<When Dr Robin Carhart-Harris finished his masters in psychoanalysis in 2005, he decided he wanted to do a brain- imaging study of LSD to see if he could locate the ego and the unconscious. That might have seemed an impossible dream, considering he had no neuroscientific experience and there had been no scientific research into psychedelics in the UK for over three decades. And yet that’s precisely what Robin has done. We went to Imperial College’s experimental psychology department to meet the 33-year-old whizzkid of psychedelic research.

How did you get into psychedelic research?

It all started when I was studying psychoanalysis at Brunel University. I was in a seminar where the seminar leader raised the different methods for accessing the unconscious mind. It seemed as though the methods used by psychoanalysis were very limited – free association, dreaming, hypnosis, bungled actions, slips of the tongue. They never really convinced everyone.

So I thought if the unconscious is real, could drugs reveal it? I must have had psychedelics in mind. Then I found that there was a book by Stanislav Grof called Realms of the Human Unconscious: Observations from LSD Research, it was a light-bulb moment really. I realized there is all this literature from the 1950s and the 1960s, and the rationale was the drug lowered ego defences such that you could gain privileged access to the unconscious mind. Especially in the early days, that was the idea – that people on LSD might get spontaneous insights into memories or relationships that are causal of whatever symptoms they have. So that’s how my interest started.

What did that first phase of psychedelic research establish?

Unfortunately, I’d say it established nothing. To establish something, you need a robustly designed study, with outcomes that are valid and replicable. A lot of those ingredients were missing. It was certainly highlighting the unique potential of psychedelics.

How long did that phase of research last for, and why did it stop?

Was Timothy Leary responsible for the 30-year hiatus in psychedelic research?

The first English language paper on LSD was in 1950, that was by a couple of Americans. Then the 50s was a busy time, by 54, 55, there were a significant number of papers in the UK, Europe and elsewhere. It peaks around the late 50s. By the time we hit the 1960s, the drug has crossed over and is being used recreationally. So that’s the period of controversy, with negative media reports on LSD, and individuals like Timothy Leary becoming a kind of figurehead, and saying arguably irresponsible things.

I suppose it did have a huge cultural impact.

Yes. One way to look at it is that Timothy Leary’s loud mouth turned a lot of people on to LSD. However, it also turned off the legitimate scientific research.

Can you blame Leary alone?

It would be easy and unfair to blame one individual. People do. But it’s probably unfair. He was stoking the flames. People were saying ‘tread carefully, don’t spoil the party’. And his vision became something other than scientific research, it was about a social and psychological revolution. People were taking LSD without sufficient knowledge of its effects or sufficient caution. So LSD became illegal in 1967, and the illegality made it so much harder to do research.

But there was still some research in the 70s and 80s?

Not really. It’s just barren, in terms of high-end research. In the US and UK it entirely dried up.

When did it restart?

The first modern human study was I think in the mid 1990s, by an American researcher, Rick Strassman. He had a simple study where he gave people DMT (from ayahuasca) intravenously, and he reported on the effects. He had a larger grand theory, that DMT occurs spontaneously in the brain and is responsible for religious experiences. But the study was quite simple. What was odd was he didn’t really do many more studies after this.

But then Franz Vollenweider, who is a Swiss psychiatrist and pharmacologist, started doing research with psilocybin (magic mushrooms), and he did some interesting brain-imaging studies of the effects. People started to consider the potential therapeutic benefits of psychedelics again – there was an early study looking at the impact of psilocybin in OCD. And since then there’s been a psilocybin study for reducing anxiety in terminally ill patients.

Was that Roland Griffiths’ team at Johns Hopkins?

Roland Griffiths of Johns Hopkins Medical School

No that was Charles Grob at UCLA, although Roland is doing this too now. However, Roland Griffiths’ big papercame out in 2006, and he reported on giving high doses of psilocybin to healthy, psychedelically naive people, who’d never tripped before, and lo-and-behold, they had the experience of their lives. It was a very clever study, because it communicated to the man in the street, who doesn’t know anything about psychedelics, that these are drugs that can produce experiences that are among the most meaningful in your life, comparable to things like childbirth for example.

Has there been research on using psychedelics to treat alcoholism?

Yes, there is American research on using psilocybin to treat alcoholism. Some people have argued that perhaps the strongest evidence base for psychedelics is for LSD to treat alcohol dependence. There were a number of studies in the 60s, and some of their design wasn’t that bad. Outcome measures were improving. And with alcoholism, you have a more concrete measurement. A meta-analysis of the old research was carried out quite recently, and they looked at those studies which had the most rigorous methodology, and they found that the better-designed studies were showing good efficacy, comparable to the leading treatments today.

When did research start again in the UK?

I went to see David Nutt [former UK government drugs advisor] in 2004 / 2005. I was finishing my masters in psychoanalysis at Brunel, and wanted to do a PhD. I found a flyer on consciousness research, and contacted somebody who told me about David Nutt and Amanda Fielding at the Beckley Foundation. So I went to see both, and told them that my dream was to do a brain imaging study of LSD, and my hypothesis was that the psychedelic experience is like a REM experience, so you’re dreaming while awake. David said you have to walk before you can run – I didn’t have any experience in neuroscience at that stage – and I ended up doing a PhD on something vaguely related: MDMA, sleep and serotonin.

I still had these ambitions to do a brain imaging study about LSD. Amanda Fielding shared them – she runs a charity that does drug policy work and consciousness research, and after I’d finished my PhD, David said she had money to pay for a brain imaging study of psychedelics. At that point I designed the study of the effects of psilocybin.

Was that the first psychedelic research in the UK for a long time?

Yes it was. I don’t think there had ever been a published study on psilocybin in the UK.

How strange that no one else did a study in all that time.

Yes, it’s tricky to do.

Professor David Nutt of Imperial College

Why were you able to do it?

Because a number of critical ingredients came together, like David Nutt, an established pharmacologist at the top of the tree; and an independent philanthropist funder, because mainstream funders wouldn’t fund it; and then I guess a young researcher who had the energy.

Tell me about the study.

We gave psilocybin intravenously to people, so the effects are almost instantaneous and will last 45 minutes, rather than five hours. Rick Strassman referred to such trips as a ‘businessman’s trip’. Then we did an fMRI scan of their brains. And that’s when we saw a decrease in blood flow to certain parts of the brain. That was a bit of a revelation, as no one had ever shown that before. Some people had shown the opposite. So it was a bit of a head scratcher. We spent a good duration of time checking our results. But then we replicated what we found using a different modality – again an fMRI measure – and we again found drops in the fMRI signal after we infused the drug, in a particular area.

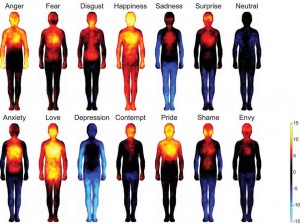

The decreases were in regions of the brain that have very dense connections – they’re like hubs in the network, centres of high interconnectivity. It was these regions that were showing the largest decreases. That got us thinking, when you have decreases in centres of information-integration, what happens to the system. The natural inference was, you’d have a more chaotic system that operates in a less organized and constrained way.

Do you see similar kind of activity during REM sleep?

Make room for the mushrooms

You see decreased blood-flow in association cortices at least posteriorly, so yes, you seem some correlation. So it’s possible that if these association regions have a constraining influence on other regions in the brain, that you may take the lid off the system and cause some dis-inhibition in other areas. In fact, that’s one of our most recent findings – there are regions that show elevated or at least more erratic activity after psilocybin. And the regions that show the increase in signal amplitude are particular subcortical regions like the hippocampus. And in REM sleep, brain imaging has also found increased activity in the hippocampus and the limbic region.

Which are more associated with memory and emotion?

Yes, exactly.

What’s your hypothesis of what’s happening?

It brings me back full circle to the Freudian model. It’s no coincidence that one of the most common descriptions you associate with psychedelic experience is ego disintegration. When people talk about ego disintegration, it isn’t cliquey Freudians smoking their cigars, it’s psychonaut kids.

The brain-scans from Robin’s study

So what does that mean at a physical and biological level? The networks that are the strongest candidates for the sense of self and the personality are precisely those that are ‘knocked out’, for want of a better word, under psychedelics. The puzzle is starting to fit quite neatly in my mind. If you’re decreasing the function in this particular network, then I offer the explanation that it’s a correlate of ego disintegration. In a further study using MEG – which measures brain waves – when we looked in one of the regions that showed the marked decrease in oscillatory power, its magnitude correlated positively with a subjective rating scale of ego disintegration (people were asked ‘Did you experience ego disintegration?’ and people answered on a scale from ‘not at all’ to ‘very much’.) Those who rated that very highly also had the biggest decreases in oscillatory power in this region which is part of the self network – the posterior cingulate cortex.

The unconscious that people seem to discover through psychedelic experience – is it closer to the Jungian unconscious than the Freudian model? People don’t seem to go into a savage Freudian jungle where they have sex with their mother and kill their father. It seems more like the Jungian wonderland – a more positive model of the unconscious, where people encounter not just dissolution and monsters, but some bigger cosmic Self.

Is the unconscious revealed by psychedelics more Freudian or Jungian?

I agree. Freud’s great merit was his mechanistic approach, he talks about systems – the ego system and the unconscious or id system. However, when he came to describe the quality of what the unconscious is, what you see under psychedelics isn’t really that, as you say it’s more consistent with Jung’s description of the unconscious. It’s tricky, because potentially at low doses, it may be more subtle, interpersonal insights and one’s self and relationships, whereas when the dose is higher, things might start becoming more archetypal, and be more about the history of the human animal.

What are the effects of psychedelics on memory? Freud suggested (like Wordsworth or De Quincey) that we never fully forget anything, experiences are always there in the unconscious. Do psychedelics unlock those memories?

You’ll find this in the literature – there are reports of vivid recollection. You sometimes see age regressions, people go back to being a child. Or they go back to what Stanislav Grof called ‘systems of condensed experience’ – experiences of particular salience and personal importance that the mind will go back to, and which you can sometimes re-live. This tends to happen spontaneously. It may happen when the drug is given orally rather than intravenously. A tricky issue is that when you give psychedelics, people seem to become hyper-suggestible. So there’s the question of whether this spontaneously occurs or if it’s being suggested to them.

Can psychedelic experiences be healing for people, and if so how?

Psychedelic experiences may be able to loosen very fixed negative schemas, or world-views

Yes. There are a couple of different models. There is an idea that psychedelics can allow personal insights – if one has a disorder or some symptoms of depression or anxiety, you might experience facilitated insight into the causes of these symptoms. That’s the classic idea of psychedelics to assist psychoanalytic therapy. Other models are more pragmatic – if, under the drugs, you induce a plastic state where people are hyper-suggestible, you might have a window of opportunity where you can address fixed behaviours which probably rest on fixed connections in the brain. For instance, with depression you might have a patient who is stubbornly pessimistic. What if you give them a psychedelic drug where all of a sudden you allow them to think differently and more fluidly. You might be able to start working with their cognitive biases and to get them to question their fixed schema about who they are.

Can you do that sort of CBT approach while someone is tripping?

I don’t think you could do it while someone is in the throes of a profound hallucinogenic experience. But it does loosen people up. What Roland Griffiths says is that often the most important work happens after the experience – it increases openness to new associations.

To what extent do people have spiritual experiences on psychedelics?

The literature is rich in reports of spiritual experiences. In our own work with psilocybin, we haven’t seen it to an impressive extent, maybe because the experience is short-lived, maybe because it’s not our participants’ first time tripping, so it perhaps is less new and revelatory.

You get people like Terrence McKenna who suggest you’re not encountering something within, but also something ‘out there’ – spirits, God etc. I’m interested if people are encountering similar things out there.

Alien visions could be a memory of the mother from infancy

Well, there is the collective unconscious, so if they experience similar entities, it might be appealing to a collective aspect of the unconscious which is about entity. Maybe it has a maternal presence. Also the wide eyes that people report around extra-terrestrials – Jung wrote about this, and suggested it might be related to memories of the mother looking down with big eyes. I find that appealing. For a materialist scientist, I don’t believe the theory that people gain access to a metaphysical or spiritual realm, I think what they have access to is the vastness of the human mind, which includes their entire history – which isn’t just human. It’s very easy to become less than objective, to believe that things are really happening, that the walls are breathing…but they’re not.

Still, I wonder if the beauty and healing of those experiences change one’s view of the unconscious – if you open up and let go of control, it can be a positive experience.

That’s probably true. My view of human nature has been changed not just through my limited research but through reading the psychedelic literature. But one thing I would say – when Freud wrote about the unconscious, one thing he emphasized is there’s no right and wrong in the unconscious. That’s why people get the ability to experience contradictory things simultaneously, like heaven and hell.

Have there been any studies of people tripping together?

Yes, I think so, in the fifties. I’d be skeptical of that sort of work, way too many confounds.

Usually people do it collectively – I’m just thinking of the setting of studies now, people on their own in hospitals.

It’s an interesting thought, it’s difficult to know what you’d infer. I recall a study where people are not talking, they’re looking each other, trying to communicate telepathically. And post-experience, they compared notes, and found they weren’t thinking about the same thing at all.

Yes, exactly, it would be interesting to test out whether people’s feeling that their minds somehow get entangled or extended is really true. But I guess mixing psychedelic research with paranormal research might be a step too far for most funders!

There are a lot of people interested in psychedelics within the research realm who are interested in that. They’ll tell you they’re skeptics, but I know they’d be very happy to find evidence of that. Of course, it would be a momentous discovery. My concern is that there’s a very strong potential for a bias around the fact that we get excited by the prospect of a complete paradigm shift. It’s a very seductive possibility, and it can cloud reason.

So it’s still difficult to get government approval for psychedelic research. What would you like to see changed?

It would be nice if they based their policy decisions on scientific evidence, and if they gave that primary consideration rather than secondary. Now they try and fit scientific data into their policies. Also it seems as though it’s relatively unproblematic to have these drugs as Schedule 1 – the idea is that shouldn’t affect research. You need a Home Office license to store and administer these drugs. The reality is these licenses are very expensive. Funders aren’t willing to pay for it. And they take a long time to set up – over a year. And there are more and more controls on the license. Things that should be relatively easy, like transferring a drug from one centre that has a license to another centre that has a license, are incredibly difficult. It’s harming the research. If this is a particularly exciting area of research, with huge potential, then these bureaucratic burdens will hold us back and handicap us.

And what, in a nutshell, is the potential?

To discover exciting things about consciousness and the brain, and to explore a truly novel therapeutic approach.

To discover exciting things about consciousness and the brain, and to explore a truly novel therapeutic approach.

So do you think there could be psychedelic treatments of things like depression and alcoholism?

If the evidence supports it, it would be unethical not to pursue them.

There was a recent meta-study suggesting there are no harmful impacts from psychedelics. Do you really think that’s true? It doesn’t seem to be in my experience and among my friends.

I’d have to read the paper. I think it’s the same team that did the meta-analysis on LSD and alcoholism. Other meta-analysis which have looked at the potential for harm, and also surveys we’ve run, and also meta-analysis of modern research, suggests that these drugs are certainly not without potential risks. However, the risks of adverse effects are relatively small, especially compared with other drugs. It’s a tricky one, which is difficult to summarise. There are certainly potential harms.

If we think they are dissolving the ego…

You have to ask why the ego is there at all.

And if people resist that dissolution, that might freak people out.

Exactly. That may be what ‘freaking out’ is – if people hold on to their ego while it’s dissolving, that could feel like dying.

I had never visited the graves of my own grandparents, people I knew and loved very deeply, yet felt compelled to walk the streets that my northern heroes had strode down and contemplate at their graves, my sonic pilgrimage always scored by the appropriate record.

I had never visited the graves of my own grandparents, people I knew and loved very deeply, yet felt compelled to walk the streets that my northern heroes had strode down and contemplate at their graves, my sonic pilgrimage always scored by the appropriate record.