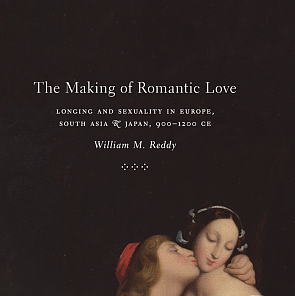

Professor William M. Reddy was one of the keynote speakers at the recent SSHM conference on “Emotions, Health and Wellbeing” at Queen Mary. He has very kindly agreed to post on the History of Emotions blog the following paragraphs, which were not included in the paper delivered on 11 September due to lack of time. Posted below the text is the full list of references for the lecture. Professor Reddy’s most recent work is a study of the medieval roots of romantic love, which will be reviewed in a future post on this blog.

Professor William M. Reddy was one of the keynote speakers at the recent SSHM conference on “Emotions, Health and Wellbeing” at Queen Mary. He has very kindly agreed to post on the History of Emotions blog the following paragraphs, which were not included in the paper delivered on 11 September due to lack of time. Posted below the text is the full list of references for the lecture. Professor Reddy’s most recent work is a study of the medieval roots of romantic love, which will be reviewed in a future post on this blog.

Evidence appears to be accumulating in favor of theories that see a close connection between cognition and affect, as I indicated in my paper presented on 11 September. (See provided list of references.) As several observers have noted, we appear to be on the verge of setting aside a distinction between reason and emotion that has a long history in Western understandings, going back to the fourth century BCE. The reason / emotion distinction may itself represent not the cutting of nature at its joints, but a conception that plays a central role in certain local emotional vocabularies used in Western venues. Of course, if this is the case, the term emotion has to be used with scare quotes around it, and the history of emotions must address a wider range of issues than simply what has been thought about emotions and how they have been experienced—as if “emotion” itself were an unproblematic concept. The notion of reason has itself, in effect, been used in a variety of Western emotional styles over the centuries, in the service of a variety of norms.

But this is not the first time in Western history that the distinction between emotion and reason has been subjected to critical reevaluation and even rejection. The failure to find a modular system within the brain underlying specific emotions—as outlined in Lindquist et al. (2012), Pessoa and Adolphs (2010), and other studies—might be compared to the famous experiments of Charles Bonnet and Abraham Trembley in the 1740s. They cut arms, mouth, stomach away from freshwater polyps, and found that the polyps readily regenerated the missing parts. They cut polyps into pieces, and found that each separate fragment of the polyp was capable of regenerating the whole organism. (Here I am following discussions in Baertschi and Gaukroger.[1]) The possibility that nature could generate organisms in this way suggested that matter itself might possess an intrinsic principle of activity or life. Buffon, whose Histoire naturelle appeared in 1749, speculated that mechanists, from Galileo to Newton, had taken the external qualities of objects—extention, impenetrability, motion, external shape, divisibility, communication of motion in collision and through the action of springs—as fundamental principles of matter. But, Buffon asks, “ ‘Is it not the case that, if our senses were different from what they are, we would recognize qualities in matter different from these?’” (X, 328). Buffon does not want to exclude these mechanical principles, but suggests we could add to them.[2]

Having puzzled over the development of the foetus, Maupertuis also argued in 1751 that matter itself must contain some kind of life principle. “If all of [the parts of the embryo] have the same tendency [that is, a uniform attraction similar to gravity], the same force for coming together with each other, why do some go to form the eye, others the ear?; why do they form this wonderful arrangement? … If we want to come to terms with this, even if only by analogy, we need to have recourse to some principle of intelligence, to something similar to what we call desire, aversion, memory.’”[3]

These same years, 1739-52, saw the major publications of Albrecht von Haller, the Göttingen professor of medicine who argued that muscle activity arose from an irritability that “belonged to the glutinous component of muscle fibers … in the same way that gravity belongs to matter.” For Haller, this principle of irritability in muscular tissue combined with the principle of sensibility of tissue imbued with nerves to create the capabilities of movement of the animal organism. Robert Whytt of Edinburgh in 1751 rejected as “absurd” the idea that “matter can, of itself, by any modification of its parts, be rendered capable of sensation, or of generating motion.”[4] Haller responded with counterarguments, sparking a wide-ranging debate.

Denis Diderot took the views of Buffon, Maupertuis, Haller, and others and pushed them to a radical conclusion, that (1) the line between animals and plants was arbitrary, with many intermediate forms such as polyps that had characteristics of both, and the line between plant and mineral might also be a gray one; (2) that sensibility was a characteristic of all matter comparable to, and in addition to, matter’s responsiveness to gravity; and (3) that human sensory experience and human thought itself were no more than a realization of this sensibility. In making sensibility the origin of all human thought in this way, Diderot was downplaying the thought-emotion distinction and granting certain emotions an unprecedented primacy within experience. Diderot hesitated between the view that sensibility could make itself manifest prior to the existence of organization and the view that a specific organization of matter (the animal body) brought out the latent sensibility of matter, rendering it active. Either way, Diderot insisted, sensibility was responsible for all human mental activity.[5]

By promoting this view Diderot was attempting to link the aesthetic and moral theories of Dubos, Shaftesbury, Hutcheson, and others; the speculations of naturalists such as Maupertuis and Buffon; the new medical understanding, especially vis-à-vis the nervous system, represented in the works of Cheyne, Haller, and others; as well as the vivid melodramatic narratives of novelists such as Samuel Richardson. Diderot brought them all together in a single vision of human nature. While Diderot’s views were not accepted by all, concern with knitting together the implications of developments in all these areas was widespread, and there were strong scientific and philosophical reasons for concluding, as Hume famously put it, that reason “is and ought only to be the slave of the passions, and can never pretend to any other office than to serve and obey them.”[6] This conclusion was rendered more palatable by the general rejection of the doctrine of original sin, which had seen the weakness of the will in relation to passion as a mark of divine punishment. There were certain passions that remained dangerous, in the view of many, but other “feelings” or “sentiments”—the expressions of sensibility—came to be widely regarded as the foundation of human virtue.

For Diderot and many others, then, states of absorption tinged with feelings of pity, love, gratitude, or cheerful affection were “natural” in the physiological sense and also “natural” in the moral sense. Naturally social, human beings found pleasure in sentiments that bound them together.

The eighteenth-century experience can serve as a cautionary tale for the present. As with Bonnet and Trembley’s dissections of freshwater polyps, so in current brain imaging. No matter how finely one slices the brain, each piece seems to contain both cognitive and affective components, just as each piece of a polyp was able to regenerate the whole organism. The hypotheses offered by Buffon, Maupertuis, Diderot, that each part of the organism possessed a principle that Diderot and others called “sensibility,” could be compared to the background assumption of much cognitive and neuroscience research, i.e., that the brain is engaged in “information processing,” by analogy with a computer. Previously, “affective” processing was viewed as a separate system that interfered with or overrided cognitive “information processing.”[7] Now, affective processing has been elevated to equal status with cognitive processing; both, therefore, appear to involve “information.” Watson and Crick’s discovery of the structure of DNA, as based on an amino-acid code, capable of containing and replicating vast amounts of information, offered the possibility of a striking (and purely “mechanistic”) answer to Maupertuis’s insistence that there must be some “principle of intelligence” underlying the unfolding of embryonic development. Likewise, the anatomy of the neuron has offered grounds for seeing the nervous system as a processor of information.

In the last twenty years, however, neuroscientists have dropped the idea that this processing is “linear” in character. (In linear processing, each stage of processing is completed before the results are passed on to the next stage. As I have noted elsewhere, a good example of a model of linear processing is Saussurian structural linguistics.) The elevation of affect to equal status with cognition is no more than a single dimension of this more general transformation. Processing in the brain is now seen as “massively parallel,” and generally characterized by “top-down” or “cascade” patterns (in which later stages of processing begin before earlier ones are completed, and feed early, sketchy results back down the chain to speed the completion of earlier-stage tasks). Although the precise wiring is far from agreed upon, it is generally agreed, for example, that, in vision, object-recognition at early processing stages is facilitated by a preliminary guess, based on low-resolution information. This guess (or set of related guesses) is rushed back down to early-stage visual cortex regions to check for possible matches. Evidence of similar top-down processing has been found for speech recognition, where semantic processing begins well before phonetic and syntactical processing are completed, as well as, spectactularly, for pain, where efferent (outgoing) pathways have been found reaching all the way out to the pain receptors distributed throughout the body. In general, efferent pathways are as numerous and as rich as afferent (in-going) ones in the nervous system, suggesting that all early-stage processing is “assisted” or shaped by late-stage top-down assistance—some of which is cross-modal (e.g., information from hearing may be used to interpret visual perception of a moving mouth, as in the so-called McGurk effect). The involvement of late-stage “cognitive” regions of the prefrontal cortex in “regulating” the responses of the amygdala, central to the “emotion regulation” paradigm, is just another case of top-down processing (Ochsner & Gross, 2007).

One must wonder, as the understanding of this extraordinary architecture deepens, whether it will be necessary to drop the “information processing” analogy entirely, just as the notion of sensibility was dropped in the nineteenth century. The brain seems designed to leap to conclusions about the environment on the basis of the barest hints of information. There would be plentiful grounds for thinking of this as a kind of “construction” of one’s environment, except that the patterns themselves derive from learning and habituation that are made possible by the existence of an environment that is, indeed, quite stable in many respects. In addition, these rapid-fire pattern recognition propensities are subject to reshaping by practice. Everything depends on how highly “activated” a given guess about a pattern has become. And activation, in turn, depends in large measure on repetition. Hence, again, the centrality of what might be called “striving.” “Striving to feel” might be useful as a catch phrase, to replace the notion of “self-fashioning,” characteristic of the linguistic turn.

(c) 2012 William M. Reddy.

[1] Bernard Baertschi, Les rapports de l’âme et du corps: Descartes, Diderot, et Maine de Biran (Paris: Vrin, 1992), 34-41, 101-133; Stephen Gaukroger, The Collapse of Mechanism and the Rise of Sensibility: Science and the Shaping of Modernity, 1680-1760 (Oxford: Clarendon, 2010), 357-420.

[2] Gaukroger, Collapse of Mechanism, 365.

[3] Quoted in Baertschi, Les rapports, 37; and in Gaukroger, Collapse of Mechanism, 362.

[4] Quoted in ibid., 397.

[5] Two texts are central to understanding Diderot’s views: the article animal in the Encyclopédie and the Entretiens avec d’Alembert of 1761.

[6] Quoted from the Treatise in Daniel Gross, The Secret History of Emotions: From Aristotle’s Rhetoric to Modern Brain Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006), 98.

[7] See, for a good example of this kind of approach to affect, Keith Oatley, Best Laid Schemes: The Psychology of Emotions (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992).

William M. Reddy

“Striving to Feel: The Centrality of Effort in the History of Emotions,” paper delivered to the conference of the Society for the Social History of Medicine, on the theme “Emotion, Health, and Well-Being,” at QMUL, Center for the History of Emotions, 11 September 2012

List of references

Davis, Elizabeth L., Linda J. Levine, and Heather C. Lench, “Metacognitive Emotion Regulation: Children’s Awareness That Changing Thoughts and Goals Can Alleviate Negative Emotions,” Emotion 10(2010):498-510

Eagleman, David M., Incognito: The Secret Lives of the Brain (New York: Pantheon, 2011).

Gross, James J., “The Future’s So Bright, I Gotta Wear Shades,” Emotion Review 2(2010):212-216

Gross, James J., and Lisa Feldman Barrett, “Emotion Generation and Emotion Regulation: One or Two Depends on Your Point of View,” Emotion Review 3(2011):8-16

Havas, David A., et al., “Cosmetic Use of Botulinum Toxin-A Affects Processing of Emotional Language,” Psychological Science 21(2010):895-900

Hollan, Douglas, “Emotion Work and the Value of Emotional Equanimity Among the Toraja,” Ethnology 31(1992):45-56

Jones, Matthew L., The Good Life in the Scientific Revolution: Descartes, Pascal, Leibniz, and the Cultivation of Virtue (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006)

Kellermann, Tanja S., et al., “Modulating the Processing of Emotional Stimuli by Cognitive Demand,” Social, Cognitive, and Affective Neuroscience, 7(2012):263-273

Kron, Assaf, et al., “Feelings Don’t Come Easy: Studies on the Effortful Nature of Feelings,” Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 139(2010):520-534

Lindquist, Kristen A., et al., “The Brain Basis of Emotion: A Meta-Analytic Review,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 35(2012):121-143—with 28 comments and a reply from the authors in this issue, on pp. 144-202

Niedenthal, Paula M., et al., “Embodiment of Emotion Concepts,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 96(2009):1120-1136

Ochsner, Kevin N. and James J. Gross, “The Neural Architecture of Emotion Regulation,” in Handbook of Emotion Regulation, edited by James J. Gross (New York: Guilford, 2007), 87-109

Pessoa, Luiz, “On the Relationship Between Emotion and Cognition,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 9(2008):148-158

Pessoa, Luiz, and Ralph Adolphs, “Emotion Processing and the Amygdala: From a ‘Low Road’ to ‘Many Roads’ of Evaluating Biological Significance,” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 11(2010):773-782

Rosaldo, Michelle Z., Knowledge and Passion: Ilongot Notions of Self and Social Life (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1980)

Dr Stephanie Downes is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Melbourne, where she is part of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions. Here she reviews Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving the Atocha Station for the History of Emotions Blog.

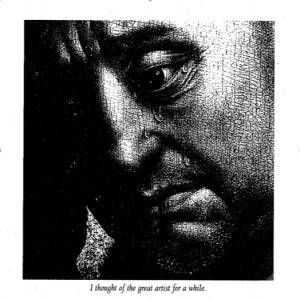

Dr Stephanie Downes is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Melbourne, where she is part of the ARC Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions. Here she reviews Ben Lerner’s novel Leaving the Atocha Station for the History of Emotions Blog. The passage is accompanied by a black and white close-up of the face of the man on the right of Weyden’s painting. Suddenly, we’re reading faces, reading art, as well as text. The image, incidentally, is remarkably reminiscent of the close-up of Bouts’ Mater Dolorosa (c. 1460), which appears on the cover of James Elkins’ Pictures and Tears: A History of People who have Cried in Front of Paintings (Routledge, 2001). All this has made me think more about responses to, rather than representations, of emotion in literature. If we cry in front of a painting, or while reading a book, do those tears still convey ‘real’ emotion? Does emotion have to be lived to be experienced? Hamlet-like: ‘What is Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba,/ That he should weep for her?’ (2.2.448)

The passage is accompanied by a black and white close-up of the face of the man on the right of Weyden’s painting. Suddenly, we’re reading faces, reading art, as well as text. The image, incidentally, is remarkably reminiscent of the close-up of Bouts’ Mater Dolorosa (c. 1460), which appears on the cover of James Elkins’ Pictures and Tears: A History of People who have Cried in Front of Paintings (Routledge, 2001). All this has made me think more about responses to, rather than representations, of emotion in literature. If we cry in front of a painting, or while reading a book, do those tears still convey ‘real’ emotion? Does emotion have to be lived to be experienced? Hamlet-like: ‘What is Hecuba to him, or he to Hecuba,/ That he should weep for her?’ (2.2.448) While Lerner’s narrator looks at the weeping stranger, and we look at Van der Weyden’s weeping man, he wonders: ‘Maybe this man is an artist, I thought; what if he doesn’t feel the transports he performs’ (10).

While Lerner’s narrator looks at the weeping stranger, and we look at Van der Weyden’s weeping man, he wonders: ‘Maybe this man is an artist, I thought; what if he doesn’t feel the transports he performs’ (10).

Liz Gray

Liz Gray

Take this Bower bird nest. Can it be seen as a piece of sculpture in its own right? It is thought to serve a purpose in attracting a mate, but it is perhaps a more elaborate means than some other birds adopt. Robins are satisfied with their red breasts, blackbirds have their song, so why do bower birds feel the need to build such elaborate structures? And can they not be regarded as sculptures, and as such an art form? I do not admit to being able to provide an answer to these questions – at least not yet anyway.

Take this Bower bird nest. Can it be seen as a piece of sculpture in its own right? It is thought to serve a purpose in attracting a mate, but it is perhaps a more elaborate means than some other birds adopt. Robins are satisfied with their red breasts, blackbirds have their song, so why do bower birds feel the need to build such elaborate structures? And can they not be regarded as sculptures, and as such an art form? I do not admit to being able to provide an answer to these questions – at least not yet anyway.