Richard Firth-Godbehere is a Wellcome Trust funded PhD Candidate in the Medical Humanities at QMUL, trying to work out how revulsion came to be associated with the word ‘disgust’ in the middle of the seventeenth century, and how revulsion and repulsion were understood before this point. In this blog post he reports on the 2014 Summer School on emotions and Begriffsgeschichte at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development in Berlin.

At the end of September 2014, I attended a Summer School dedicated to the topic of ‘Concepts, Language and Beyond: Emotions between Values and Bodies’ at the Max Planck Institute for Human Development, Berlin. Over five and a half days, a panel made up of academics and PhD candidates from around the globe, and faculty members from the institute’s own Centre for the History of Emotions gathered to struggle with the question of how Begriffsgeschichte, (Conceptual History), could shake off its linguistic shackles and move beyond into the worlds of the visual, material, the emotions and embodiment.

The school heard presentations, debated set texts, and discussed short texts and presentations by attendees on various topics around a number of main themes: Temporality, power, religions and secularity, translation, and affect theory. There were three main reoccurring areas that resurfaced throughout the week: Spatiality, Temporality and Power. This will be an overview of these main reoccurring points and what I learned from my time there, after the most obvious question has been addressed: what is Conceptual History?

What is Begriffsgeschichte?

Begriffsgeschichte, or Conceptual History, is a particular type of history that attempts to reach basic concepts through the language used to describe them. It will, for example, take a concept like ‘civility’ and examine the ways those words related to ‘civility’ – its semantic net – develop over time, changing the meaning of the concept as they do so. This way of approaching a history of ideas was first formulated by Reinhart Koselleck, particularly in his six volume collective work Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe (Basic Historical Concepts). In his 1972 introduction to the work, Koselleck explained that his methodology entailed identifying ‘basic concepts’, or as he explained ‘not those technical terms registered in the handbooks methodological works of historical scholarship … but those defining concepts (Leitbegriffe) which must be studied historically’. This includes key terms, self-characterisations, slogans and ‘concepts which claim to the status of theory (including those of ideology)’.[1] The idea is that as the semantic nets relating to these concepts change their meanings, so do the meanings of the concepts themselves and the one can be interpreted through the other. This could be a powerful method, especially when applied to the language surrounding emotional concepts, but it does have its drawbacks. Those drawbacks, and attempts to surmount them, were the primary focus of the summer school.

Concepts in Space

The first reoccurring problem is that of transnational and multi-lingual Conceptual History. For example, how can a methodology that focuses on semantic nets be applied to Transnational or even Global History? The worries here are many. Do the concepts related to those words share any family resemblance at all from culture to culture? It is true that concepts do cross borders, but how can Conceptual History follow that transfer without entering into the further problems of translation? Is it possible to find a universal, global, basic concept without imposing Eurocentric or North American assumptions that might distort what that concept really means in, say, India? It seems to me that this is not simply a problem of transnational historiography, but one that can exist within nations. For example, how do we know a well-educated elites understanding of the concept of love is the same as that of an illiterate worker? How can we be sure that a Latin text discussing the passions yields a semantic net that can be mapped onto a vernacular text? A thorny knot indeed, and perhaps one that Conceptual History alone will find difficult to untangle.

This focus on the spatial aspect of Conceptual History also arose when discussing visual culutres. This extra-linguistic spatial element seems to be missing from Conceptual History altogether. When we visited Gemäldegalerie, Berlin’s excellent pre-Renaissance art collection, my repeated asking of the tried and trusted questions – ‘where did this come from?’ ‘where was it in the building?’ ‘who commissioned it?’ ‘how much did it cost?’ etc. – seemed almost like I was uttering a foreign language (and in fact I was speaking English, so technically, I was). Yet, for Conceptual History to break free from linguistic shackles, it cannot be afraid to use methodologies that have served other disciplines, such as visual cultures, so well.

Concepts in Time

Another important part of the discussion focused on temporality. Central to this was Koselleck’s idea of layers of time, as well as the methodological problems and opportunities of Ernst Bloch’s idea of nonsynchronicity and the barely translatable Die Gleichzeitigkeit des Ungleichzeitigen: the synchronicity of the nonsynchronous or the simultaneity of the non-simultaneous. This is best expressed through Koselleck’s phrase, ‘it is, after all, part of our own experience to have contemporaries who live in the Stone Age’ (Reinhart Koselleck, The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts, trans. Todd Samuel Presner, Stanford University Press, 2002, p. 8). Putting the teleological and Eurocentric implications of Koselleck’s words to one side, concepts develop, wax and wane, at different speeds in different places. In emotions, it is perhaps William Reddy’s Emotional Regimes and Barbara Rosenwein’s Emotional Communities that can best exemplify this. An understanding of hate that is understood or expected by one section of society may not be by another, who holds onto older, newer, or rediscovered conceptions of hate that are quite at odds.

Another important part of the discussion focused on temporality. Central to this was Koselleck’s idea of layers of time, as well as the methodological problems and opportunities of Ernst Bloch’s idea of nonsynchronicity and the barely translatable Die Gleichzeitigkeit des Ungleichzeitigen: the synchronicity of the nonsynchronous or the simultaneity of the non-simultaneous. This is best expressed through Koselleck’s phrase, ‘it is, after all, part of our own experience to have contemporaries who live in the Stone Age’ (Reinhart Koselleck, The Practice of Conceptual History: Timing History, Spacing Concepts, trans. Todd Samuel Presner, Stanford University Press, 2002, p. 8). Putting the teleological and Eurocentric implications of Koselleck’s words to one side, concepts develop, wax and wane, at different speeds in different places. In emotions, it is perhaps William Reddy’s Emotional Regimes and Barbara Rosenwein’s Emotional Communities that can best exemplify this. An understanding of hate that is understood or expected by one section of society may not be by another, who holds onto older, newer, or rediscovered conceptions of hate that are quite at odds.

This leads to another temporal worry, that of anachronism. One of our discussions, inspired by Margrit Pernau’s research, focused on the concept of nostalgia as a political emotion in late-nineteenth and early-twentieth-century India. The immediate problem here was: can you really describe people from another culture in another time as having felt ‘nostalgia’ in a western, modern sense? The answer seems to be in how you frame the concept. If the study explicitly states that it is using the term ‘nostalgia’ (or ‘disgust’ or ‘love’) in an instrumental, or even anthropological, way, then that would be fine. Saying ‘I am using nostalgia as we know it in only to see what was going on and being expressed in this particular instance’ would allow similarities and differences, even the very existence or non-existence of the emotion, to be teased out. If, however, you were to reach back into the past and impose a modern concept onto it, that would be deeply problematic.

Concepts of Power

Power was a topic expressed implicitly and explicitly. Concepts of power, particularly the use of the word ‘Injury’ in the run up to the Opium Wars and ‘Terrorism’ as an instantly vilifying and othering word, were discussed, but often the power in question was found in other areas. For example, what power or powers were responsible for concepts changing? How do we identify that? How political are these concepts? Should we examine such concepts through philosophical and elite expressions of them or from below? If the later, how can an area like subaltern studies – the study of those whose voice is all but lost from history, or those who are oppressed by another group – get to these concepts without, as was suggested, redefining what a subaltern group is? These questions seem, to me, to be the thorniest issues surrounding attempts to take Conceptual History beyond text and lead to another set of questions. For example, how do you approach the political and power relationships of the body through Conceptual History? Could this be done through the study of how the bodies and sense were used in the formation of cultures? How could you apply the ideas of Conceptual History to politically motivated building projects, such a communal living, or religious architecture and its associated artwork?

An answer was suggested using a fascinatingly Lockean idea that Concepts are understood as the sum of how our senses understand the external, objective, material world. This means it could include words as well as related images, emotions, sounds, expressions and other things related to this. The example given by Imke Rajamani in her talk on ‘Anger in popular Hindi cinema: Exploring a concept beyond language’ was the Bollywood genre of ‘Angry Young Man’ films and its multisensory depiction of anger through colour, facial expression, elements of mythology – in this case the beliefs surrounding Diwali – and expected tropes in the soundtrack. This was interesting, and as with visual cultures, is a kind of analysis that practitioners of Visual Anthropology, Visual Sociology, and film studies do rather well. To take methods from these disciplines would be a good way forward, but it does not take us any closer to the examination of power.

In addition to the power at play in history, the conversation also regularly returned to power and politics flowing through the historian his or herself, especially the thorny issue of Eurocentrism. When exploring concepts beyond borders, in others’ bodies, and across social groups, the historian wields a great deal of power. Conceptual Historians can easily write in concepts that did not exist, putting words into people’s mouths and badly translating historical ideas into modern European concepts. Ultimately, it is the historian who has the power to change concepts and meaning from one constructed era to another, not the people of the time, and this power relationship has to be carefully balanced before the genuine political and power relationships can be understood. The same is true with emotions: it is easy to take modern emotional concepts and try to find them in the past, as in the case of nostalgia. This leads me to the biggest problem I see in the whole endeavour.

Conclusion

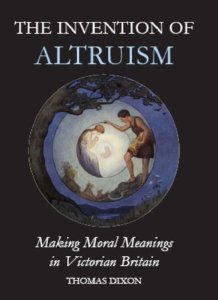

Conceptual history is tool, but it has a major flaw. Changes in words do not change concepts, rather, changes in concepts cause words to be used differently. While expanding beyond text into a semiotic net is a way forward, what this should show those using this type of contextual history is that the concept is the tree upon which signs and words hang, not the other way around. This means there are two options. The first is to do word histories or historical semantics, à la Thomas Dixon (for instance in his 2008 book, The Invention of Altruism), in which words are studied closely as usages are attached, altered, discarded and reinvented. The second is to follow the concept and show how the words and signs relating to the concepts change, adapting and altering as a culture grapples with it. In short, it means separating concepts from signs and language, and thereby ripping the heart out of Conceptual History.

Conceptual history is tool, but it has a major flaw. Changes in words do not change concepts, rather, changes in concepts cause words to be used differently. While expanding beyond text into a semiotic net is a way forward, what this should show those using this type of contextual history is that the concept is the tree upon which signs and words hang, not the other way around. This means there are two options. The first is to do word histories or historical semantics, à la Thomas Dixon (for instance in his 2008 book, The Invention of Altruism), in which words are studied closely as usages are attached, altered, discarded and reinvented. The second is to follow the concept and show how the words and signs relating to the concepts change, adapting and altering as a culture grapples with it. In short, it means separating concepts from signs and language, and thereby ripping the heart out of Conceptual History.

For emotions, this is no bad thing. Word histories can trace the way a word, or even a sign, changed its relationship to emotions over time. The concept first method is particularly useful in affect histories, for example, following the ways in which people attempted to define difficult to express feelings and experiences, but neither are Conceptual History. Some of the tools of Conceptual History may well remain useful to the History of Emotions, such as examining basic concept-semantic/semiotic net relationships in a particular point in time, but it would become a tool in a much bigger type of history: A History of Emotions.

Follow Richard on Twitter: @AbominableHMan

[1] “Introduction (Einleitung) to the Geschchtliche Grundbegriffe“, Trans. Michaela RIchter, in Contributions to the History of Concepts, 6, no.1, (2011) 7-37, quotations at pp. 7, 8.

Fanny H. Brotons

Fanny H. Brotons

1986 as The Foul and the Fragrant. In 1994, Aroma: A Cultural History of Smell by Constance Classen, David Howes, and Antony Synott offered the first comprehensive exploration of the cultural role of odours in Western history and examined olfaction in a variety of non-Western cultures. Both these seminal works, along with Patrick Süskind’s best-selling novel Perfume: The Story of a Murder (1986), were crucial in helping arouse interest in the many ways in which smell informs identity and culture.

1986 as The Foul and the Fragrant. In 1994, Aroma: A Cultural History of Smell by Constance Classen, David Howes, and Antony Synott offered the first comprehensive exploration of the cultural role of odours in Western history and examined olfaction in a variety of non-Western cultures. Both these seminal works, along with Patrick Süskind’s best-selling novel Perfume: The Story of a Murder (1986), were crucial in helping arouse interest in the many ways in which smell informs identity and culture.

Paul Burstow MP was formerly the minister of state for care services, and is head of a commission on mental health at the liberal think-tank Centre:Forum. That commission has just brought out its

Paul Burstow MP was formerly the minister of state for care services, and is head of a commission on mental health at the liberal think-tank Centre:Forum. That commission has just brought out its