I wasn’t a big reader as a youth. I was more of a jock and a class clown. It was only around the age of 17 that I suddenly became a moody adolescent book-worm – it was both a quickening and a sickening. In one term, I read Hamlet, King Lear, Heart of Darkness and Freud’s Five Cases of Hysteria, and also watched Blue Velvet. Strong medicine! I had a sudden horrifying and fascinating sense of the dark subconscious bubbling beneath civilized appearances.

I wasn’t a big reader as a youth. I was more of a jock and a class clown. It was only around the age of 17 that I suddenly became a moody adolescent book-worm – it was both a quickening and a sickening. In one term, I read Hamlet, King Lear, Heart of Darkness and Freud’s Five Cases of Hysteria, and also watched Blue Velvet. Strong medicine! I had a sudden horrifying and fascinating sense of the dark subconscious bubbling beneath civilized appearances.

The book that made the biggest impression on me, by far, was Friedrich Nietzsche’s Birth of Tragedy. I was transfixed by his description of the play of two opposing forces in ancient Greek culture – the Apollonian, which seeks limits and moderation, and the Dionysian, which seeks excess and ecstasy. I started to see these forces everywhere. Every essay I wrote weaved its way inevitably back to the Apollonian and the Dionysian. The obsession continued at university. Fifteen years later, I wrote my first book on the Socratic path to flourishing, and my second on the Dionysian path. How long a shadow that book has cast!

Strangely enough, I never read other books by Nietzsche. I got my Nietzschean philosophy second-hand, from the novels of DH Lawrence. But recently I was sent a new biography of Nietzsche by Sue Prideaux, called I Am Dynamite. I devoured it – it’s a beautiful, moving, and very absorbing account of a heroic and pathetic life. And it inspired me to read more Nietzsche, and consider influence on our time a little more deeply.

Nietzsche grew up in a fairly well-to-do German family in Prussia, but the family fortunes took a turn for the worse when his father – a Lutheran pastor – died of a degenerative brain illness in his 30s. The family became hard-up, but Nietzsche lifted them up through his academic brilliance. He was appointed a professor of philology at the age of 25, but he dreamt of being a composer. He managed to befriend Richard Wagner – already a European celebrity – and spent the happiest days of his life at the Wagner castle, where he was embraced as one of the family. For a few years, he moved in the exalted atmosphere of Chateaux Wagner – all high ideals and swooning ecstasies.

But his 30s were not as glorious as his 20s. He wrote The Birth of Tragedy at 28, but it was greeted with ominous silence by the press and academic peers. It was so over-the-top in its ecstatic style, compared to the average plodding academic work. Then he fell out with Wagner, and fell in love with a 20-year-old Russian, named Lou Salome, who ultimately rejected his advances and humiliated him. He was prone to terrible migraines and digestive troubles, and was often confined to bed for days. He found himself tramping across Europe, from city to city, self-publishing his own books, and almost always alone.

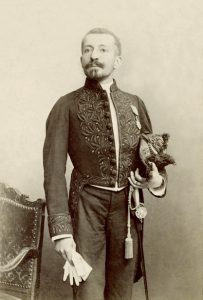

Nietzsche in a humorous photo with his friend Paul Ree and 20-year-old Russian tearaway Lou Salome. The three lived in a sort of Platonic menage a trois for a while, before Lou and Paul abandoned the besotted Nietzsche. He became markedly more misogynistic afterwards. ‘You go to women?’ he wrote. ‘Do not forget the whip.’

Yet somehow, out of these inauspicious circumstances, his ideas burst forth, more and more confident and radical. He was certain that he had an entirely new vision of existence, which would destroy the last 2500 years of morality, and pave the way for a bold new adventure for mankind.

When one reads the great prophets of moral philosophy – the Buddha, Plato, the Stoics, Christ, the author of the Upanishads – one notices that they all preach self-knowledge, self-examination, self-control, sobriety, chastity and asceticism of the body. Only through this self-denial, we are told, can the virtuous person go beyond desires and appetites, beyond appearances, beyond impermanence, and arrive at some transcendental resting place – the One, God, the Logos, Buddha-nature, Brahman.

Nietzsche, through his great ‘transvaluation of values’, turns all these systems on their head. Their morality is not virtue and health. It is sickness, weakness, pessimism, nihilism, a symptom of decadence and decline. It is the consolation of the weak, the broken and the disappointed, those who turn wearily from life and ‘put their last trust in a sure nothing rather than an uncertain something’.

He writes, perhaps with the Buddha in mind: ‘They encounter an invalid or an old man or a corpse, and straightaway they say ‘Life is refuted!’ But only they are refuted, they and their eye that sees only one aspect of existence.

These famous moral systems are really an outgrowth of ‘slave morality’. The slave-philosopher Epictetus is a perfect example. He has no power over external things, so he says that true power, true freedom, is power over one’s thoughts and desires. How convenient. Then, like Socrates, he preaches this acceptance-of-weakness to strong aristocratic youth, and ruins them.

The ‘slave-morality’ was first invented by the Jews, Nietzsche says, out of their weakness and domination by various more powerful races. Judeo-Christianity pretends to be a morality of meekness and forgiveness, but underneath that mask lurks resentment and passive-aggression. ‘I forgive you’, they say to their conquerors, but what they really mean is ‘I’m better than you’. And the Romans, alas, fell for it.

Against the slave-morality, Nietzsche champions the masters, the ‘blond beasts’, those strong, carefree warriors who maraud across the world from time to time, like the Vikings, the Teutonic knights, the Mongols, the Indian Kshatriyas, the Greek aristocrats. They were young, healthy, vigorous, laughing, cruel and violent. They basically did what they liked, and called it ‘noble’, and had a gay old time of it until Socrates, Jesus, Lao Tse and the Buddha came along and ruined everything.

Nietzsche thought that liberal democracy was really an extension of Christianity, with its sympathy for the weak and the rights of man. He looked across late 19th century Europe, with its campaigns for universal suffrage, gender equality and the welfare state, and saw the triumph of slave morality, the triumph of the herd, the masses, the little people. It made him sick. He railed against the plebs, and especially against female suffrage – ‘the struggle for equal rights is a symptom of sickness’, he wrote. Healthy women loved to obey men. Only barren women fought for equality.

Democratic, plebeian, mediocre Europeans had lost any sense of greatness. They’d lost even the memory of God and of their predecessors’ heroic struggle for transcendence. They just wanted comfort and ‘well-being’. Nietzsche was no fan of well-being:

You want, if possible—and there is not a more foolish “if possible”—TO DO AWAY WITH SUFFERING; and we?—it really seems that WE would rather have it increased and made worse than it has ever been! Well-being, as you understand it—is certainly not a goal; it seems to us an END; a condition which at once renders man ludicrous and contemptible—and makes his destruction DESIRABLE! The discipline of suffering, of GREAT suffering—know ye not that it is only THIS discipline that has produced all the elevations of humanity hitherto?

Instead, he lays out a new vision for humans, a new project: the Ubermensch, or Superman. He writes in Thus Spake Zarathustra: ‘I teach you the Superman. Man is something that should be overcome.’ We should seek to transcend ourselves not in the service of ‘super-terrestrial hopes’ like God or Nirvana, but rather in the service of self-actualization. This self-actualization – becoming what we are – does not involve the disciplining of the body, the emotions and the desires, but rather letting the desires, emotions and body sing and dance. It does not mean a weary obedience to rules and precepts handed down by priests, but rather the bold creation of new values. Man creates meaning, he does not receive it from God. And this self-actualization will be here and now, in this body, on this Earth, or it will be nowhere. We must resist the urge to find consolation and security in fake metaphysical dreams like God or Nirvana, and instead learn to dance with uncertainty and chaos.

Instead, he lays out a new vision for humans, a new project: the Ubermensch, or Superman. He writes in Thus Spake Zarathustra: ‘I teach you the Superman. Man is something that should be overcome.’ We should seek to transcend ourselves not in the service of ‘super-terrestrial hopes’ like God or Nirvana, but rather in the service of self-actualization. This self-actualization – becoming what we are – does not involve the disciplining of the body, the emotions and the desires, but rather letting the desires, emotions and body sing and dance. It does not mean a weary obedience to rules and precepts handed down by priests, but rather the bold creation of new values. Man creates meaning, he does not receive it from God. And this self-actualization will be here and now, in this body, on this Earth, or it will be nowhere. We must resist the urge to find consolation and security in fake metaphysical dreams like God or Nirvana, and instead learn to dance with uncertainty and chaos.

By 1888, Nietzsche felt he had blown his way clear of the old morality, and was euphoric with the new prospects he saw for mankind. He wrote four books in nine months, they poured out of him. He was filled with joy, and even lost control of his face and his emotions – he couldn’t stop grinning. He saw coincidences in everything. ‘He only had to think of a person for a letter from them to arrive politely through the door.’ His letters to his friends became increasingly manic. He started to allude to himself as Dionysus, or ‘The Crucified’. ‘I shall rule the world from now on.’ ‘In two months time I shall be the foremost name on the earth’.

In January 1889 he had some sort of breakdown in the streets of Turin. It is said he saw a man whipping a horse, and he clung to the horse’s neck and wept. How poignant if this is true – the man who condemned pity breaks down in pity! He retreated to his apartment, where he screamed and danced naked. His friend Franz Overbeck was contacted, and found Nietzsche cowering in a corner, trying to read his writings but obviously unable to comprehend them. He never recovered his mind – never seemed to know who he was or what was happening.

He was 44, but lived for another 11 years. His sister Elizabeth, who sounds an evil and selfish anti-Semite, took care of him, and cashed in on his growing success. She ran salons celebrating his work in the living-room, while Nietzsche howled in his bedroom upstairs. She controlled his estate, and turned him into a prophet of Nazism. Hitler came to visit, and emerged from their conversation bearing Nietzsche’s walking stick.

Was Nietzsche’s collapse a divine punishment for his hubris and over-reaching? Some kind of psychosis or spiritual emergency? Or a neurological illness, perhaps inherited from his father? We don’t know. But, just as he prophesized, in the years after his collapse his influence grew and grew. His dynamite philosophy blew a hole in Victorian complacency, and created a space for the fierce experimentation of modernism.

For some years after World War 2, Nietzsche was understandably out of fashion. But he’s been rehabilitated since the 1970s, and is now one of the most popular subjects for philosophy PhDs. Scholars have clarified that, unlike his sister, he wasn’t anti-Semitic – he admired Jewish culture. Nor was he a nationalist – he thought nationalism was a cheap intoxicant, despised German militarism, and called himself a ‘good European’. He was a key influence on Michel Foucault and Jacques Derrida, and helped to create what Paul Ricoeur called the ‘hermeneutics of suspicion’ which is so popular in left-wing humanities and social sciences: what secret interest lurks under an ideal? Aren’t all claims to ‘truth’ or ‘beauty’ really disguised power-grabs by particular interest groups?

This new biography will add to his good reputation – what a heroic man we meet, what a stylist, what a humourist! Who else has chapter headings like ‘Why I am so clever’! Who else can tear apart an entire philosophy (like Stoicism) with a few hilarious sentences. What brilliant psychological insights he threw up in his inspired frenzy – on the unconscious, the ego, projection, the wisdom of the body.

It’s awkward, then, that this new, sympathetic, rehabilitated Nietzsche should prove to be so popular with the alt-right. The American neo-Nazi Richard Spencer has said he was ‘Red Pilled by Nietzsche’, and many other angry young white men on alt-right or Red Pill websites have nothing but praise for Nietzsche. They don’t get him, insist liberal or leftist defenders of Nietzsche. They’re misappropriating him. They’re making the same mistakes the Nazis made.

Oh come off it. Foucault is right that there are many Nietzsches, but one of the most consistent notes one hears is contempt for the masses and hatred of liberal democracy, equality, and the rights of women, workers or the weak. As I read his books this week – particularly Beyond Good and Evil and The Genealogy of Morals – I thought how well it fit with the alt-right worldview: Liberal democracy is a monstrous cacophony that seeks to shame and emasculate strong men. It is a dictatorship of the offended, the resentful, and the easily bruised, who seek power through victimhood and hurt feelings. This conspiracy of the weak will only work if strong men fall for it – if they become cuks or ‘white knights’, in alt-right and Red Pill terms – if they are so credulous as to believe that women or minority groups really are interested in ‘equality’ and ‘fairness’ rather than simply power and domination. But the strong man, the Alpha male, will break the bonds of liberal guilt and roam free, just like Trump, Bo-Jo, Bolsonaro, Orban, Duterte, Erdogan, Berlusconi, and every other blond or not so-blond beast now strutting on the world stage.

How could the alt-right and Red Pillers not thrill to passages like this, where Nietzsche gets nostalgic about the good ol’ days of rape and pillage enjoyed by the ‘blond beasts’:

They enjoy freedom from all social control, they feel that in the wilderness they can give vent with impunity to that tension which is produced by enclosure and imprisonment in the peace of society, they revert to the innocence of the beast-of-prey conscience, like jubilant monsters, who perhaps come from a ghostly bout of murder, arson, rape, and torture, with bravado and a moral equanimity, as though merely some wild student’s prank had been played, perfectly convinced that the poets have now an ample theme to sing and celebrate.

It reminds one of Kavanaugh – it’s all just student pranks…just bants!

There are passages where Nietzsche even sounds like Trump – in his insults against women, and his absurd boasting: ‘At no moment of my life can I be shown to have adopted any kind of arrogant or pathetic posture’, he says, before continuing: ‘Anyone who saw me during the seventy days of this autumn when I was uninterruptedly creating nothing but things of the first rank which no man will be able to do again or has done before, bearing a responsibility for all the coming millennia, will have noticed no trace of tension in me.’ It reminds me of Trump’s immortal line: ‘I’m much more humble than you would understand’.

How could fascists not grin at Nietzsche’s Strangelovian denunciations of the superfluous dwarves of liberal democracy, who don’t deserve any sympathy – in fact, it is just this sympathy which has led to the ‘DETERIORATION OF THE EUROPEAN RACE’? How could they not cheer at his calls for ‘the higher breeding of humanity, together with the remorseless destruction of all degenerate and parasitic elements’, at his yearning for ‘the harshest but most necessary wars’, at his praise of violence and cruelty as the source of all higher culture, at his endless comments like: ‘The weak and the failures shall perish. They ought even to be helped to perish’.

I could give many such quotes. Nietzsche can’t be called a fascist or alt-righter, because he never stayed in one position long, and he rejected any political action as ‘filth’. But the alt-right can find a lot to love in him. I’m sure sometimes he is being provocative – just bants! – but words and ideas easily slip off the page and kill people.

And this champion of strength and virility was a sickly and weak man, a failure in the army, a loser in love, who claimed not to need public attention yet became more and more megalomaniac until he claimed to be a god. He’s right that there can be something morbid and unhealthy in Stoicism and other philosophies of consolation – but there is also, surely, something morbid and resentful in him, the impoverished and humiliated Prussian constantly insisting on his aristocratic rank. One can find him interesting, funny, fascinating, even sympathetic, and still be honest about the toxicity of his ideas and the damage they do.

William M. Reddy is William T. Laprade Professor Emeritus of History and Professor Emeritus of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University. His many scholarly contributions to the history of emotions include The Navigation of Feeling (2001) and The Making of Romantic Love (2012). He is co-editor of the book series Palgrave Studies in the History of Emotions.

William M. Reddy is William T. Laprade Professor Emeritus of History and Professor Emeritus of Cultural Anthropology at Duke University. His many scholarly contributions to the history of emotions include The Navigation of Feeling (2001) and The Making of Romantic Love (2012). He is co-editor of the book series Palgrave Studies in the History of Emotions.

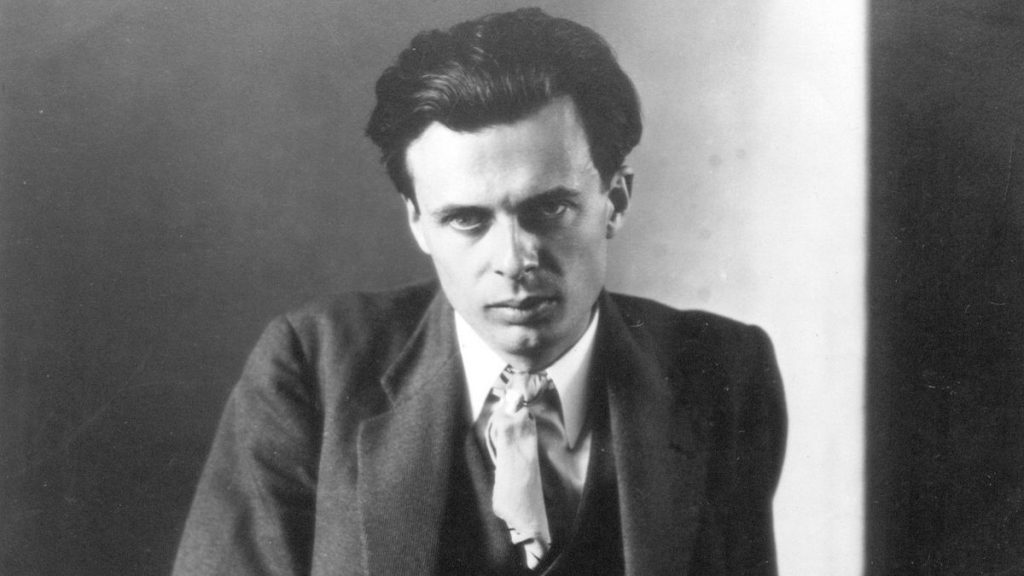

I’m researching a book about Aldous Huxley and his friends Alan Watts, Christopher Isherwood and Gerald Heard, and how these four posh Brits moved to California and helped to invent the modern culture of ‘spiritual but not religious’.

I’m researching a book about Aldous Huxley and his friends Alan Watts, Christopher Isherwood and Gerald Heard, and how these four posh Brits moved to California and helped to invent the modern culture of ‘spiritual but not religious’.

Riana’s current research focuses on social cognition and, in particular, empathy. Her research is informed by her background in cognitive science and time spent working in labs, conversing with practising scientists. She completed her PhD in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at Cambridge. Prior to returning to Cambridge as a Teaching Associate, she spent two years as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research (KLI) in Klosterneuburg, Austria (near Vienna).

Riana’s current research focuses on social cognition and, in particular, empathy. Her research is informed by her background in cognitive science and time spent working in labs, conversing with practising scientists. She completed her PhD in the Department of History and Philosophy of Science at Cambridge. Prior to returning to Cambridge as a Teaching Associate, she spent two years as a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research (KLI) in Klosterneuburg, Austria (near Vienna).