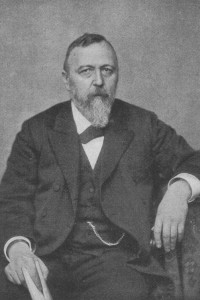

I’ve just re-read William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience, which he gave as a series of lectures in 1902. It is a marvelous book, in which James attempts to take a pragmatic and empirical approach to religious experiences, remaining open to the question of where such experiences come from, and evaluating them by looking at their impact on people’s lives. In other words, he looks at the fruits, not the roots, of religious experience.

I’ve just re-read William James’ Varieties of Religious Experience, which he gave as a series of lectures in 1902. It is a marvelous book, in which James attempts to take a pragmatic and empirical approach to religious experiences, remaining open to the question of where such experiences come from, and evaluating them by looking at their impact on people’s lives. In other words, he looks at the fruits, not the roots, of religious experience.

It’s a pivotal book for my own research. I’m trying to make sense of revelatory experiences, those strange moments when one feels communicated to by some Other, through voices, dreams, visions, intuitions etc. I want to know if we can hold such experiences to critical, rational account, because it seems to me that such experiences can sometimes lead to flourishing, while other times they clearly don’t.

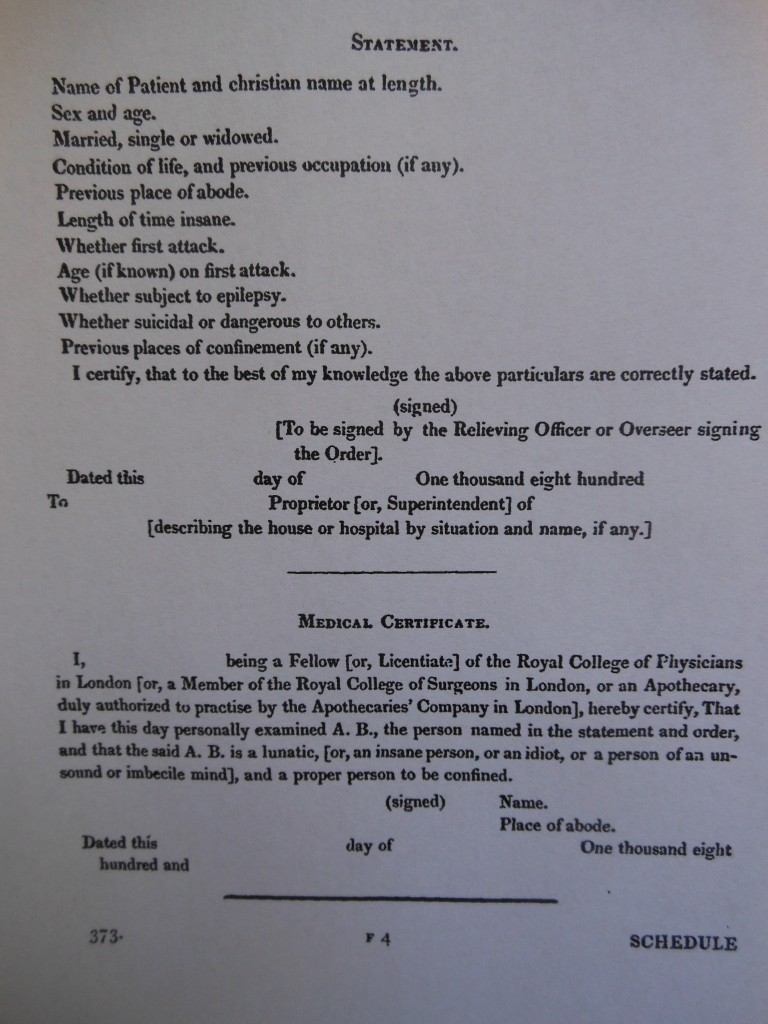

At present, psychiatry more or less entirely pathologises such experiences as ‘psychosis-like symptoms’ and fails to see the positive in them. So it seems to me that western psychology and psychiatry need to return to William James to try to rehabilitate such ‘out-of-the-ordinary experiences’. This is already beginning to happen – this study by a team at KCL led by Emmanuelle Peters, for example, found that such ‘out-of-the-ordinary’ experiences are quite common, and that people who are hospitalised for admitting such experiences typically have a worse outcome than people who find a supportive community like the Hearing Voices Network to help them make sense of and integrate such experiences. Eleanor Longden also has a fascinating story to tell about how she recovered from psychosis by learning to talk calmly to her voices.

James’ work is not perfect by any means but it provides a brilliant platform for a new contemporary exploration of spiritual experience. Let me outline five aspects of his definition of religious experience – four problems with it, and one brilliant aspect of it – before seeing if we can find an updated definition of spirituality.

1) James rightly connects religious experience to the unconscious

This is what I think is really wonderful about James’ approach. It’s where he was a huge inspiration to Carl Jung, Joseph Campbell, and later religious innovators. He declares that the great revolution of psychology is the discovery of various levels of the self, including ‘whole systems of underground life’ beneath ‘consciousness of the ordinary field’. He says: ‘we cannot, I think, avoid the conclusion that in religion we have a department of human nature with unusually close relations to the trans-marginal or subliminal region.’ That is why so many religious leaders were subject to ‘automatisms’ like trances, visions, voices and hallucinations.

James brilliantly analyses conversion experiences with reference to these unconscious levels of the self. New emotions, new beliefs, new attitudes and habits may build up beneath our everyday consciousness, he says, and then suddenly break out into our consciousness in moments of hot excitement. A new self is born, as our personality coalesces around a new centre. What was merely thought before is now known and felt.

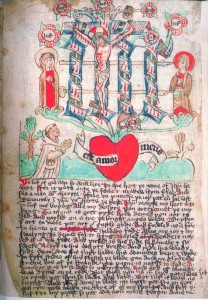

James, like Jung, thinks religious traditions are a useful guide to the underworld of our unconscious

Because such apparently sudden transformations come from the unconscious, it may feel to us as if they come from an external power, something separate and bigger than our conscious everyday self, which we call God. James leaves open the question of whether God is in that broader Self or not. He says: ‘IF THERE BE higher spiritual agencies that can directly touch us, the psychological condition of their doing so MIGHT BE our possession of a subconscious region which alone should yield access to them.’ Some pioneering psychologists, like James, Jung, and Frederick Myers, believed in a higher power or spirit which communicates to us through the unconscious, while others, like Charcot and Freud, didn’t.

It’s interesting to think of conversions in charismatic church services as something akin to electro-shock therapy – they heat up the self, softening its rigid habits through intense emotional excitation, and then zapping it into a new configuration, new habits, a new centre in God. Drug experiences likewise involve a sudden dilation of the self and an opening up to new levels, and they can also involve sudden conversions or switches into new configurations (the founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, for example, was saved from alcoholism by a religious vision while on psychedelic drugs).

2) James mistakenly defines religious experience purely in terms of emotions, and disregards beliefs, dogma and daily practice

James defines religion as a series of passionate experiences. His book explores the most emotional moments in the religious life – moments of mystic expansion, dark nights of the soul, blissful moments of conversion and reconciliation to the Divine. He dismisses theology as utterly secondary to these hot moments of religious passion.

Beliefs, philosophy and theology are trellises around which the sapling of our spirituality can grow

The problem with this approach is that emotions always contain beliefs – even if the beliefs are as basic as ‘God loves me’ or ‘things will be OK’. After such moments have passed we are faced with the task of making sense of them, and turning them into a coherent daily practice, which probably involves turning to older authorities (including written authorities like scripture) to try to cobble together some sort of philosophy or theology as a trellis around which the sapling of our spirituality grows.

Defining religion by focusing entirely on peak (or trough) experiences is like defining marriage by focusing on the experience of falling in love. We should remember that James never himself joined a religion and remained a sort of dilettante in such matters – he’s more interested in religious experiences than the daily religious life. His approach is entirely modern, it seems to me: these days, many of us have occasional spiritual experiences (whether we interpret them as supernatural or natural), but we fail to integrate them into a coherent philosophy or daily practice.

3) James oddly defines religious experience as solitary

His definition of religion as the experiences of ‘individual men in their solitude’ betrays ‘an almost comical Protestant bias’, as Wayne Proudfoot puts it. Religion comes from religio, meaning ‘to bind together’, and many of people’s religious experiences are collective experiences – praying for each other, healing each other, singing or dancing together, worshipping together, discussing scripture or philosophy together, and so on. James make the opposite mistake to Emile Durkheim, who focuses entirely on the communal aspects of religion and its function as the glue for social cohesion. Durkheim (and, recently, Jonathan Haidt) ignores the solitary, individualistic and socially disruptive aspect of religious experience, while James ignores the communal, cohesive aspects of religious experience. A better approach would take both aspects into account.

4) James problematically tries to evaluate religious experiences pragmatically, in terms of whether it leads to human flourishing

James tries to reconcile religion to empirical pragmatism, by looking at its impact on people’s lives. He tries to assess it, in other words, by asking if it leads to human flourishing or not. Does it make a person happy and healthy, does it lead to socially useful things like charitable activity, loving community or great art?

He decides that, basically, religious experience does lead to a lot of human flourishing. He highlights all the healing that religious experiences can cause, looking in particular at the Mind Cure moment, which was a big thing at the beginning of the 20th century. He looks at instances of conversion helping people to kick bad habits like addiction He looks at asceticism, how it has helped inspire people to endure hardships. And he looks at how revelatory experiences have inspired people to new heights of charity, expanding our sense of love for our fellow beings and helping to create a more humane world.

He also looks at some of the more poisonous fruit that religious experience can lead to: excesses of asceticism and self-mortification, or excesses of other-worldly devotion to God. He decides that we need, in an Aristotelian sense, to be moderate in our religious passions, and to use our practical discernment or ‘common sense’ to make sense of such experiences and to decide if a message from God / the subliminal Self should be followed or not.

I am broadly in agreement with this pragmatic approach to religious experience. Revelations need to be held to rational account and to social account. The pastor Pete Greig spoke recently of a friend of his who was in a terrible relationship, and then one day in the bath he heard a voice saying he should marry his girlfriend. His friends, including Pete Greig, thought this was clearly a terrible idea, but the guy decided this was a message from God and must be obeyed. The marriage lasted about a year. I have a friend who suffers from paranoid schizophrenia, who hears voices that give him commands, including that he must always walk on the outside of parking meters. We need to be able to hold messages from the Other to account, as they may not be from God.

But there are two problems with this pragmatic approach. Firstly, James is too generous in his assessment of the fruits of religious experience – religious experience leads to much more poisonous fruits than merely excesses of asceticism, such as violence, demonization of people different to us, pogroms, even genocide. James dismisses this by focusing on individual experiences rather than collective or corporate experiences, and says blithely that evil things like pogroms are really evils of our tribal nature and shouldn’t be lain at the door of religion. But that’s letting religion off too easily. Such evils should be lain at the door of our unconscious – there are dragons down there, as well as treasures, and religions have a historical record of releasing the dragons. Atheist philosophies may also tap into such ‘religious emotions’, such as the millenarian hope for a perfect tomorrow, by the way, and may also ‘inspire’ people to kill others in pursuit of that utopia.

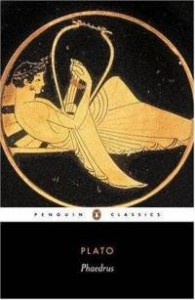

Secondly, while I broadly agree that we should hold revelations to rational account, it’s also the case that sometimes revelations fly in the face of common sense. For example, James says that one of the fruits of saintliness is a sort of reckless charity that seems stupid at the time but which is vindicated through its salutary effect on human history and culture. How would Jesus’ message hold up to the ‘common sense’ of the time? Or Socrates? The point about revelations is that they are often the eruption of something radically new and scandalous. They don’t necessarily fit with common sense – they may challenge it. As John Wimber, pioneer of the Vineyard church movement, put it: ‘If there is ever a choice between the smart thing to do and the move of the Holy Spirit, I will always land on the side of the Spirit.’

James’ pragmatic approach to religion needs to grapple with Kierkegaard, who pointed to the story of Abraham and Isaac to illustrate the essential irrationality of religious faith. If God told us to kill someone, should we obey Him? I personally think that James is right and Kierkegaard is wrong: Abraham should not have obeyed God. This is not a purely theological question, by the way – people suffering from paranoid psychosis often hear voices telling them to kill other people. We need to find a way to reason with the commands that come from our unconscious self, and not be fundamentalist in our relationship to them.

5) James wrongly tries to separate religious experiences from similar but non-theistic experiences

James defines religious experiences as experiences of man in relation to ‘whatever they consider divine’, and further defines that as a belief in an unseen metaphysical order with which we can have a relationship. However, people have experiences very similar to those he describes – feelings of expansion, awe, wonder, surrender, ecstasy – without believing in an unseen moral order or Almighty Being.

To take five examples of such ‘non-supernatural spiritual experiences’:

a) Art: Jesse Prinz has discussed how art makes him feel ‘wonder’, how he goes on ‘pilgrimages’ to cathedral-like galleries and feels expanded; likewise, Brian Eno has spoken of how music creates a feeling of surrender similar to religious ecstasy; the music journalist Peter Guralnick has brilliantly described soul music as ‘secular ecstasy’. I’ve written about dance music, and the experience of dancing together, as a spiritual experience. Clearly, as Roger Scruton has discussed, art gives us access to emotional experiences which people used to feel mainly through religion.

b) Sex: James tries to dismiss the Freudian suggestion that religious experiences are really sublimated sexual experiences. He counters that religious experiences ‘have nothing to do with’ sex. But that’s clearly not true – just this Sunday I heard a lady at church having an encounter with Jesus that sounded very much like an orgasm. Religious ecstasy is not the same as sexual ecstasy, but they are similar. Our love-lives likewise involve sudden conversions, sudden expansions into new worlds, and ecstatic surrender to the Other. DH Lawrence beautifully described this sort of sudden unfolding into new selves through sexual experience in books like The Rainbow, which for me was a very important book in my nascent spirituality.

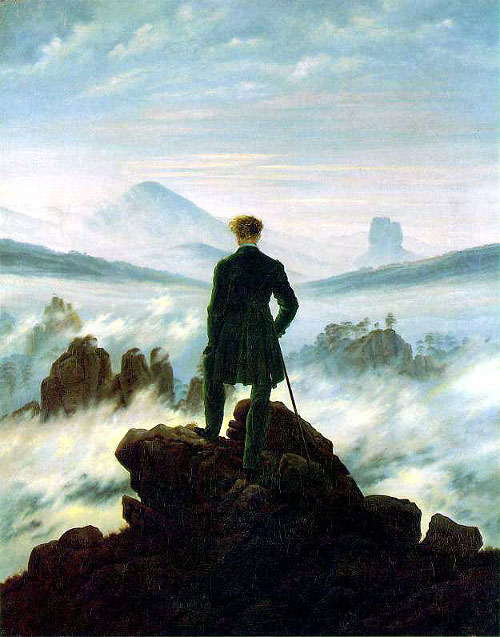

c) Nature: James examines moments where people feel close to God in Nature, like Emerson or Thoreau in their forests feeling connected to the Over-Soul. But people can also have intense experiences of awe and wonder in nature without believing in God. Atheists might argue that watching a David Attenborough documentary, or Carl Sagan’s Cosmos, is a spiritual experience, or they might feel a sense of peace and awe while trekking or sailing. Epicureans would say that star-gazing is a sort of spiritual exercise for them, although they were materialists. A lot of the popularity of walking books like Ross MacFarlane’s The Old Ways come from people’s desire for spiritual experiences in nature – whether they believe in God or not.

d) Sport: In discussing the unconscious, James talks about those moments when a player switches from his conscious everyday self to a more unconscious level and ‘the game is played through him’. Modern psychologists would call that flow. It can feel wonderful and spiritual. A famous instance of such a moment is Liliam Thuram scoring two goals in the World Cup Semi-Final, a game he has no memory of playing. The coach of the French team says he was in ‘some mystical state’. More broadly, playing sport and supporting a team gives us a sense of collective endeavour in which we’re lifted out of the individual self and surrender to a collective identity. Playing together, we feel passionately connected to our team-mates. We also go through dark nights of the soul (i.e English football in the last 40 years) and moments of ecstatic deliverance (ie British tennis in the last year).

e) War: As Chris Hedges has written, war is a force that gives us meaning. It’s dark to admit it, but many people find war a spiritual experience – they’re lifted out of their individual self and surrender to a collective identity, they feel passionately fused to their comrades, even mystically connected to them like hunters in a pack. They get a deep sense of heroism and righteousness from their sacrifice. But, like drug experiences, war can also wound us at profound levels of our consciousness, and reset our personalities in new and darker configurations.

f) Drugs: As James explores in the Varieties, drugs take us beyond ordinary consciousness and open doors to deeper levels of consciousness. He says: ‘I know of more than one person who is persuaded that in the nitrous oxide trance we have a genuine metaphysical revelation’, and if he’d lived longer he’d no doubt have written interestingly on psychedelic experiences, as Aldous Huxley would do. As Sam Harris has recently insisted, we may have very ‘spiritual’ experiences on LSD, MDMA, DMT or other drugs, without believing in a higher power or invisible moral order.

f) Drugs: As James explores in the Varieties, drugs take us beyond ordinary consciousness and open doors to deeper levels of consciousness. He says: ‘I know of more than one person who is persuaded that in the nitrous oxide trance we have a genuine metaphysical revelation’, and if he’d lived longer he’d no doubt have written interestingly on psychedelic experiences, as Aldous Huxley would do. As Sam Harris has recently insisted, we may have very ‘spiritual’ experiences on LSD, MDMA, DMT or other drugs, without believing in a higher power or invisible moral order.

So we need to broaden the investigation of such experiences and recognise that one can have spiritual experiences without believing in ‘the Divine’.

6) Towards a better definition of spiritual experience

Here’s my attempt towards a better and more comprehensive definition of spiritual experience, which can incorporate both materialist and animist conceptions.

a) Spiritual experience involves an expansion beyond the confines of ordinary consciousness, into a broader Self, a dilated Self, in which the walls between deeper levels of consciousness become porous.

b) Spirituality typically involves an optimism that, although there are dragons in the unconscious, there are also treasures. The treasures of the unconscious include healing power, imagination, and moral sentiments like wonder, awe and ecstasy. If you’re materialist, you can understand the healing power as being the power of suggestion and hypnosis.

c) Our encounters with these deeper levels of the Self are mediated and shaped by beliefs and culture. Religious traditions, and religious beliefs, practices, art and institutions, are storehouses for explorations of this broader Self, and they shape our experiences in different ways. There are toxic aspects to just about every religious tradition, moments when the dragons of the unconscious take charge and lead to intolerance and violence. Nonetheless, religious traditions can also lead us to the treasures of the unconscious. These traditions are there to be used, like Virgil in the Divine Comedy, as guides to the underworld. But they have to be used skillfully.

d) Our broader Selves are connected to one another, and in moments of spiritual dilation we have a deeper sense of this interconnection with others. You can interpret this connection naturalistically – as a intuitive sympathy that can arise between people (between musicians when improvising or team-mates playing sport for example) – and put forward an evolutionary explanation for it as an adaptation that improved hunting and social bonding. Or you can interpret it in animist terms, as William James or Rupert Sheldrake do: we are connected to one another through non-material networks of sympathetic consciousness, which is why prayer works, and why a prophetic word for one person can come to another person.

Theists would then go one further and say

e) Our broader Selves are connected to God, and draw their power from God, and within our broader Selves is an immortal soul.

At which point of course materialists and animists part company. But there are still many steps on which I hope materialists and animists can agree.

In the meantime, here is a song I wrote a few years back, exploring some of these same questions of the difficulty of knowing if a message from ‘beyond’ is from God, the Devil, aliens, the Unconscious or what-have-you. It’s called Messengers.