Paul Megna is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow with the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions, based at The University of Western Australia. He is currently developing a project on emotion and ethics in medieval and medievalist drama. He was awarded a PhD in English by the University of California, Santa Barbara, for his dissertation titled ‘Emotional Ethics in Middle English Literature’.

Paul Megna is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow with the Australian Research Council Centre of Excellence for the History of Emotions, based at The University of Western Australia. He is currently developing a project on emotion and ethics in medieval and medievalist drama. He was awarded a PhD in English by the University of California, Santa Barbara, for his dissertation titled ‘Emotional Ethics in Middle English Literature’.

This is the latest in a series of posts about anger, and a second response to Thomas Dixon’s post ‘Angers past or anger’s past?’ The first response was by Kirk Essary. All three posts have also appeared on the ARC Histories of Emotion Blog.

In his recent post, Thomas Dixon argues that historians of emotion should avoid too readily conflating our contemporary understanding of anger with those espoused by the denizens of the past societies that we study. This is, of course, a crucial point and to argue against it would not only pay short shrift to the very real linguistic, phenomenological and ethical distinctions between our anger (or, since there are important differences between the ways that contemporary English-speakers conceive of anger, our angers) and angers past, but would also downplay the important cultural work of studying the history of anger in the first place. Nevertheless, I worry that too much focus on the divergence between our post-Darwin, post-Ekman understanding of anger and that of, say, Geoffrey Chaucer runs the risk of ignoring the equally important ways that angers past remain recognisable to us today.

Take, for example, a hilarious (at least in my humble opinion) moment in Chaucer’s Summoner’s Tale.[1] A greedy, sanctimonious friar is visiting his long-time patron Thomas, who lies on his deathbed. Thomas is angry with the friar since he has given ‘many a pound’ (III.1950–51) to friars, but never seems to fare better for his donations. After the Friar delivers a long, condemnatory sermon on the evils of wrath, Thomas becomes still angrier, but conceals his indignation and offers to give the friar yet another gift, as long as he agrees to split it amongst all of his brothers. Thomas instructs the friar to reach beneath his buttocks and, when the latter obeys, Thomas farts more loudly than any horse ever did, leaving the friar insane with anger, cursing Thomas through clenched teeth. My point is simple: modern readers both understand the friar’s anger and ‘get’ the Summoner’s joke. Even if we are totally unaware that friars were often lampooned in Chaucer’s time for spreading rage by usurping the sacramental business of local parsons, we grasp why the friar is angry because we would also probably be angry if we, upon being offered a gift, received instead a handful of farts. I daresay Thomas’s trick might enrage even the stoic Inuit Kigeak, Jean L. Brigg’s adopted father, discussed in another recent post by Thomas Dixon. Taken out of context, Thomas’s trick is not necessarily funny (it would not be funny if it happened to Kigeak), but I am able to laugh at the Summoner’s friar’s angry reaction to the trick because it proves him a hypocrite for preaching against the evils of anger. Despite arising from a radically different cultural milieu than my own, Chaucer’s depictions of anger and solicitations of laughter translate well, to borrow a phrase from Maxine Hong Kingston.[2] If they did not, I might have chosen a very different career path.

Figure 1: The Summoner in the Ellesmere manuscript of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

As Dixon points out, medieval Europeans strongly associated anger with the mortal sin of wrath. Medieval discourses on wrath, however, rarely conflate anger and sin entirely and often explicitly demarcate sinful anger from righteous anger. Elsewhere in Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, in The Parson’s Tale,[3] we get a thoroughgoing definition of sinful wrath, as well as its remedial virtues. Although the Parson does not prescribe righteous anger as the remedy for sinful anger, he does introduce his discussion of sinful wrath by positing that not all anger is sinful: ‘Ire is in two maneres; that oon of hem is good, and that oother is wikked’ (X.537). Good ire, for the Parson, is ‘withouten bitternesse’ and directed at ‘wikkednesse’, rather than the purveyor thereof (X.538–40). Supporting his discussion of righteous anger, the Parson cites Psalms 4.4 (the translation history of which Kirk Essary discusses in his recent post): ‘Irascimini et nolite peccare’ (‘Be angry and don’t sin’). In discussing sinful anger, the Parson introduces another split, this time between sudden or hasty ire, which occurs ‘withouten [. . .] consentynge of resoun’ and is therefore a venial sin, and ‘wikked’ anger, to which reason consents, making it a mortal sin (X.540–42). Once again, the finer points of Chaucerian anger are caught up in a sacramental theology that is quite foreign to some, though certainly not all, modern readers. As Thomas Dixon puts it, ‘[t]here is a substantive difference – phenomenologically and emotionally, morally and metaphysically – between committing the deadly sin ira and expressing the modern emotion of “anger” as conceived by a psychologist like Paul Ekman’.

On the other hand, the Parson’s discourse on anger is not so different, I think, than that expressed in Martha Nussbaum’s new book,[4] which Dixon aptly summarises in yet another previous post. Nussbaum is characteristically not content with being merely descriptive (as is Ekman’s psychology of anger), but is also prescriptive insofar as she hopes to provide us a blueprint for building a better society by instituting a healthier, neo-Stoic emotional regime. Her project, therefore, is not so unlike that of Chaucer’s Parson. Although I would certainly stop short of conflating the two prescriptive philosophies of anger entirely, I do want to point out that Nussbaum, like the Parson, disapproves of almost all anger, especially insofar as it entails a desire for revenge, but she does leave room for a healthy, acceptable ‘transition anger’, as long as it fuels efforts for preventative reform. Nussbaum’s ‘transition anger’ strikes me as existing somewhere between the Parson’s righteous anger and his venial, hasty anger. Despite their very real differences, the discourses on anger offered by Nussbaum and the Parson contain an uncannily similar ascetic program for producing a better world by emoting well. Both are forgiving of impulsive anger and critical of seething anger that broods on vengeance.

I certainly do not mean to suggest that it is easy to reconcile medieval and modern discourses on anger. Dixon alludes to the work of linguists like Anna Wierzbicka who analyse the various semantic valences of Old and Middle English anger-words, none of which coincide entirely with that of the Modern English ‘anger’. Inherited from Old Norse, the Middle English anger, for example, can signify something roughly akin to our anger, but, like the Old Norse angr, might also mean a much more general sense of sorrow or displeasure.[5] Making matters worse, in a time before authoritative dictionaries, words were used differently by different folks (as they continue to be today, despite a plethora of dictionaries!) Chaucer, for example, uses ‘ire’, ‘anger’, and ‘wrath’ more or less interchangeably, relying heavily on adjectives to signify the moral status of the anger in question. While some taxonomically minded Middle English authors, like Reginald Pecock,[6] explicitly distinguish between ‘anger’ and ‘wrath’, making the former a passion over which one has no control and the latter a wilful, and therefore potentially sinful, deed, such careful semantic distinctions between anger-words are the exception, rather than the rule, in Middle English anger writing.

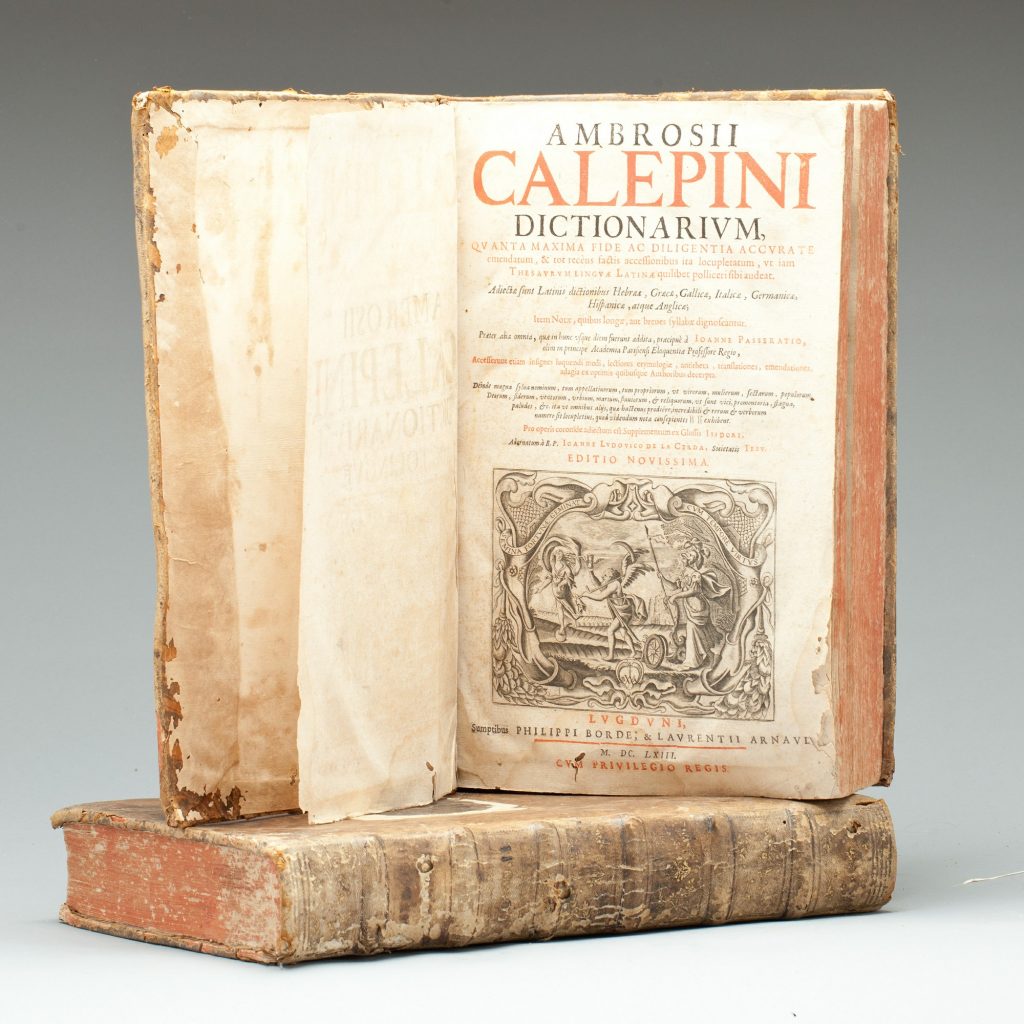

Figure 2: ‘The Death of Wat Tyler’, in Jean Froissart, Chroniques, late fifteenth century. British Library, Royal MS 18 E I, f.175.

Making matters still more difficult for those of us interested in reconstructing medieval notions of anger is the fact that all we have to understand them is surviving texts, works of art and archaeological remains. As many historians have noted, this yields an uneven record, skewed towards those possessing the privilege to produce: churchmen, aristocrats and poetic social climbers like Chaucer and John Gower. This poses a distinct problem for those interested in peasant anger: we have a glut of sources depicting peasant anger as bestial and socially disruptive – like Book I of Gower’s Vox Clamantis – and a dearth of sources indicating how peasants conceptualised anger differently than their oppressors. [7] Despite this difficulty, historians and literary critics like Paul Freedman and Steven Justice have done a great deal to study medieval peasant anger, sometimes by reading aristocratic chronicles against the grain and sometimes by focusing on small scraps of peasant discourse preserved in hostile sources.[8] I’m thinking, of course, of Justice’s fantastic work on the Rebel Letters: Middle English lyrics which served as peasant communiqués contained in otherwise Latin chronicle accounts of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381.[9] In an article published a few years ago,[10] I argued that one of these short lyrics tells us a great deal about peasant anger without using a single anger-word. The lyric in question is called ‘The Letter of John Ball’ and is attributed to the radical priest of that name who rallied the Rebels at Blackheath with a rousing, proto-Marxist sermon. It derives from a common complaint lyric that bewails a world in which the Seven Deadly Sins run rampant:

Now raigneth pride in price,

Covetise is holden wise,

Leacherie without shame,

Gluttonye without blame:

Envie raigneth with treason,

And slouth is taken in greate season;

God doe bote, for now is time.

Unlike its sources and analogues, the ‘Letter of John Ball’ does not complain that the world is replete with wrath. In leaving anger conspicuously absent, Ball’s complaint implies that wrath is not a cause of the social inequality against which Ball preached, but a solution to it. The implicit endorsement of righteous anger contained in the ‘Letter of John Ball’ suggests that not all medieval laypeople adhered to the narrow understanding of righteous anger espoused by their confessors and that some recognised discourses on the deadly sin wrath as mechanisms designed to dissuade dissent. Sadly, the paroxysm of anger expressed in the 1381 Rising led to a draconian crackdown on peasant rights spearheaded by a young and preternaturally angry King Richard II. Nevertheless, John Ball and his compatriots Wat Tyler and Jack Straw continue to reside in the English proletariat imaginary as powerful symbols of righteous anger and dissent.

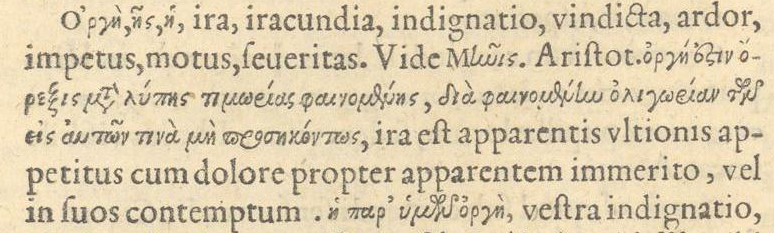

Figure 3: Frontispiece and first page of an early edition of William Morris’s A Dream of John Ball (London: Kelmscott P, 1892). Artwork by E. Burne-Jones, April 1888. Newcastle University Library, Special Collections, RB 821.86 MOR.

In 1888, 507 years after John Ball was hanged, drawn and quartered for rousing rebel anger, the socialist reformer William Morris published a short serialised novel entitled A Dream of John Ball, which details a dream vision in which the protagonist, a nineteenth-century socialist lecturer, finds himself in fourteenth-century England. Morris’s dreamer meets a peasant rebel and recites snippets of a Rebel Letter to showcase his socialist sympathies. He then hears Ball give a radical sermon and witnesses a minor skirmish early in the Revolt. In the story’s concluding chapters, he conducts a long, private conversation with Ball in which he details the sad results of the Revolt, the end of feudalism, the industrial revolution and the rise of a capitalist mode of production that leaves the working class infinitely more disenfranchised than medieval peasants. Needless to say, Ball is not thrilled by what he hears. At one point, he even furrows his brow in anger. Although Morris’s nostalgic novel provides a markedly pessimistic counterpoint to the neo-medieval utopia imagined in News from Nowhere, A Dream of John Ball hints at a dream of a utopian future shared by Ball, Morris’s protagonist and modern readers of historical records of class struggle such as myself. Morris places John Ball’s peasant anger in dialogue with that experienced by the proletariat under industrial capitalism. In so doing, he allegorises the way that historical inquiry fosters connections between past and present political emotions. Just as Morris resuscitates Ball’s anger, so do the historians of emotion who study peasant anger to build an archive of class struggle.

Do I mean the exact same thing when I say ‘wrath’ as did John Ball when he said it, or strategically opted to not say it, more than 700 years ago? Of course not. I can neither fully grasp peasant anger, nor Morris’s socialist discontent, nor the anger felt by African Americans, many of whom feel persecuted and endangered by the justice system that is ostensibly supposed to protect and serve them. But the unknowability of other people’s anger, historical or contemporary, does not absolve me of responsibility to empathise with it and even partake in it, to the extent that I can or choose to. As historians of emotion, we need to both respect and transverse historical difference. We need to study the roots and analogues, not only of anger that we deem righteous, but also that which we deem toxic (or Trump-esque), in order to help others and ourselves manage and understand contemporary anger. Our task, therefore, is not so different than that undertaken by either Nussbaum or Chaucer’s Parson. Somewhere between descriptive and prescriptive lies the vital work of the historian of anger.

[1] Geoffrey Chaucer, The Summoner’s Tale, in The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry D. Benson, 3rd edn (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1987), pp. 129–36.

[2] Maxine Hong Kingston, The Woman Warrior: Memoirs of a Girlhood Among Ghosts (New York: Vintage Books, 1989).

[3] Geoffrey Chaucer, The Parson’s Tale, in The Riverside Chaucer, ed. Larry D. Benson, 3rd edn (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1987), pp. 287–327.

[4] Martha Nussbaum, Anger and Forgiveness: Resentment, Generosity, Justice (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016).

[5] I am grateful to Carolyne Larrington for helping me to trace anger’s transition from Old Norse to English.

[6] Reginald Pecock, The Folewer to the Donet, ed. by E. V. Hitchcock (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1924), p. 110.

[7] John Gower, Vox Clamantis, in The Complete Works of John Gower: Latin Works (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1902), pp. 3–313.

[8] See, for example, Paul Freedman, ‘Peasant Anger in the Late Middle Ages’, in Anger’s Past: The Social Uses of an Emotion in the Late Middle Ages, ed. by Barbara H. Rosenwein (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1998), pp. 171–88.

[9] Steven Justice, Writing and Rebellion: England in 1381 (Berkeley: The University of California Press, 1994).

[10] Paul Megna, ‘Langland’s Wrath: Righteous Anger Management in The Vision of Piers Plowman’, Exemplaria 25.2 (2013): 130–51.

Paul Megna

Paul Megna

![Sol Eytinge, ‘Dora and Miss Mills’. Wood engraving from Dickens's David Copperfield in the Ticknor and Fields (Boston), 1867, Diamond Edition [Victorian Web].](https://emotionsblog.history.qmul.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/dora-and-miss-mills-225x300.jpg)