:origin()/pre04/e2e6/th/pre/i/2011/263/7/f/dissolve_by_noctulius-d4aesm8.png) At the end of last year, an unusual article appeared in the Journal of Psychopharmacology. A single dose of a drug appeared to dramatically reduce anxiety and depression in those suffering from life-threatening cancer, far better than any other treatment. The drug was psilocybin, the psychedelic found in magic mushrooms.

At the end of last year, an unusual article appeared in the Journal of Psychopharmacology. A single dose of a drug appeared to dramatically reduce anxiety and depression in those suffering from life-threatening cancer, far better than any other treatment. The drug was psilocybin, the psychedelic found in magic mushrooms.

The two trials, by NYU medical school and Johns Hopkins medical school, are the latest in a series of recent studies which claim psychedelics have remarkable therapeutic powers, helping people overcome chronic emotional disorders and addictions. So how exactly does a single dose of a psychedelic drug create such radical personality changes?

The Johns Hopkins study wrote: ‘This finding suggests a potential psycho-spiritual mechanism of action: the mystical state of consciousness.’

Come again?

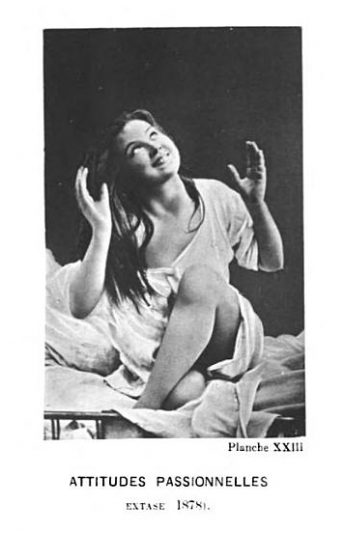

A late 19th century photo from the Salpetriere hospital showing a hysteric patient in ecstatic attitude

For over three centuries, western science – and in particular, psychiatry – has tended to pathologize ‘mystical experience’, to reduce it to a delusion or mental illness. In the Enlightenment, natural philosophers called it ‘enthusiasm’, and blamed on an over-active imagination or an over-warm brain. In the late 19th century, psychiatrists labelled it ‘hysteria’. In the 20th century, spiritual experiences were (and still are) reduced to brain disorders like schizophrenia or epilepsy.

The consequence of this long pathologization of ecstasy is that there’s a taboo around such experiences. As Aldous Huxley put it: ‘If you have an experience like this, you keep your mouth shut, for fear of being told to go to a psychoanalyst’, or, in our day, a psychiatrist. And the result of that taboo is that western culture has become spiritually flat, afraid to let go, stuck in our heads and our egos, lacking a window to transcendence.

In the last few years, however, a consensus has begun to emerge in psychology and psychiatry that ecstatic experiences – moments when we go beyond our ordinary ego and feel a connection to something bigger than us – are often good for us.

Scientists can’t agree on what to call this sort of experience – it’s variously studied as self-transcendence; flow; mystical, religious, spiritual or anomalous experience; altered states of consciousness; or (my preferred term) ecstasy. But scientists do agree that it’s an important human experience that can be very healing. This is a big shift for western science, and western culture.

Breaking the mental loop

Ecstasy is good for us because it gets us out of our head. Emotional disorders like depression, anxiety and addiction are perpetuated by rigid and repetitive patterns of thinking, feeling and acting. We get stuck in loops of negative rumination, endlessly thinking about ourselves and our imperfections. We can free ourselves from these rigid mental habits by using rationality to unpick our beliefs – this is what Cognitive Behavioural Therapy does.

But we can also get out of these loops by shifting our consciousness. To use the terminology of the New Testament, we can have sudden epiphanies which break us out of the tomb of our egos, giving us the experience of being born again. Being reborn – suddenly reconfiguring the self – is a fundamental human capacity, not found only in followers of Jesus.

There are shallower and deeper forms of ego-loss. At the lighter end of the spectrum, there are the sort of ‘flow’ states which we might find each day or week, where we lose ourselves in reading a good book, or walking in the park, or going for a run. These activities settle and absorb our consciousness, taking us out of the loop of rumination, helping us forget ourselves in the moment (here’s an interview I did with flow psychologist Mihaly Czikszentmihalyi on flow and ecstasy).

Iris Murdoch called it ‘unselfing’. She wrote:

We are anxiety-ridden animals. Our minds are continually active, fabricating an anxious, usually self-preoccupied, often falsifying veil which partially conceals our world…The most obvious thing in our surroundings which is an occasion for ‘unselfing’ is what is popularly called beauty…I am looking out of my window in an anxious and resentful state of mind…Then suddenly I observe a hovering kestrel. In a moment everything is altered. The brooding self with its hurt vanity has disappeared. There is nothing now but kestrel.

Nature is the most reliable route to this sort of ego-dissolving wonder. When we go for a walk, run, ride or swim in nature, we might discover what Wordsworth called ‘the quiet stream of self-forgetfulness’. We get into the ‘reverie’ that Rousseau wrote about when he went walking, feel a mind-expansion at the beauty of the landscape, and this breaks the loop of rumination. Here’s a 2015 study on how a 90-minute walk in nature reduces rumination.

The arts can do something similar – absorb our consciousness so that we lose ourselves in the moment, in the book, poem, play, painting, song, cathedral etc – and this shift in consciousness breaks the loop of rumination and takes us somewhere quieter, better, more spacious. A 2016 mass survey by Durham University found reading and nature were our favourite ways to rest – and switching off the restless ego-mind is an important part of that. Likewise, meditation and prayer can help us find the space between our ruminating thoughts. Many of us use sport as a way to get out of the noise of our head and into our bodies.

Such moments of absorption can be very socially connecting. Suddenly, we’re taken out of our ego-loops and joined in what social psychologist Jonathan Haidt called ‘the hive mind’. That’s a great antidote to the chronic western affliction of loneliness. We might get that experience singing, dancing, marching or playing music together, which studies shows helps to synchronize people’s breathing and even heart-beat. We might get collective flow from playing or watching sport together, or participating in a concert or political rally. Or – the oldest route – we might get it by worshipping the divine in some form or other.

The deep end of absorption

And then there are deeper moments of self-transcendence, which the mystics call ‘ecstasy’, in which one becomes so absorbed in a moment or activity that one’s identity and conception of reality are radically altered, perhaps permanently. Such moments are rare, but they can be life-changing. At this deeper end of what I call the ‘continuum of absorption’, one finds experiences like strong psychedelic trips, moments of deep contemplation, spontaneous spiritual experiences, and near-death experiences.

Take spontaneous spiritual experiences. In surveys, between 50% and 80% of people say they have experienced a moment of ecstasy, where they’ve gone beyond their normal sense of identity and felt a deep connection to something greater than them. Here’s one example:

During my late 20s and early 30s I had a good deal of depression. I felt shut up in a cocoon of complete isolation and could not get in touch with anyone…things came to such a pass and I was so tired of fighting that I said one day, ‘I can do no more. Let nature, or whatever is behind the universe, look after me now.’ Within a few days I passed from a hell to a heaven. It was as if the cocoon had burst and my eyes were opened and I saw. Everything was alive and God was present in all things….Psychologically and for my own peace of mind, the effect has been of the greatest importance.

In a survey I did, agnostics and atheists also reported moments where they felt a deep connection between themselves and all things – indeed, arch-rationalist Bertrand Russell had a mystical moment where he suddenly felt profoundly connected to everyone in the street. He said that experience turned him into a pacifist. We might make sense of such moments of connection differently, but they seem very common, and on the whole good for us.

Psychedelics are similarly effective at giving people a sense of spiritual connection and oneness. Comedian Simon Amstell has spoken of how a psychedelic brew called ayahuasca, found in the Amazon jungle, helped him overcome depression: ‘Before I left I felt broken. After I came back, I didn’t feel broken anymore…I felt like I was part of the world, not disconnected from it.’

After 40 years in the wilderness, psychedelics are rapidly returning to the mainstream of western medicine. Just this month, the Lancet published a trial showing the effectiveness of ketamine at treating chronic depression, while BBC One’s main daytime TV show, Victoria, had a segment on the benefits of LSD microdosing in managing emotional problems. Other trials have found psychedelics effective at treating depression and addiction.

One of the most powerful forms of ecstatic experience is the ‘near-death experience’. Thanks to improved resuscitation procedures, NDEs are increasingly common and there are several academic research units studying them. They seem to share common features, particularly an encounter with a white light and a sense of being profoundly loved. People typically return from NDEs less afraid of death, because they no longer think it’s the end. I had an NDE myself when I was 21 – that’s how I became interested in this topic – and it helped me recover from PTSD. After five years of feeling my ego was permanently broken, I realized there was something within me bigger than my ego, which was loved and OK.

Other forms of ecstatic experience seem to work in a similar way – they take people beyond their constructed ego and give them a sense of love-connection to some greater whole. In the trials I mentioned at the start of this article, psilocybin seemed to give the participants an NDE-type experience. Here’s the report of one participant in the NYU study:

For the first time in my life, I felt like there was a creator of the universe, a force greater than myself, and that I should be kind and loving. I experienced a profound psychic shift that made me realize all my anxieties, defences and insecurities weren’t something to worry about.

Now, this poses a challenge for western science. It appears that moments of ecstasy or ‘mystical experiences’ can be very therapeutic. But are they true? Are we really connected to all beings and the universe in some kind of psychic love-connection? Is there really a loving God beyond our ego? Tucked away in the formal language of the Johns Hopkins study is the comment that one psychedelic trip increased people’s belief in the afterlife (see the passage below), and this was one of the factors in the reduction of death-anxiety:

Remarkable: a material that makes us believe in the immaterial. But is that just a placebo-delusion?

We don’t know. Maybe such experiences give people an insight into a genuine connection between our consciousness and all things, a connection that materialist physics doesn’t yet understand but might in the future. Or maybe the experience of oneness is really in our head – recent studies appear to show that both LSD and meditation improve brain connectivity, so parts of the brain that don’t normally talk to each other come online and connect. Maybe that’s what the blissful feeling of oneness ‘is’. We don’t know. But we do know such experiences are often healing.

However, there are risks to ecstasy as well. Ego-dissolution is a form of radical surgery, as it were, which shakes people out of their usual habits of thinking and feeling and allows them to press re-set. That can be dangerous if it’s not done with proper therapeutic support. It can release buried trauma, or latent psychosis. It can be difficult to go back to one’s previous life.

I’ve had personal experience of the negative effects of psychedelics, for example, after I had a bad LSD trip when I was 18 which left me struggling with paranoia and post-traumatic stress for several years. Scientists have also studied frightening experiences of ego-loss that emerge from meditation. Spontaneous spiritual experiences can be terrifying and hard to integrate or explain to other people, particularly in a highly secular and ecstasy-averse culture like Europe.

Even some communities which put a positive value on ecstasy can be harmful. New Age or charismatic Christian communities are one of the few places in western culture where we still have permission to trance out and dissolve our egos. But such communities can put a rigidly dogmatic interpretation on ecstatic experiences – either they’re Jesus, or the Devil. They may foster an ecstatic sense of togetherness, but at the cost of demonising outsiders. They may lead to the toxic worship of a guru-figure who triggers the ecstasy. They may cash in on people’s craving for exaltation.

Having studied ecstasy over the last five years, I’ve come to two conclusions. Firstly, we need a more balanced relationship with ecstasy. We shouldn’t be averse to it or embarrassed to talk about it. Ego-transcendence is not bonkers, it’s natural and good for us. But we shouldn’t get hung up on it either, and start thinking we’re incredibly special for having a spiritual experience (we’re not). They’re just part of the long journey towards awakening.

I feel like western culture is a bit like a balloon – because there’s such a flattening of the ecstatic in the mainstream of our culture, it bulges out in other areas (the New Age, charismatic Christianity), in which there’s too strong an emphasis on it.

I feel like western culture is a bit like a balloon – because there’s such a flattening of the ecstatic in the mainstream of our culture, it bulges out in other areas (the New Age, charismatic Christianity), in which there’s too strong an emphasis on it.

Secondly, we need to develop controlled spaces to lose control. That’s what religious rituals have provided humans for millennia, and what the West lost in the Reformation and Enlightenment. Since then, we’ve improvised many new places for transcendence – from cinema to New Age cults to acid house to football hooliganism. But not all of these new places are healthy.

One new place for ecstasy is therapy and medicine. Ecstasy is returning to the mainstream of western culture thanks to medical research in fields like psychedelic science and contemplative science, which shows ecstasy is healing. The benefits are potentially huge, but the risk is that scientists become priests, and the Gospel of Mindfulness or Psychedelics becomes the new dogma.

A second new ‘space’ for ecstasy is the internet, where people come together to share their ecstatic experiences online. We’re in an era of mass experimentation in ecstasy – rather than look to priests or gurus, we self-experiment, then sharing our results with others through online and offline communities like www.erowid.com, where users share their trip experiences; or meditation sites like reddit.com/r/Meditation; or in self-help groups like the Hearing Voices network.

Such communities are an example of a new, wired spiritual democracy: no one is in charge, everyone is an expert. I imagine virtual reality will take this online mass ecstasy one stage further – though here the replacement for the church will be the corporation (Facebook etc) which manages and monetizes the online communion. And there’s a risk that, in our desperation to share our ecstasy online, it ends up being just another selfie.

Alongside these new spaces for ecstasy, I think we in the West need to find a way to re-engage with existing religious traditions, particularly our inherited tradition of Christianity, which we mock in public while endlessly stealing from the backdoor. Christianity, for all its flaws, teaches us how to embed ecstasy in an ethical context of humility, charity and surrender to Something More than the self.

Some modern forms of ecstasy – the New Age, the occult, the human potential movement, transhumanism – often encourage humans to get pumped up on ecstasy to try and become super-powered gods. This seems like dangerous ego-inflation to me. We have something godlike within us, but the way to connect to it is not by flying off into ungrounded superhero fantasies, but by sitting down quietly and accepting our weakness and imperfection. ‘We descend by self-exaltation’, said St Benedict, 1500 years ago, ‘and ascend through humility.’

This article summarises some points from my new book, The Art of Losing Control, which explores how people find ecstasy in modern western culture. You can buy the book here (it’s also available in Kindle and paperback).

This article summarises some points from my new book, The Art of Losing Control, which explores how people find ecstasy in modern western culture. You can buy the book here (it’s also available in Kindle and paperback).

It’s been a tough week for the UK – mental illness went up 164%. Previously, mental health charities assured us that

It’s been a tough week for the UK – mental illness went up 164%. Previously, mental health charities assured us that

:origin()/pre04/e2e6/th/pre/i/2011/263/7/f/dissolve_by_noctulius-d4aesm8.png) At the end of last year,

At the end of last year,

I feel like western culture is a bit like a balloon – because there’s such a flattening of the ecstatic in the mainstream of our culture, it bulges out in other areas (the New Age, charismatic Christianity), in which there’s too strong an emphasis on it.

I feel like western culture is a bit like a balloon – because there’s such a flattening of the ecstatic in the mainstream of our culture, it bulges out in other areas (the New Age, charismatic Christianity), in which there’s too strong an emphasis on it.