This is an interview I did with Professor Martha Nussbaum back in 2009, for The Stoic Registry (a web magazine for Stoics. No, really!) Professor Nussbaum, who is the Ernst Freund distinguished professor of ethics and law at the University of Chicago, is one of the most important philosophers of emotion today. She’s done a great deal to revive academic and general interest in Hellenistic philosophy and virtue ethics, and to show their relevance to the contemporary politics of well-being, through books like Upheavals of Thought; Cultivating Humanity; and The Therapy of Desire, and through her work with Amartya Sen on the ‘capabilities approach’ in development economics.

This is an interview I did with Professor Martha Nussbaum back in 2009, for The Stoic Registry (a web magazine for Stoics. No, really!) Professor Nussbaum, who is the Ernst Freund distinguished professor of ethics and law at the University of Chicago, is one of the most important philosophers of emotion today. She’s done a great deal to revive academic and general interest in Hellenistic philosophy and virtue ethics, and to show their relevance to the contemporary politics of well-being, through books like Upheavals of Thought; Cultivating Humanity; and The Therapy of Desire, and through her work with Amartya Sen on the ‘capabilities approach’ in development economics.

So you began your academic career in Harvard in 1975…

Well, I started my graduate career at Harvard, but I don’t regard my academic career as having started there, I regard it as starting in high school. I was already working on the same problems when I was 16 that I am now.

For example?

I was already thinking about the nature of emotions, their role in ethical life. I did quite a lot of writing on the tension between the aspiration to justice and the aspiration to love in individuals. I wrote a long play on that, it was actually about Robespierre and the French Revolution, but the main theme was love versus justice.

When did your relationship start with ancient philosophy?

It was probably when I was around 14. We were studying ancient Greece, and I was given a special assignment – the teacher thought several of the more ambitious students could write essays on tragic and comic poets, so I got going on Greek drama. I was also doing a lot of acting in those days.

How much would you say has changed in terms of the level of interest in Hellenistic philosophy, in academia and among the general public, since the beginning of your career?

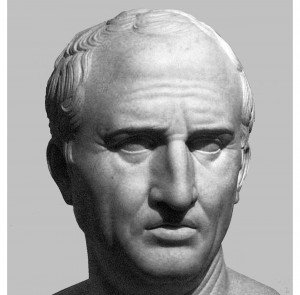

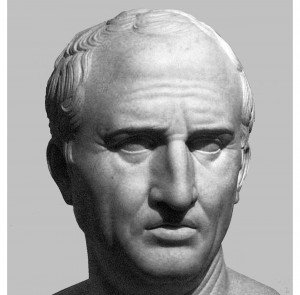

You need to look at the longer trajectory. Hellenistic philosophy was absolutely central to the education of any cultivated person in Europe and North America from around the 17th to the late 19th century, so you did probably read some Plato and Aristotle, but you were much more focused on Roman authors. Lucretius, Seneca, Marcus Aurelius, and Cicero above all, were authors that really shaped the thinking of a lot of public life in not only continental Europe but Britain and the US. Stoicism had an enormous influence on the Founding Fathers, for example.

So the question is really: why did it go out of fashion? And it’s really because of the influence of Hegel and Nietzsche. They were taken as guides, and they made Plato a much more central figure. People were also focusing more on Greece than Rome, and of course the Hellenistic Greek texts are just lost, they’re fragments, so people forgot about Hellenistic thinkers.

There was a huge gap in the world I grew up in graduate school. Everyone was reading Plato and Aristotle, they thought that was absolutely central, and there was no study at all of Hellenistic philosophy. People didn’t even think you had to learn Latin to do ancient philosophy, because it was clear to them that Roman philosophy was not worth studying. I was actually very lucky that I got my PhD in classical philology and not classical philosophy, because it meant I had the equipment to study a lot of the classic works of Roman philosophy — including the poetic works of Lucretius and Seneca.

The revival of Hellenistic philosophy was very self-conscious. It was started above all by a group of philosophers in the generation before mine, led by Richard Sorabji, Miles Burnyeat and Jonathan Barnes, who decided ‘well Plato and Aristotle have now been exhausted, they’ve been mined for their philosophical significance, we should move on and do something where we can make a creative contribution’.

So they got people together to have these meetings called Symposium Hellenisticum, and I was lucky enough to be invited to the first one, in Oxford. It was around 1980 or just before. They published a collection of essays shortly after, called Doubt and Dogmatism, which is quite a famous book. Then every three years they held a similar meeting. I didn’t give paper at the first one because it was on epistemology, which is not my thing. But the third symposium was on ethics, and I did give a paper, and was on my way, because I decided to write book about it.

So they got people together to have these meetings called Symposium Hellenisticum, and I was lucky enough to be invited to the first one, in Oxford. It was around 1980 or just before. They published a collection of essays shortly after, called Doubt and Dogmatism, which is quite a famous book. Then every three years they held a similar meeting. I didn’t give paper at the first one because it was on epistemology, which is not my thing. But the third symposium was on ethics, and I did give a paper, and was on my way, because I decided to write book about it.

Would you say there has been a revival in the general public’s interest in Stoicism?

The humanities curriculum has still not internalized it. Look at the typical Great Books curriculum, which is two years of liberal arts study. That’s where a member of the general public would make contact with Stoicism, but the curriculum still doesn’t reflect the revival of interest in Hellenistic philosophy, it’s still focused very strongly on Plato and Aristotle, and then it might go quickly over Augustine and Aquinas, but sometimes it still leaps straight over to Descartes. So there’s not very much Hellenistic philosophy in the average Great Books curriculum. They don’t focus on Rome in general, and that’s what you have to do if Hellenistic thinkers are to be read. Of course, Lucretius is always loved, so he’s an exception, but that’s because people think of him as a poet rather than a philosophical thinker.

As for Seneca, part of the reason there’s a lack of interest in Seneca is the translations are of a very uneven quality. Right now at the University of Chicago Press, there’s a project to make a complete set of new translations of all the works of Seneca. There’s a terrific team of experts lining up to translate all the philosophical works, the literary works, the tragedies and so forth. My own translation is of the Apocolocyntosis [Seneca’s satire on the death of Claudius], which is the only funny Stoic work… maybe it’s not Stoic, but it’s by a Stoic.

In your book, Upheavals of Thought: The Intelligence of Emotions [2001], you describe your position as neo-Stoic…

I’ve got to correct this – there are two parts to the Stoic view on emotions, the descriptive part and the normative part. What I call neo-Stoic is the descriptive view of what emotions are like, but I certainly reject the normative view.

So what do you think Stoics got right and wrong?

Are we talking about the descriptive view?

Let’s start off there.

With that, I think they have a very powerful position about the role of judgments of value in emotions, which has now been amply supported by psychological research into the emotions, and i show that convergence between Stoic philosophical analysis and modern psychological analysis, which focuses on what psychologists call appraisals, that is, evaluations and their role in emotions. That part the Stoics got brilliantly right, and a lot more detail about particular emotions they also got right.

What you need to do, to make it a defensible philosophical view, is to correct their view that animals and small children don’t have emotions. That’s not correct, so you have to revise that view so that emotions still have a cognitive / evaluative character but it’s the sort of cognitive character that animals and children could have.

Secondly, the Stoics are also not very sensitive to cultural variation in emotion, so you have to learn from anthropology and put that into the neo-Stoic view.

And finally, because they didn’t think you had any emotion until you were sixteen, which is a very implausible position, they didn’t care about development and how that influences emotions, and we do have to care about how emotions develop from infancy through childhood into adulthood. So we have to draw on developmental psychology and psychoanalysis.

So can you combine the Stoic cognitive model with a more psychoanalytic model, or are they contradictory?

It depends which psychoanalytic view you use. If you use the view that the goal is always pleasure, then it’s much harder to make a connection. But if you use the view from objects relations theory, according to which children have complex cognitive attitudes to objects, such as anger, grief and envy, that sort of view that you get in Klein or Winnicott meshes very nicely with the basic way that Stoics view the world, and it also make sense of the fact that children do have emotions.

Upheavals draws some great parallels between Stoicism and modern psychology and neuroscience. How rare is that? How much of a dialogue is there between classical academia and modern psychology?

If you’re talking about classicists, it’s an individual matter. If you’re talking about philosophers working on emotions, it happens all the time. You wouldn’t think of publishing something on the emotions without becoming at least aware of what’s going on in neuroscience. Sometimes philosophers do it too often. They think neuroscience solves all our philosophical problems, whereas I think it gives us helpful hints, but doesn’t replace the need to do hard philosophical work, and also doesn’t replace the need to go back to developmental psychology and psychoanalysis, which some neuroscientists don’t like at all. So you need a judicious sense of what it can solve and what it can’t.

So what did the Stoics get particularly wrong?

I already told you three big things that are wrong in the descriptive view. Turning to the normative view, Stoics think the correct attitude is that nothing is worthy of serious concern except our rational nature, nothing outside of us, not our political culture, not our friends or our children, none of that is really worth serious concern, so we shouldn’t get upset when bad things happen to them. It’s hard to argue with that because it’s a very complete view and internally consistent in most ways.

So if we produce an argument that will shake a modern Stoic, it needs to show something of importance to the Stoics themselves that the Stoic view can’t explain. I try to show certain things Stoics want to say – for example that we should care about our country and should be committed to defending it – which contradict their view on externals, so in the end they can’t defend their theory. It’s not simple, you need to take a long time to show that, but I think you can show that, even on its own terms, it’s not entirely successful.

So the Stoic position that all externals are indifferent is untenable?

Cicero: bad Stoic, good human?

The Stoics think you should never mourn, for example. Cicero reports that a good Stoic father says, if their child dies, ‘I was always aware that I had begotten a mortal’. Now, Cicero is one of my favourite thinkers of all time, and I find it very interesting to look at his letters when his daughter died. Just before she died, he had been writing typical letter of Stoic consolation to a friend who had lost a child. But when his own daughter died, he was absolutely devastated. He says to his friend Atticus again and again, ‘I can’t do normal things’. Atticus says ‘this is not seemly, not fitting, you should not mind this so much’, and at one point Cicero says ‘it’s not only that I can’t go about my normal business, it’s also that I don’t think I ought to’.

So he made un-Stoic judgments about both his daughter and the Roman republic. He lost his life trying to save the Republic. If he hadn’t stayed in Rome so long trying to criticize Mark Antony, he wouldn’t have been assassinated. He lived his life for both these things – his daughter and the Republic – and both were lost. What I find admirable is that he really wrestled seriously with the norms of Stoicism, and saw that they could help us correct an inappropriate kind of worldliness – he saw a lot of people go wrong because they were too ambitious, too competitive, too attached to worldly goods. But about the things we really love, and rightly love, we shouldn’t be Stoic.

So even if we don’t accept the Stoic view of externals, we can still use Stoic methods of therapy?

The therapy they have in mind is that you can’t really improve your life without understanding what’s worth valuing and what isn’t. It would have been better if everyone learned all this in the first place, but since, according to them, people live in a highly corrupt culture, they don’t learn right values, so they have to be given therapy, which consists in weaning them away from money, status, competitive goods of all sorts, and this will undo the damage of anger, jealousy and so on. All of that seems reasonable; it’s only when they take it so far that they say we should lose love of children, family and so on. There I part company with them. Bu it doesn’t mean their methods of weaning people away from unwise values is useless.

In Upheavals, you argue that Stoics are part of what you call an anti-compassion tradition, as opposed to a pro-compassion tradition. Could you unpack those ideas a bit?

Sure. When people read figures like Nietzsche, who say you shouldn’t have pity, they read that it means you should be cold and hard-hearted. That’s not it at all. Nietzsche tells us he’s following a whole slew of people like Seneca, Epictetus, Kant. These people think that what you rightly value is your own good will and rational purpose, and that external things shouldn’t upset you so much. And then they say ‘OK, if you yourself are not deeply upset when you lose money or status, then you shouldn’t pity or have compassion for someone else who loses those things. If you think you shouldn’t be upset when you lose a child, then when someone else loses a child, you shouldn’t feel compassion’.

Marcus Aurelius says, if someone is upset, and you know they have wrong values, you can treat them the way an adult treats a child – you can console the child, while understanding that the child is upset over nothing. That’s the Stoic view. In other words, you have to be consistent. You can’t say ‘I’m going to get rid of anger, jealousy, hatred, but I’m going to keep compassion, because it’s so nice’. No, what they say is, the best thing to do is get rid of your unwise attachments to externals, so you won’t feel compassion, but you also won’t want to hurt people, or to retaliate against them. You will be detached. So Seneca writes to the young emperor Nero on mercy, saying you should be gentle and merciful, but in the middle of the letter is an attack on compassion. Compassion is this soft thing where you care too much about what’s out there. And they think in that is the seeds of anger, jealously and ultimately cruelty.

It seem to me that Stoics’ problem with emotion is it is either attachment or aversion, either a running towards or a running away from something. But could we argue that compassion could be something more Buddhist, that could not involve attachment or aversion, and rather bean attitude of disinterested concern, which we could integrate into a modern Stoic approach?

Sure, you could. It depends how you define it. Some people do define it like that. But then it’s not really an emotion at all, because it doesn’t involve the idea of a deep attachment to an external object and a mental upheaval about the fortune of that object.

And it doesn’t necessarily involve the judgment ‘this shouldn’t have happened’…

Exactly, or the idea that this person has suffered some important damage. No, you’re supposed to think these things really aren’t that important. But you can still have an attitude of concern, that’s right.

I loved your analysis of Sophocles’ Philoctetes in Upheavals. You made a dichotomy between Sophoclean tragedy and Stoicism, saying that Sophocles teaches us compassion for the wretched, like Philoctetes, while Stoicism teaches a more detached respect for our inner integrity. But could you argue there’s a link between Sophocles and Stoicism, in that Stoicism could be seen as the end-point of tragedy? It’s the point the tragic hero reaches at the end of their journey. For example, Oedipus reaches an end point at Colonus, a point of heroic passivity and endurance, so that whatever the gods of nature send him, he can endure. And by that point he has achieved a sort of divine oneness with nature. And that’s what Stoics are trying to achieve, a oneness with nature and a heroic endurance.

Sophocles’ Philoctetes: an optimistic tragedy

You’re on to something important. I’d say that’s only true of Sophocles among the tragedians, that you find this attitude that the hero may actually transcend the vicissitudes of human fate, and it’s particularly true of Oedipus at Colonus, so you picked the right play. I don’t think it’s really in Philoctetes at all – in that play, there’s a tremendous joy and celebration that he will be cured and the war won. So we’re not deflected from the real world, we’re returned to it, with the right outcome. And likewise in Antigone, there’s a sense of terrible loss and tragedy all around, and no sense that this is mitigated by anything else. So I think Oedipus at Colonus is the closest thing you get to Stoicism in ancient tragedy. And what that shows is that traditional Greek religion had in it elements that Stoics mined for their own view of Zeus and the nature of universe. Which is interesting, because it shows that their view didn’t come out of nowhere.

But could you say that there is a Stoic element even in Philoctetes: towards the end of the play, he can’t go to Troy because he can’t get over his feeling of alienation and resentment, then Heracles appears and says ‘there’s a cosmic plan, and you going to Troy is part of it’. That realisation of a divine providence is what enables Philoctetes to accept his lot. It’s like Hamlet realising there is a divine providence, and accepting his role in it. Isn’t that moving towards the Stoic idea of the Logos, and of accepting your lot in the Logos?

Well, I think it’s quite right that Philoctetes is supposed to go back and play his part, but notice he does it on the condition that he will be relieved from pain, and given great glory, so all the worldly goods are not undermined. It’s not a sacrifice. And you represent Heracles one way, but in fact, Philoctetes is won over because it’s his friend making the appeal, and he trusts his friend, not because there’s a grand cosmic scheme. The main thing is it validates rather than undermines the importance of worldly goods.

Turning to your 1997 book, Cultivating Humanity: A Classical Defense of Reform in Liberal Education. Do you think Stoic techniques of learning to control our emotions should be taught in schools?

The part of Stoic therapy I would like to focus on is the Socratic part , the commitment to self-examination, the relentless scrutiny of traditional values. That’s what I appropriate from the Stoics. The part that says ‘now we can use this to go into people’s emotional lives’…I’m not sure that’s appropriate in a university, it’s more appropriate for small children. The other thing I’d want to appropriate is the Stoic sense of the whole world as a series of concentric circles, and that we should become increasingly aware of the broader world to which we belong. That you really can teach in university curricula, you can talk about the world economy, about different world cultures, different world religions and so on. So that’s a very important thing we can borrow from Stoics.

The Stoic idea of cosmopolitanism?

Yes. We’re citizens of a whole world order. We’re not just members of one family, town or nation, but of the whole world. We’re increasingly interdependent on important issues such as the environment, so there are now even stronger reasons for seeing oneself as cosmopolitan than there were in the days of the Stoic. We can’t escape from the fact that what we do affects lives on the other side of the world.

You’ve written that the goal of political society is to enable citizens to search for the Good Life in their own way. Do you think the state has any role in terms of giving guidance as to what constitutes the Good Life?

I’m in strong agreement with John Rawls that the state has to show equal respect for all different reasonable comprehensive views of the good human life. The only way can do that is via the principle of non-establishment, which means no particular religious or comprehensive ethical view should be the basis of political principles or statements. But we can have a partial ethical view that’s the basis of our political judgments, so we can all overlap on that and speak together in terms of that, because after all our political principles themselves have a moral content.

So what would that involve? Ideas of equal respect, support for human needs, human rights and so on. So there’s a political part of the good human life that we can talk about and that the state certainly should persuade people about. So, for example, last Monday the university closed for the birthday of Martin Luther King. It does not close for the birthdays of racists. Having a national holiday for King, and not for racists, is a form of public persuasion, but it’s right, because racial equality is at very core of the political conception that we all share, whether Protestant, Catholic, atheist, Hindu or what have you.

What about the idea that you find in Stoics and in Martin Seligman [founder of Positive Psychology], that the state and state schools can provide some guidance as to how to find eudaimonia?

Martin Seligman, founder of Positive Psychology

Well, eudaimonia is a contested concept. What the state can do is provide some comparative studies of different traditions, and maybe show some things such as ‘if you want to achieve the following, this is how go about it’. But to advocate one particular comprehensive concept of eudaimonia, whether religious or secular, a public institution shouldn’t do that.

But certainly, in a philosophy course, you can try to show what considerations might make one conception more attractive than another. And when I teach criticism of utilitarianism, that’s what I try to do. But if I was president or a supreme court judge, I would never stand up and say ‘I think utilitarianism is an impoverished world view’. I would focus on the political conception we all share.

Is Positive Psychology going too far down one particular road, of advocating one definition of eudaimonia and then propagating it?

It’s not intended to be political, it’s for people’s personal lives. I’ve been talking about limits on political speech.

But it is taught in schools.

Is it?

Yes. In the UK, for example, the government is considering putting it into the national curriculum.

Huh…Well, it isn’t here, but I guess I would be troubled by that. Seligman is a lot more subtle than most of people who talk about happiness. He has philosophical training, and asks questions about what it really is, he’s pluralist about different religions, so it’s much more open to contestation than many simpler views. But i still think it’s too determinist. The state should not be telling you how to live your life beyond a certain core of political principles. The only thing about Seligman is he thinks we should be happier, that we’re too sad. But I actually think, certainly in the US, that people should be a lot sadder than they are. The reason they’re rather jolly is they don’t think about the suffering of others, they don’t think about the injustice suffered by others. I want to raise the level of sadness and anger in my students rather than diminish it.

You’re an expert in therapeutic techniques in Stoicism, Epicureanism, Scepticism, Platonism and other traditions. Are there ones you’ve found particularly effective or ones you’ve used in situations in your own life?

Well, when I observe my life, I think, ‘How is what I’m going through here related to these views?’ You can see that in Upheavals, where I talk about my mother’s death. Sometimes when I get upset about some temporary thing, I do think ‘you know how you characteristically over-estimate the seriousness of this’…But I’m not sure whether I needed to read the Stoics for that, or whether I always knew it. The parts of Stoicism that appeal to me are when they tell you to get rid of excessive attachment to money and reputation, but that doesn’t happen to be my problem. My upheavals come from attachment to particular people or politics, and that’s the part where I reject Stoicism. So that’s why I don’t find myself using Stoic therapy.

Some of the leading writers on Stoic thought at the moment are women – yourself, Julia Annas, Nancy Sherman. Does that dispel the view that Stoic values are somehow ‘masculine’ values? Is that a wrong view, or even a sexist one?

Probably. I don’t think any one view of values is masculine or feminine. The Stoics didn’t either: they wrote treatise on how the virtues of men and women are the same, and they defended complete equality of the sexes in their ideal city. It’s what Mary Wollstonencraft observed in her critique of Rousseau: people put up a stereotype of women as highly emotional or sentimental, but in fact just it’s just a stereotype. They can be just as rational. And of course, Mary herself was deeply influenced by Stoic thought.

Martha, thanks very much for your time, it’s been a very interesting talk.

Thanks to you, I’ve enjoyed it.

![]()