This year, I’ve started researching ecstatic experience, from a personal and an academic perspective. One of the highlights of my research has been encountering the work of Ann Taves, a religious studies academic at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of two fascinating books on this area: Fits, Trances and Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience from John Wesley to William James (1999), and Religious Experience (Reconsidered): A Building Block Approach to the Study of Religion and Other Special Things (2010). I have previously blogged about how Taves is laying the groundwork for a more multidisciplinary approach to unusual experiences, which brings together the sciences and humanities. We subsequently got in touch, and I interviewed her for the Centre. Here’s our conversation:

This year, I’ve started researching ecstatic experience, from a personal and an academic perspective. One of the highlights of my research has been encountering the work of Ann Taves, a religious studies academic at the University of California, Santa Barbara, and author of two fascinating books on this area: Fits, Trances and Visions: Experiencing Religion and Explaining Experience from John Wesley to William James (1999), and Religious Experience (Reconsidered): A Building Block Approach to the Study of Religion and Other Special Things (2010). I have previously blogged about how Taves is laying the groundwork for a more multidisciplinary approach to unusual experiences, which brings together the sciences and humanities. We subsequently got in touch, and I interviewed her for the Centre. Here’s our conversation:

How and why did you get interested in researching religious / special experiences?

It goes back to the late 80s. When I was teaching Methodist history, I would discuss the unusual kinds of experiences that early Methodists had, but I didn’t know what to make of them. I was raised in a rationalist, secular family and didn’t have a way to make sense of such experiences. But in the late 80s a friend, who was having very unusual experiences of losing time, was diagnosed with multiple personality disorder. Her experience made me aware that our minds are capable of much more than I had ever imagined.

I took a leave of absence from teaching and spent a long time reading about multiple personality disorder. During that period I came across a textbook [on MPD] that opened with a chapter on shamanism. All of a sudden I had this epiphany where I connected my friend’s unusual experiences with shamanistic experiences and with those 19th-century Methodists having out-of-body experiences. I wasn’t equating them but seeing points of analogy that allowed me to set up a comparison between them . That move opened up an interdisciplinary space which I found tremendously exciting, and which in many ways has been fueling my research ever since.

I took a leave of absence from teaching and spent a long time reading about multiple personality disorder. During that period I came across a textbook [on MPD] that opened with a chapter on shamanism. All of a sudden I had this epiphany where I connected my friend’s unusual experiences with shamanistic experiences and with those 19th-century Methodists having out-of-body experiences. I wasn’t equating them but seeing points of analogy that allowed me to set up a comparison between them . That move opened up an interdisciplinary space which I found tremendously exciting, and which in many ways has been fueling my research ever since.

Your work engages a lot with William James – did that engagement begin before writing Fits, Trances and Visions or during?

I’m pretty sure it was in the initial stages of working on Fits, Trances and Visions that his work became more important to me. It took me about ten years to write that book. The first five years were mucking around trying to figure out what I was going to write. In that period, I spent a lot of time with James, exploring the transatlantic connections.

So while you were writing Fits, Trances and Visions, there was a neo-Pentecostal ‘wave’ happening through various denominations, like the Toronto Blessing. Were you ever tempted to go and check out the modern descendants of fainting Methodists?

The Toronto Blessing, a neo-Pentecostal ‘outpouring’ in the late 1980s

Even though my training is more as a historian than an ethnographer, in my personal practice I’ve gone in and out of a lot of religious movements. In college, I was involved with some of the charismatic Protestant stuff. I wrote my senior thesis in college on the charismatic movement as it was hitting the Los Angeles area in the early 70s. Sometimes I sit back and think I’m an ethnographer who’s gone native way too many times.

So that must have been partly why you were interested in this area?

Yes. Also, as an undergrad, I was a religion major, planning to go to medical school, but also very interested in the psychology of religion.

So you were never a believer? I mean…you didn’t have a tendency towards supernatural attributions?

Well, I entered into a lot of things. I have a great capacity for ‘as if-ness’. I can try things out and see what it’s like from the inside. I’ve never fully stayed in one thing and my secular upbringing seems somewhat intact. I don’t know. I don’t fit categories very well.

I guess I just mean, those sort of ecstatic movements still happen, don’t they, so I wondered if you’re curious about contemporary ecstatic movements.

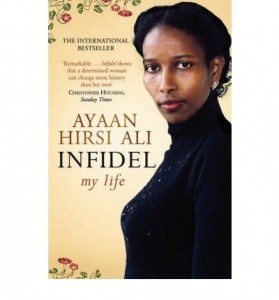

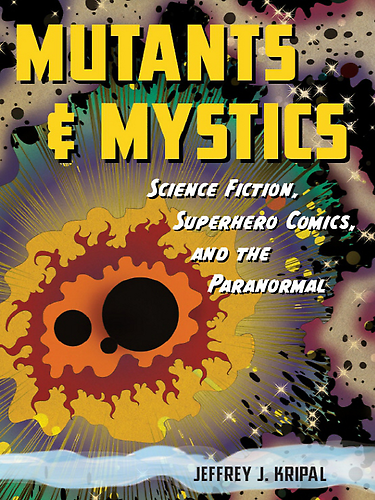

Absolutely. For example, I’ve had long conversations with Jeff Kripal, a scholar of religion at Rice University. He had a very crucial kind of awakening experience – he might call it a Kundalini experience – when he was studying in India. He’s written a whole series of books in which that experience keeps cropping up. As a result of that experience, he’s a big advocate of religious studies scholars paying more attention to unusual experiences and to the possibility of the paranormal. He wrote a history of Esalen, and he’s doing a conference next month bringing together anthropologists of the paranormal where we’ll be discussing how to study such experiences, which a lot of the participants have had to one degree or another. [Kripal is the key-note speaker at a Queen Mary conference on altered states of consciousness in November, by the way.]

Absolutely. For example, I’ve had long conversations with Jeff Kripal, a scholar of religion at Rice University. He had a very crucial kind of awakening experience – he might call it a Kundalini experience – when he was studying in India. He’s written a whole series of books in which that experience keeps cropping up. As a result of that experience, he’s a big advocate of religious studies scholars paying more attention to unusual experiences and to the possibility of the paranormal. He wrote a history of Esalen, and he’s doing a conference next month bringing together anthropologists of the paranormal where we’ll be discussing how to study such experiences, which a lot of the participants have had to one degree or another. [Kripal is the key-note speaker at a Queen Mary conference on altered states of consciousness in November, by the way.]

In Religious Experience (Reconsidered) you suggest we need to drop James’ term ‘religious experience’ and talk about ‘special experiences’ instead. Why?

When we use the phrase ‘religious experience’ we give the impression that there is some kind of experience out there which is always and stably understood as religious. One of the things I became convinced of working on Fits, Trances and Visions is that experiences are unstable both in terms of how they’re understood and the shape of the experience over time. These things are highly malleable. They change as people interact with them, think about what they mean and try to work with them. If people feel they’ve been in contact with something, they may want to interact with the presence. As they try to interact with it, it may take on more distinct form, it may start to say things. Channellers for example often start out seeing something, then internalize it so they become a bodily channel and the entity speaks through them. Experiences can morph over time. Interaction with others over time is crucial to understanding them.

And of course, unusual and ecstatic experiences don’t just happen in religious contexts or with religious attributions. In contemporary culture, for example, there is an overlap between unusual experiences people might consider as religious, and unusual experiences people might consider as aesthetic – my last blog post was about unusual experiences in art galleries, and I’m also fascinated in how ecstatic experiences once found in, say, a Methodist camp-meeting might now be found in a rave or rock festival.

Yes, it’s one of those distinctions we make culturally that we need to move beyond, if we want to work comparatively and across cultures and traditions. We can’t go in with a rigid idea of what’s a religious experience, what’s an aesthetic experience and so on. You should check out the anthropologist Graham St John’s work on psy-trance festivals, by the way.

A scence from a psy-trance festival – image by Sam Rowelsky: http://www.flickr.com/photos/rowelsky/

One thing I’ve noticed is some atheist and humanist thinkers want to reclaim spiritual experience and say ‘this isn’t just for religious people, we also feel awe, ecstasy, wonder and a sense of the numinous’. For example, the atheist Sam Harris is writing a book about spirituality and ecstasy, and he suggests he can feel the same emotion without the same belief or dogma…or even, somehow, without any dogma. I interviewed Brian Eno recently and he argued something similar regarding ecstatic experience (that one can have the emotion without any appraisal). I’m interested in whether one can have an emotional experience without any supporting belief.

I think that’s an important question. If Sam Harris is going to say ‘I’m having an experience of awe and it doesn’t have anything to do with God’, that’s a different kind of experience from someone who says ‘I have an experience of awe and I know this is about God’. Context and interpretation matter. For scholarly purposes, though, we can recognize the basic shape or character that an experience has at a given point in time and identify features that experiences share in common. This allows us to set up comparisons based on the perceived similarity, and then go on to explore the differences.

I suppose lots of people often have ecstatic moments, and for some people those moments just happen and life goes on, while other people try to integrate them into some kind of overbelief.

And in addition, we see others who try to recreate it and get back to it. Within practice traditions, people often seek to cultivate or reproduce a certain kind of experience that they grant a lot of significance.

There are interesting questions around the politics of experience – who controls the interpretation or classification of them into valid or invalid, and who controls access to triggers of ecstasy like drugs. For example, you’ve quoted Barbara Newman’s work on medieval female mystics and the Church’s wary attitude towards them.

Yes, I wasn’t able to elaborate it much in that book.

But in Fits, Trances and Visions there are great stories like the one about the white male preacher sent out to the African-American church, who tries to get them all to calm down and stop dancing, so they just wait for him to leave before getting happy again.

Yes. Part of what I’m trying to do in Religious Experience is lay out a method for comparing experiences that have some feature in common. Then as we can explore the different things that people do with experiences and the way they develop them (or not) over time. In analyzing that we shouldn’t just focus on the individual who has the experience, but on the individual and their interactions with other people and how they interactively assess it. A lot of the time, when people have these unusual experiences they don’t know what to make of them. So they turn to people they’re close to or people who they think have some kind of expertise – that could be a psychiatrist, a minister, a Muslim dream-interpreter, or a paranormal investigator, for example.

It’s ongoing, isn’t it. It’s not like you brand one interpretation on it forever – your interpretation can change over the years.

Bill Barnard talks about an experience had when he was 13 or so. At the time, he didn’t know what to make of it and kept quiet about it, because it felt really special and he didn’t want people to dismiss it. It wasn’t until he was in college, studying Eastern mystical traditions that he thought ‘oh that’s what it was’. I’ve come across that sort of retrospective interpretations a number of times.

Do you think there’s a bias in academia towards naturalistic explanations of unusual experiences? Can academics bring more paranormal or supernatural explanations into the conversation, or is that frowned upon?

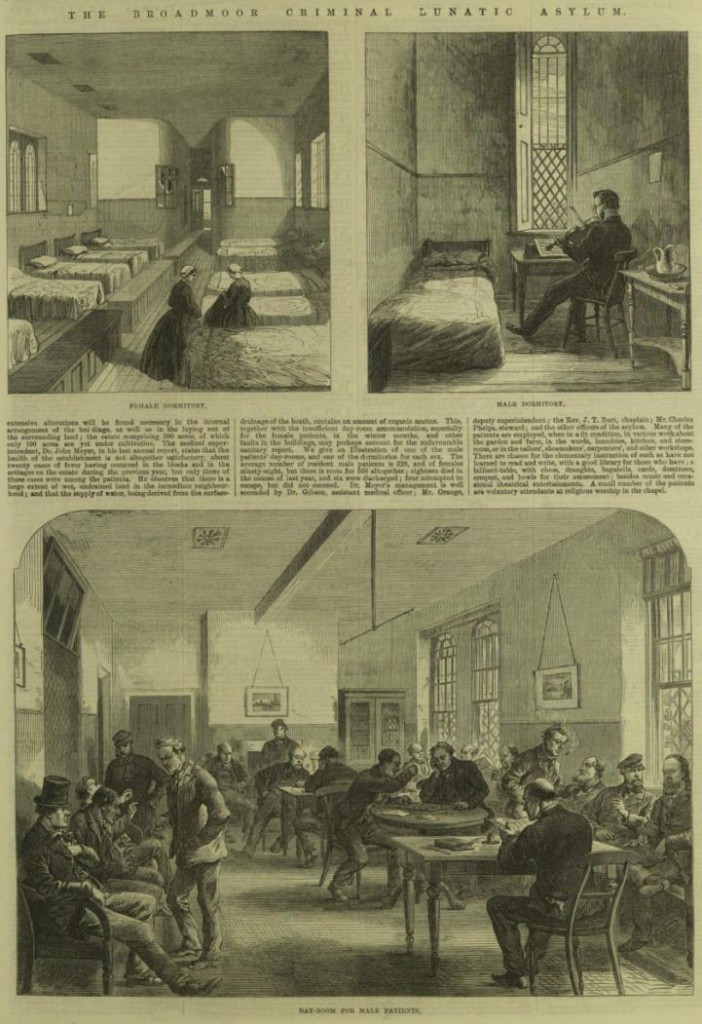

A portrait of Charcot at work in Salpetriere hospital. Ecstatic experiences can be frowned upon in academia.

Sometimes. Within the study of religion, there’s some tension between those who come out of religious traditions and take an explicitly theological approach, and scholars who take a strictly naturalistic approach. The American Academy of Religion, which is the largest body of scholars of religion in the world, is known for being a mix of both kinds of approaches. Some people think scholars should study religion from a strictly scientific and naturalistic point of view; others resist that.

Is there much interdisciplinary work happening between the sciences and humanities on religious / unusual / special experience?

There are a number of things going on. Wesley Wildman, Patrick McNamara and other scholars at Boston University are doing some good interdisciplinary work on religious experience, with a bit more emphasis on the philosophical side of things – they seem to be making the argument that these experiences get us in touch with experiences of the real that are really real. There’s also the anthropologist Tanya Luhrmann’s work – she and I share a lot of interests in common. Her work illustrates the new bridges that some of us are trying to create between ethnographic research and field experimentation. The Templeton Foundation now is putting out calls for research along these lines. [Another interesting collaboration, by the by, is Adam Zeman and Oliver Davies’ work here in the UK, and the ongoing project on Spirituality at the RSA.]

What do you think of ‘neuro-theology’?

My sense is that it’s been overly popularised. There has been some good research trying to look at neural correlates of different kinds of experiences, but often when it gets written up for a more general audience, it winds up making claims that are way too broad and don’t have a lot of nuance or sophistication.

My sense is that it’s been overly popularised. There has been some good research trying to look at neural correlates of different kinds of experiences, but often when it gets written up for a more general audience, it winds up making claims that are way too broad and don’t have a lot of nuance or sophistication.

In Fits, Trances and Visions, you look at various kinds of involuntary experiences, like trances, and how William James, Janet, Myers and others explained them through the concept of the unconscious. Are psychologists still looking at those experiences now, and how do they explain them, if not with reference to the unconscious?

There’s a group of people, including Jeff Kripal, who are interested in the paranormal. And they would argue, and I agree with them, that leaving the paranormal out of conversations about unusual experiences is not a good move. It was very much part of the turn-of-the-century conversations – the Society of Psychical Research was open to a whole range of explanations. That’s one strand of research that hasn’t been well integrated into religious studies or into psychology. One of the articles I’ve been working on is about the International Congresses of Psychology at the turn of the century, where academics were arguing about what experimental psychology was going to be, and formalising the shape of the discipline. I argue that the emergence of the psychology of religion was premised on a narrow definition of psychology and of religion, which excluded the occult, the paranormal, and magic. Doing that ruled out a whole range of phenomena which absolutely should be in the picture. What I’m doing by talking about experiences deemed unusual or special is trying to get all of that stuff back in the picture.

But are you saying the only way to think about involuntary experiences like trances is to bring in the paranormal?

Frederick Myers

Let me put it this way. Pierre Janet was Charcot’s assistant, while Frederick Myers worked with William James. Both used the unconscious to explain hypnotic or trance states. But Janet and Myers had different views of the unconscious. Janet saw it as naturalistic, and viewed his patients’ secondary selves as strictly psychopathological. Myers had a view of the unconscious as the source of both subnormal experiences but also potentially an opening for supernormal or paranormal experiences – including insights or communications that came from beyond the self. James himself left the question open by adopting Myers’ definition of the unconscious, which didn’t have a clear outer boundary. Our experiences didn’t necessarily end with ‘the natural’, in his view. James liked that ambiguity.

That’s interesting. One of the things that Rhodri Hayward of our Centre looked at, in his book Resisting History: Religious Transcendence and the Invention of the Unconscious (2007), is how the disciplines of history and psychology were committed to a model of the self as closed, naturalistic and mortal, and how Myers and others challenged that model – perhaps the self is not closed, not naturalistic, and not mortal.

Yes. There’s a book called Irreducible Mind: Towards A Psychology for the 21st Century. It’s written by a group of psychologists who are all interested in a psychology that incorporates the paranormal – they dedicate the book to Frederick Myers, and to Mike Murphy, one of the founders of Esalen. These are the psychologists and anthropologists trying to resist reducing mind simply to naturalistic psychology. Don’t misinterpret me – I don’t necessarily share all their views, but I’m interested in them.

Could you tell us about the book you’re working on now?

Sure, it’s called Revelatory Events, and I’m working on four case studies – Joseph Smith and the early days of Mormonism, Alcoholics Anonymous, and two channellers – Helen Schucman who scribed A Course In Miracles, and Jane Roberts who channelled an entity known as Seth. What I’m interested in is the role of unusual experiences in the emergence of all four of these movements.

I’m also interested in how Bill W, the founder of AA, was liberated from alcoholism by a religious vision he had while tripping on belladonna. I wrote an article about it in Wired, in fact.

I decided to put AA in towards the end, because I think it will make an interesting comparison to Mormonism. Mormonism plays up Joseph Smith’s experiences, and make him the sole prophet, whereas with Bill Wilson, his experience is downplayed, and actually became a stumbling block for those who were worried that to be in AA they needed to have a sudden, dramatic experience such as Bill’s. So AA very quickly made it clear that such an experience wasn’t necessary.

I decided to put AA in towards the end, because I think it will make an interesting comparison to Mormonism. Mormonism plays up Joseph Smith’s experiences, and make him the sole prophet, whereas with Bill Wilson, his experience is downplayed, and actually became a stumbling block for those who were worried that to be in AA they needed to have a sudden, dramatic experience such as Bill’s. So AA very quickly made it clear that such an experience wasn’t necessary.

AA seems to me the kind of religious movement that William James would really approve of, in terms of being not too dogmatic while also helping relieve a lot of human suffering.

Absolutely. And I also want to mention just finally some of the new work we’re doing. It was interesting that in your blog post on ‘the new science of religious experience’ you mentioned both my work and the work of Dr Emmanuelle Peters at Kings. We’ve just recently got in touch with Peters’ team, who have done some great work on appraisal, and how people appraise unusual experiences. We think that the tools they have developed will be very useful for looking at how appraisals can lead to new religious and spiritual movements.

Peters’ team has also done interesting work on the prevalence of out-of-ordinary experience in the general population, and on how community support groups like Hearing Voices or the Spiritual Crisis Network can help people make sense of those experiences, often more constructively than clinical psychiatrists.

You might also be interested in a project on Durham called Hearing the Voice. Think about Tanya Luhrmann’s work on how the practice of prayer shapes your inner voice, your self-talk. It would be interesting to look at that and compare it to other contexts where people consciously shape and cultivate their inner self-talk, like sport for example. I’m interested in the extent to which sports people are involved in training their inner voice, almost like ascetic monks. They talk to themselves constantly.

Yes. Mike Murphy of Esalen is very big on unusual experiences in sport – one of his books is called Golf in the Kingdom. The Esalen research centre is another place that’s very interested in the intersection of all these things.

And also I guess Mihayli Cziksentmihayli has looked at absorption states or ‘flow’ in creativity, in religion and in sports.

Yes. We have to get out of our boxes because whatever we’re talking about here cuts across a lot of territories.

Yes. It gets tricky though – as you say in Fits, Trances and Visions, ‘the study of religious experience opens up into the study of everything’. There’s no outer boundary!

Exactly.