Hannah Newton is a historian of early modern medicine, emotion, and childhood. Her first book, The Sick Child in Early Modern England (2012), won the EAHMH 2015 Book Prize. In 2011-2014, Hannah undertook a Wellcome Fellowship at Cambridge, and researched her next monograph, Misery to Mirth: Recovery from Illness in Early Modern England (forthcoming). She is now a Wellcome University Lecturer at Reading.

emotion, and childhood. Her first book, The Sick Child in Early Modern England (2012), won the EAHMH 2015 Book Prize. In 2011-2014, Hannah undertook a Wellcome Fellowship at Cambridge, and researched her next monograph, Misery to Mirth: Recovery from Illness in Early Modern England (forthcoming). She is now a Wellcome University Lecturer at Reading.

Why is the sound of sniffing so irritating? As I write this, my attention is drawn to the unremitting snorts and splutters of a fellow passenger on the train. It seems that I’m not alone: in one recent survey, sniffing was ranked one the top 20 most annoying noises by Britons.[1] But perhaps we’re overreacting. After all, sickness can give rise to far worse sounds, as I’ve begun to realise since embarking on a new Wellcome Trust project, ‘Sensing Sickness in Early Modern England’. Taking the dual perspectives of patients and their loved ones, the project investigates how the five senses were affected by serious physical illness and medical treatment, and uncovers the sights, sounds, smells, tastes and tactile sensations of the seventeenth-century sickroom. My ultimate goal is to reach a closer understanding of it was like to be ill, or to witness the illness of others, in the past. I also seek to unravel the relationship between the senses and the emotions in early modern culture. While historians have undertaken valuable work on how the senses were involved in theories of disease causation, diagnosis, and treatment, the sensory experience of illness itself has been largely overlooked.[2]

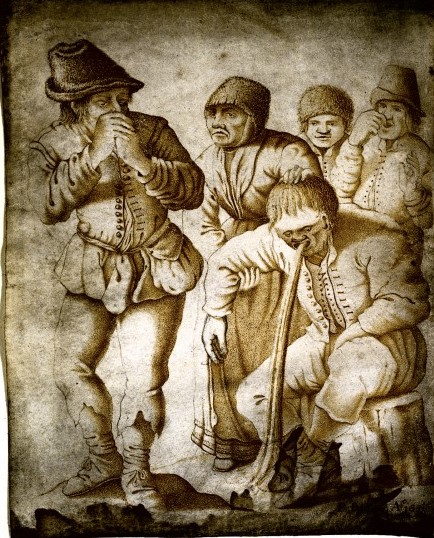

Figure 1: ‘The Sense of Smell’, 1651; by P. Boone; Wellcome Library, London. A man vomits, while those around him hold their noses. It is noteworthy that the only female in the image – possibly a nurse – is not holding her nose. Could this be because the artist assumed that women’s work desensitised them to bad smells? This image could equally have been used to illustrate the sense of hearing or vision.

I became interested in this subject whilst researching for a previous book, The Sick Child in Early Modern England. I noticed that for parents, the greatest source of grief was not so much the death of a child, but was rather hearing and seeing their offspring in pain. During the sickness of his baby daughter Mary in 1669, the Suffolk clergyman Isaac Archer (1641-1700) lamented, ‘Oh what griefe was it to mee to heare it groane, to see it’s sprightly eyes turne to mee for helpe in vaine!’[3] In fact, so acute was the distress occasioned by these sensory stimuli, parents frequently claimed to feel something alike to the emotional and physical suffering of their sick children. This phenomenon was known as ‘fellow-feeling’ in the early modern period, a concept which meant ‘to partake in another person’s occasions, either of joy or sorrow’. Explanations for fellow-feeling centred on the emotion of love. The French philosopher and theologian Nicholas Coeffeteau (1574-1623) averred that a ‘signe of true Love…[is that] friends rejoice & grieve for the same things’.[4]

What were the sounds of the sickroom? The diary of the newly married gentlewoman, Mary Penington (c.1623-1682), provides poignant insights. She recorded that the groans of her sick husband ‘were dreadful. I may call them roarings’. Forty years later, she still remembered his groans, and added another auditory memory: the sound of his convulsing limbs as they slammed against the bed in his fits:

[H]e snapped his legs and arms with such force, that the veins seemed to sound like the snapping of cat-gut strings, tightened upon an instrument of music. Oh! this was a dreadful…sound to me; my very heartstrings seemed ready to break, and let my heart fall from its wonted place.[5]

By applying the metaphor of breaking strings to both her own emotions and her husband’s fits, Mary conveyed the depth of her fellow-feeling – her heart was mimicking his experience. To explain the emotional impact of sound, contemporaries referred to the link between the ear and the heart. The priest Thomas Wright (d. 1624), explained that the ‘shaking, crispling or tickling of the air’ – what we would call sound waves – ‘paseth thorow’ the body ‘unto the heart, and there beateth and tickleth it in such a sort, as it is moved with semblable passions’.[6] Personified as a sensitive creature, the heart generated passions that resembled the movement of the vibrations it perceived, which in Mary’s case was violent grief. It seems fitting that the words ‘hear’ and ‘ear’ are contained within ‘heart’.

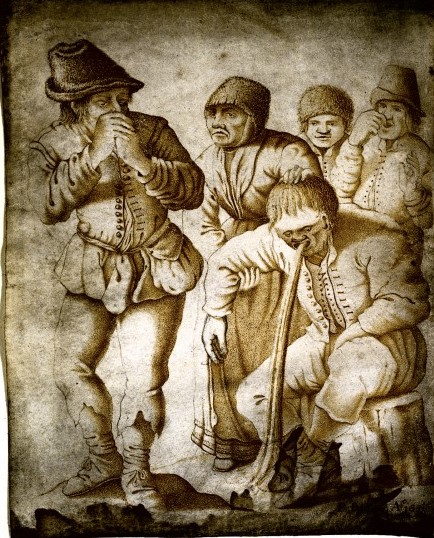

Figure 2: ‘The Bitter Potion’, 1640; by Adriaen Brouwer; Städel Museum, Germany. The man’s face is contorted in an expression of deep revulsion after tasting the bitter medicine. In this period, bitterness was a sign of the drug’s potency.

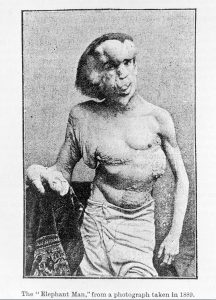

Sights as well as sounds contributed to the agony of witnessing a loved one’s illness. One of the most heartrending sights was the facial expression of the sick person, typically grimaced in pain, or contorted through crying.[7] Timothy Bright (1551?-1615), a physician from Sheffield, provides a vivid picture of the ‘deformitie of the face in weeping’ in his treatise on melancholy. He wrote, ‘The lip trembleth’, the ‘countenance is cast downe’, and ‘all the parts [are so] filled with…moisture…that not finding sufficient way [out] at the eyes, it passeth through the nose’.[8] Relatives commented particularly on the look in the patient’s eyes, a tendency which reflects the entrenched belief that the eyes were the windows of the soul.[9] A poem composed by the Devonshire gentlewoman Mary Chudleigh (c.1656-1710), concerning her gravely ill daughter, Eliza Maria, encapsulates this experience:

Rack’d by Convulsive Pains she meekly lies,

And gazes on me with imploring Eyes,

With Eyes which beg Relief, but all in vain,

I see, but cannot, cannot ease her Pain.[10]

This mother’s inability to relieve her child’s sufferings accentuated her distress. Sight functioned in this context in a cyclical manner: the agony conveyed in the patient’s eyes pained the observer, and the observer’s pained expression added further grief to the patient. Relatives also mourned the loss of their loved one’s natural beauty and colour. Addressing the friends and relations of the sick, the London clergyman Timothy Rogers, asked ‘Where is his former Comeliness and Beauty…his lovely Features? You can…have no mind to look upon that very person that…a while ago, was the Delight of your Heart’.[11]

To conclude, witnessing the illness of a loved one was a deeply sensory experience in the early modern period. For those involved in the care of a sick or elderly relative, it may still be today. This blog has focused on just a few of the most frequently mentioned sights and sounds; my wider project also examines the smells, tastes, and tactile sensations that accompanied disease and treatment.

[1] http://www.mirror.co.uk/news/weird-news/britains-top-50-most-annoying-8826311 (accessed 10/01/17)

[2] For example, William Bynum and R. Porter (eds), Medicine and the Five Senses (Cambridge, 1993), explore the role of the physicians’ senses in diagnosis. On the contested role of touch in diagnosis, see Olivia Weisser, ‘Boils, Pushes and Wheals: Reading Bumps on the Body in Early Modern England’, SHM, 22 (2009), 321-39; Patrick Singy, ‘Medicine and the Senses: The Perception of Essences’, in Anne Vila (ed.), A Cultural History of the Senses in the Age of Enlightenment (2014), 133-53. On the role of bad smells in causing disease, see Jonathan Reinarz, Past Scents: Historical Perspectives on Smell (Illinois, 2014), ch. 6; Holly Dugan, The Ephemeral History of Perfume: Scent and Sense in Early Modern England (Baltimore, 2011), 97-125. On the role of scents in healing, see Jennifer Evans, ‘Female Barrenness, Bodily Access and Aromatic Treatments in Seventeenth-Century England’, Historical Research, 86 (2014), 423-43. On the benefits of pleasant smells and sights, see Carole Rawcliffe, ‘“Delectable Sightes and Fragrant Smelles”: Gardens and Health in Late Medieval and Early Modern England’, Garden History, 36 (2008), 3-21. On the role of sound (music) as therapy, see Peregrine Horden (ed.), Music as Medicine: The History of Music Therapy Since Antiquity (Aldershot, 2000).

[3] Isaac Archer, ‘The Diary of Isaac Archer 1641-1700’, in Matthew J. Storey (ed.), Two East Anglian Diaries 1641-1729, Suffolk Record Society, vol. 36 (Woodbridge, 1994), 41-200, at 120.

[4] Nicolas Coeffeteau, A table of humane passions. With their causes and effects (1621), 111-12, 117-19.

[5] Mary Penington, Experiences in the Life of Mary Penington Written by Herself, ed. Norman Penney (London, 1992, first publ. 1911), 70-71, 93.

[6] Thomas Wright, The passions of the minde (1630; first published 1601), 169-70.

[7] On facial grimaces, but for a later period, see Joanna Bourke, The Story of Pain: From Prayer to Painkillers (Oxford, 2014), ch.6.

[8] Timothy Bright, treatise of melancholie (1586), 153-54.

[9] Stuart Clark, Vanities of the Eye: Vision in Early Modern European Culture (Oxford, 2007), 11.

[10] Mary Chudleigh, ‘On the death of my dear daughter Eliza Maria Chudleigh’, in her Poems on several occasions (1713), 95.

[11] Timothy Rogers, Practical discourses on sickness & recovery (1691), 228-29.

Tell me about the new book, The Roots of Yoga.

Tell me about the new book, The Roots of Yoga.