated. Similarly with ‘happiness’ in the Declaration of Independence and Wollstonecraft’s exhortation to her lost love, ‘be happy’, I go to some lengths to say that if we mistake this word for what tends to be understood by ‘happiness’ today, then we make a grave error of interpretation. Concepts are situated, and that behoves us to understand their situation.

TD: Similarly, you try – again, for reasons I totally support – to avoid using the potentially misleading and anachronistic category of “the emotions”. But are other phrases you use such as “affective experience” or “affective life” any better from that point of view?

RB: On the face of it, no, but in practice yes. There will always be a gap between the reconstructed experience of the historical actor in its own terms and the analytical language of the historian that is at a distance from it. The risk with ‘emotions’ is that the general reader assumes, a priori, to know what they are. Quite a few historians of emotion are guilty of this too. By using the adjectival form ‘affective’ in this way I’m consciously shaking up what most psychologists understand by the word ‘affect’ (valence, arousal, etc., something non-cognitive, automatic, natural), trying to employ it in such a way as to send the reader’s attention back to the historical situation at hand in order to define what I mean by ‘affective experience’. I realise, as I am working on a major theoretical shift to the history of experience, that ‘experience’ itself has its own tricky intellectual history, but compared with ‘emotions’ I prefer its breadth and flexibility, its capacity to include emotion, sense, reason, and practice, among other things. Further justification is forthcoming, in next year’s Emotion, Sense, Experience (Cambridge University Press), written with Mark M. Smith of sensory-history fame.

TD: This is really interesting and I am sure that others will want to follow-up on these ideas and respond to your work on this point. I look forward to seeing your CUP book with Mark M. Smith when it comes out. A History of Feelings is packed with thought-provoking re-readings of texts and images from the past and I thought I’d end by inviting you to say a few words about one that I found especially intriguing – a seventeenth-century French document called the ‘Map of Tender’. What is the significance of that example to you?

RB: I was put onto the Carte de Tendre by Professor Michele Cohen, whose kitchen-table conversation has often proved inspirational for me. I’m not sure I read it in the same way she did, but I was gripped by this document — actually a kind of board game for the Parisian salonières — which shows various routes to the land of Tendre, either through the social practices of service or of courtship, or else via the dangerous direct route of inclination.

The map is loosely structured on the anatomy of the uterus, and the route of tendre d’inclination — i.e. following one’s feelings — risks overshooting into the Dangerous Sea — a turmoil of hysteria. It’s fascinating for so many reasons, not the least of which has been the loose translation of tendre into ‘love’, which misses more than it reveals. I render it more straightforwardly as ‘tender(ness)’, but that entails a long explanation. The map not only showed how to cultivate this feeling (and its risks), but also showed how to do it, such that feeling and convention, affective relations and social practices, are absolutely entangled. I then employ the map for a discussion of the ‘tender emotion’ over time, which was for a long period a master category that included love, but much else besides, and which is now seemingly lost and alien to us. This is all the more surprising given its centrality to the work on emotions of such luminaries as Alexander Bain, Herbert Spencer and Charles Darwin. It was a part of the fabric of elite social life, relationship building, and essential to the understanding of civilised society. Yet by the twentieth century it had virtually disappeared. I think it’s a great example of why work in this field is important.

TD: Thanks so much for sharing your thoughts about your fascinating book!